There is overbearing stigma around mental illness and many misconceptions surrounding it.

Suffering from mental illness often costs one their means of livelihood.

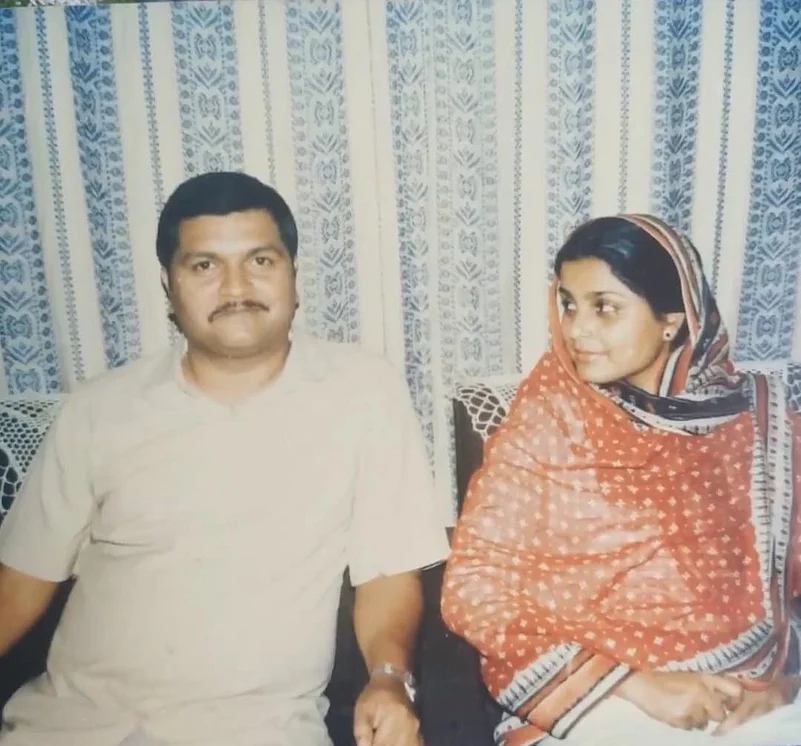

Living with a partner who has mental health issues involves life-long struggle and immense personal sacrifice.

Bright fluorescent light flooded the otherwise dingy room from every corner. It looked like a prison cell, not least because of its grilled gate and armed guards. A low hum of listless chatter filled the air, with occasional yelling. My mother had gone to talk to the psychiatrist about my father’s recovery. He seemed a little better, more himself than he had been lately. But there was still a long way to go. We were visiting him after some time and I was left to spend a few minutes with him. While he was away for a moment to use the washroom, one of the patients came up to me. I was naturally a little concerned, as I saw no one familiar around. He handed me a chit with a phone number in it. Looking over his shoulder, he whispered, “Please call them when you leave from here. They will come to take me. These people won’t let me go otherwise.” As my father returned, he quickly said, “Please don’t forget” and left. I showed the chit to my father. He said, “He’s crazy, forget it. His folks have left him here and gone.”

It must have been 2010 or 2011—it’s hard to remember; years of going in and out of hospitals and rehabilitation centres can do a number on your memory. I would later find out that there were many like this person in that psychiatric ward, who were paid for by their families, but never taken back. My father, however, was always confident that he would eventually be home. Whenever he was admitted to a hospital or a rehab for a prolonged period, the nursing assistants would always report about him asking the same question—“When can I go home?” If not anything else, that was perhaps the one certainty my mother had been able to instil in his fragile mind with her care.

My parents got married more than four decades ago. As quite a few arranged marriages go, much was left to find out after the deed was done. There was no conversation about his illness when the match was fixed. Some in his family knew that he had just been recovering from his first manic attack in 1982—he had threatened a fellow colleague with a knife during a tiff and contradicted a senior on being reprimanded. Consequently, he had to be admitted to the military hospital by force. But the overbearing stigma around mental illness and the common misconceptions surrounding it prevailed over good sense. Well-wishers in the know assumed that marriage and its entailing responsibilities will change the man, maybe cure him as well.

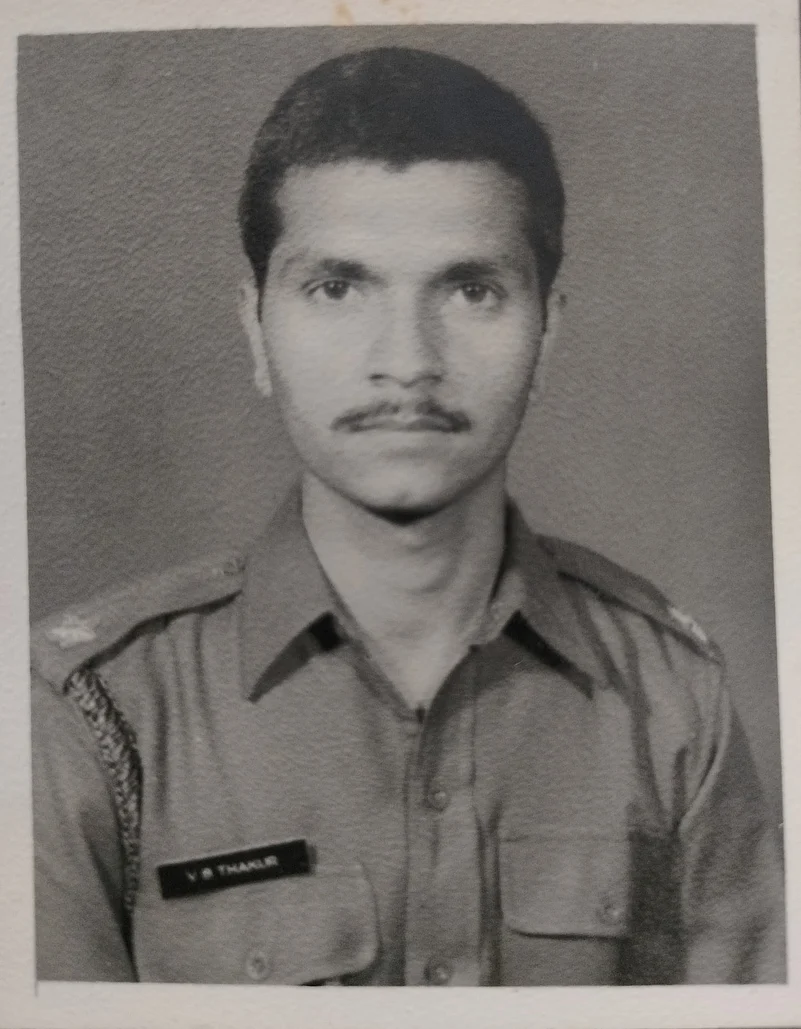

“On our first night together, he cried a lot,” my mother recalls. “He told me that he had been in a hostel since a very young age and didn’t harbour very strong bonds with his family.” My father was an officer in the Indian Army, where most interpersonal relationships are quite formal. There was little scope, therefore, to have close friends. “My first impression of the man was that he was quite lonely and introvert,” she says. “However, I don’t think I fully comprehended what he said to me—the illness itself, the technicalities within the Army that would arrest his promotion—it all seemed startling at first. Little did I know what would follow and how.”

His refusal to pay heed to the psychiatrist’s advice of continued medication led to my father having a second manic attack, just a few months later. Yet again, he was admitted to a hospital forcibly by some colleagues. Whenever the combination of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder—which he was diagnosed with—acted up, he would resist treatment as he believed he was absolutely fine. “In the early months of our marriage, we stayed apart a lot due to his postings. He wrote lengthy letters to me in his beautiful handwriting, telling me about his life in the Army and asking after my well-being,” my mother reminisces.

“However, when he was admitted for the second time, the letters that started coming in were much shorter, in terrible handwriting. Perhaps, it was the impact of psychiatric medication, which causes your hands to shiver a lot.” Nevertheless, the contents of the letters stated otherwise, which is why there was little to suspect. “When he came back home after admission for a few days, the sheer amount of medication he was taking worried me. The 20-year-old naive me wondered why he should have so many medicines, when they have such a harsh impact on him. So, I threw them away,” she says with some regret.

By the end of 1984, they had their first daughter. My mother accompanied him after a few months on his posting to Meerut, where he had finally been designated a family quarter. This was when the full blow of his illness hit her, as he went through his third manic attack. “The symptoms began when he had visited his village—sleeplessness, anger and unusual restlessness,” she says. “In Meerut, he would want to go visit the temple at 1 or 2 o’ clock in the night. When I’d refuse, he’d force me to stand under the shower and take me dripping to the temple, while the baby was left at home with her grandparents. I witnessed his illness unfold in a state of complete shock.” He was strongly suspicious of medicines being mixed in his food and water. “He would step out of home at odd hours. Upon returning, he would bang the door, waking all the neighbours up.” The final straw for her was seeing him come home seriously bruised one day, after he had met with a horrible road accident, while trying to drive in a sleepless state.

After consulting with a senior officer and finding out about his earlier admissions, my mother took the call of getting him admitted for the third time. But here was the catch—a third admission for psychiatric issues entails dismissal from the Army. “When the personnel came to take him, he hid in the bathroom. I was overwhelmed to see him like this, while nursing an infant in my arms.” When she met him after the admission, he lashed out against her decision. “What was the point? The other personnel want to trap me and stop my promotion. Do you not see this?” he asked her.

As the doctor called to inform my mother that my father would be invalidated from the Army for being mentally unstable, he gently nudged her to challenge the decision. “It’s true that such a verdict is rarely reversed and it has hardly ever been challenged. But there’s no harm in trying,” the psychiatrist had suggested. “This was perhaps one of the toughest points in my life. I was numb from what was happening to me. And there was hardly any support—in those days, telephones were still not readily available and somehow, my letters weren’t reaching my parents,” she recalls. Eventually, her parents arrived after a couple of months. Her father, especially, was filled with deep regret about not having verified the boy’s background at his workplace.

“Our attachment was not as deep yet, and I began imagining a life without him. I started thinking of ways to financially sustain myself and my child if he was dismissed from the Army.” Nevertheless, she took up the psychiatrist’s suggestion and decided to challenge my father’s invalidation, with the support of a lawyer. She was 22 at the time. “In our petition, we argued that he had been a part of the institution since childhood, having studied in Sainik school, then NDA and IMA. Therefore, the institution had to take some responsibility for his condition. We appealed that he be given sedentary duties, like many other officers who suffer from chronic ailments such as heart problems.” The whole process took 9-10 months, during which time he received just half his pay. “I became extremely particular about his timely medication. And slowly, he seemed to get better.”

Against all odds, my parents won the case. The authorities agreed to retain him and restore his job with sedentary duties, devoid of any decision-making power. When I ask her why she chose to stay and fight, even though she had considered leaving, she becomes emotional. “Maybe, the love was yet to arrive. But you can gauge a man’s personality from such proximity. I thought he was a gentle, caring and good human being. Perhaps somewhere, I was still unaware of how much more was left to witness. Perhaps, I had also been brought up to believe that this is what it means to be a good life partner.”

The journey that took off from this juncture during his period of service was a bumpy one. “He was unable to clear the exams for his promotion as he was unable to concentrate—a symptom of his illness,” she tells me. “Tests that were a breeze for others became insurmountable for him. The fear of him losing his job never left me. So, I’d sit down with him myself and read to him. Even so, he’d barely be able to sit still for half an hour at a time. Sometimes, he’d secretly doze off, while I read. And the next day, he remembered nothing.” He was unable to attend to simple chores designated by his superiors, so she took care of them for him.

The uncertainty of their future, and the future of their two children, drove my mother to pursue her B.Ed and then her M.A., while I was still a baby. “I had to have my options ready, in the event that he would be dismissed from his job without any retirement benefits,” she says. Often, during his hospitalisation, she had to leave her young children with her mother. “My heart broke at the thought of how my child must feel abandoned. But there seemed to be no other way back then,” she rues. As the promotions didn’t come through, my father lost motivation to keep pursuing his job. “It almost seemed like he didn’t want to work back then. He would find it difficult to keep up with basic tasks. Every day, he would talk about failing and trailing behind his peers, who had gone far ahead in their careers. And each day, it became my job to counsel him for hours on how far he had come in life.”

My mother had also wished to attempt civil service examinations. But given the circumstances, these wishes had to be set aside, to make way for more feasible professions like teaching. “When I look back at this time, however, I feel no regrets. Sustenance may have been a challenge, but my husband never stopped supporting me in my pursuits of higher education. He made sure that I understood how to go about at banks, deal with taxes and other such essential tasks—things that women in conventional households are never taught.” Even with regards to having children, she says that they had detailed discussions and she had full autonomy over her choices. She confesses that it was also the charm of Army life that kept her going. “I had a very protected life before my marriage. But the exposure and the freedom that the institution offered transformed me. That, alongside my husband’s guidance, made me my own person in many ways.”

“When I look back, I’m often startled by just how much I was doing at the same time. But back then, it seemed like the only way to exist”.

When the voluntary retirement came, however, the situation started heading south again. “My children were still in school when he retired, which is why I started working full time as a teacher,” she says. Initially, he attempted to work in civil companies. But it had become impossible to hold down any jobs. “Eventually, the stress in these jobs started getting to him. His restlessness began to resurface. The monthly psychiatric injection that he had hitherto been taking was insufficient. The suspicions appeared again, and they were mostly directed at me.” The psychiatrist she was consulting would give her soluble medicines to mix in his food. “But that made him drowsy, because in illness, he resisted sleep.” Consequently, it was recommended that he stop working altogether and rest at home.

For a while, this worked. But the period didn’t last long. Over the next few years, he would have manic phases more frequently—where he would have bouts of uncontrollable anger, turn violent, become suspicious and engage in irrational whims. In early 2010, when he was in an agitated frame of mind, the psychiatrist recommended that he be allowed to travel to his village, for a change of environment. However, during his journey by train along with his nephew, he got off at an unknown station while his nephew was asleep. He had no ID, no wallet and no cell phone on him. “I was at my wit’s end. I couldn’t comprehend what was happening,” my mother recalls. The next seven days were filled with horror and trepidation, as friends and family put together all their resources to trace him. “We didn’t know where to begin. But no stone was left unturned in the search—from media persons, to police officials; from government servants to ex-colleagues in the Army—there was no one who wasn’t looking for him.” Almost when we were giving up any hope of finding him, we’d received a call from an engine driver from Bhadrak, Odisha, telling us that he found him wandering on the station, with barely any clothes on. “He was hardly in his senses, but he remembered his own phone number. And that’s where the call came. The gentleman had been kind enough to admit him to a local hospital and requested us to come and get him.” My mother and sister travelled by road from Hyderabad to Bhadrak to get him back. When they found him, he was in a state of psychosis.

Therein began a journey in and out of hospitals and mental wellness centres, which only ended with his passing in February this year. “These years have passed in a haze. I only remember the immense exhaustion and frustration—his condition became a cyclical process. Every time he would get even remotely stable, he would fall into the same cycle again. It didn’t help that he had physical co-morbidities like diabetes and hypertension.” A concoction of medicines—both for his schizophrenia-bipolar combine as well as his physical ailments—started taking a severe toll on his body. On some occasions, he was under-medicated; on others, over-medication became near-fatal and he would have to be hospitalised for poisoning. In one clinic, he was administered electroconvulsive therapy without my mother’s awareness or consent. Eventually, his health became the centre of my mother’s world and ours. As his condition steadily deteriorated, the various combinations of medicines began to prove ineffective. Increasingly bed-ridden, he began to become fully dependent on my mother even for basic tasks like using the toilet or taking a bath.

“Throughout this time, I continued to work, because that was the only space where I could still feel like I was a person beyond nursing my partner.” In the last few years of his life, it seemed like my mother was living with an overgrown child—changing his diapers, cleaning his soiled clothes, feeding him, giving him medicines at the right hours, and sleeping by his side at night. But her body had started giving way, too. Even with a hired 12-hour caregiver, the task of caring for my father had become formidable. “When I look back, I’m often startled by just how much I was doing at the same time. I keep wondering where that capacity came from. But back then, it seemed like the only way to exist. It is like you are permanently in a state of emergency.”

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Often, she would break down from the stress of running from one hospital to another. The fact that mental health is not covered by any medical insurance, including the one offered by the Army to retired personnel, didn’t help either. “I had practically begun to lose myself in this process. It was because my elder daughter was by my side through a lot of this that I still had some grip over my own sanity. She would make it a point to take me to watch a film or for a performance once in a while, just so I could forget about home for some time.” During the last couple of years, my mother’s condition had begun to scare both me and my sister. Her memory had started failing her and she would frequently lose coherence while talking. Often, a conversation that began with talking about her, would eventually lead up to my father and his health. She treated him as an extension of herself.

My father passed away five months ago due to the compounded effects of his prolonged illness. It was sudden, but also a long time coming. With her retirement from teaching taking place around the same time, my mother has just begun rediscovering fully what she has been through on this tumultuous journey. In all these decades, our family battled social ostracisation, structural stigma and the healthcare system’s inability to deal with mental illnesses effectively. “On one hand, I witnessed his suffering more intimately than anyone else, almost as if it was my own. I knew that his body had seen enough. But on the other, I can’t help but continue to wonder, what if, he could have been with us a little bit longer?”

Apeksha Priyadarshini is Senior Assistant Editor, Outlook. She writes on cinema, art, politics, gender & social justice.

In its August 21 issue, Every Day I Pray For Love, Outlook collaborated with The Banyan India to take a hard look at the community and care provided to those with mental health disorders in India. From the inmates in mental health facilities across India—Ranchi to Lucknow—to the mental health impact of conflict journalism, to the chronic stress caused by the caste system, our reporters and columnists shed light on and questioned the stigma weighing down the vulnerable communities where mental health disorders are prevalent. This story appeared in print as Life, Together.