After a spate of BLO suicides, the Election Commission of India’s one-month deadline for its Special Intensive Revision (SIR) has come under scrutiny, as BLOs speak of “inhuman working conditions”.

Outlook spends a day with Booth Level Officers in Gautam Buddha Nagar to understand the daily pressures they endure.

This difficult experience is not unique to Gautam Buddha Nagar. From Noida to Patna, BLOs lament the financial, emotional, and physical toll exacted by this month-long exercise.

Two chocolate Frappuccinos in a central Delhi coffee chain cost roughly Rs 1,000 (before taxes).

30 KMs away, Booth Level Officer or BLO Kusuma (name changed) in Dadri, Uttar Pradesh, will earn the same for what she describes as “soul-crushing” work under the month-long Special Intensive Revision being carried out in nine states and union territories.

She is one of more than 2,000 BLOs navigating the mammoth task of cleaning up voter rolls across the state.

Five BLOs have died by suicide in recent weeks, with families blaming the “extreme pressure” of SIR; at least eleven more deaths have been attributed to heart attacks and strokes that relatives link to the workload.

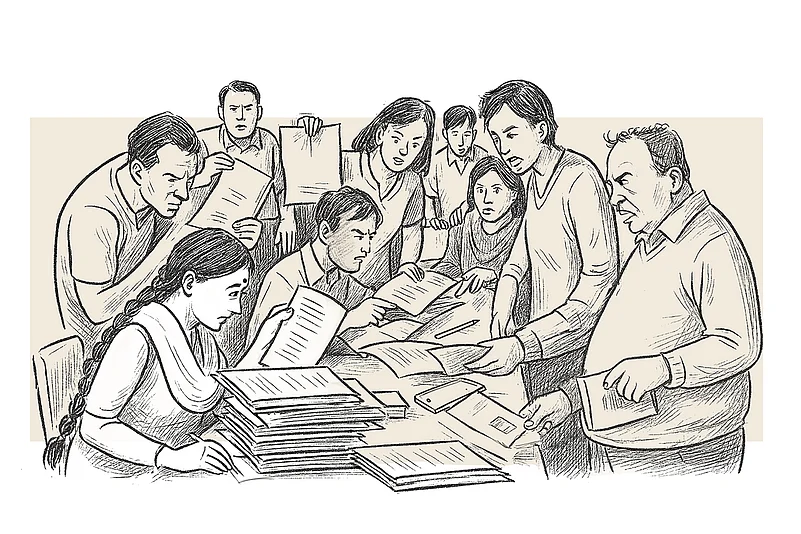

Outlook meets Kusuma in a plush residential society in Gautam Buddha Nagar. The clubhouse has offered the two BLOs a small room, without a working lightbulb. They huddle near a window to see the forms. Kusuma’s long braid falls past her waist; she wears sensible trainers with her pink-and-purple salwar kameez. A small bindi sits between furrowed brows, framed by dark circles.

“We’re here because society told the district office they felt unsafe with us entering the towers,” jokes her colleague, Jeet (name changed). “At least we don’t have to ring 1,000 doorbells now after distributing the forms.”

Both of them wake up at roughly 5 AM for their routine, but with the SIR going on, they go to sleep at 2-3 AM and still wake up before dawn.

Kusuma adds that men and women don’t have the same 24 hours in the day. “The men are suffering too; the pressure is such. But for us, we get up, clean and cook, get kids ready for school, do school work for kids, then do SIR all day long on the field, get home, wash clothes, cook dinner, bathe the children, serve my in-laws, then sit back with the phone again to digitise. My brain is broken now, I feel I have no soul left inside me,” she adds, how the constant berating and humiliations by authorities or even voters impact them daily. “Kuch bhi bol dete hain ye slow kaam pe” (they use any words for slow work).

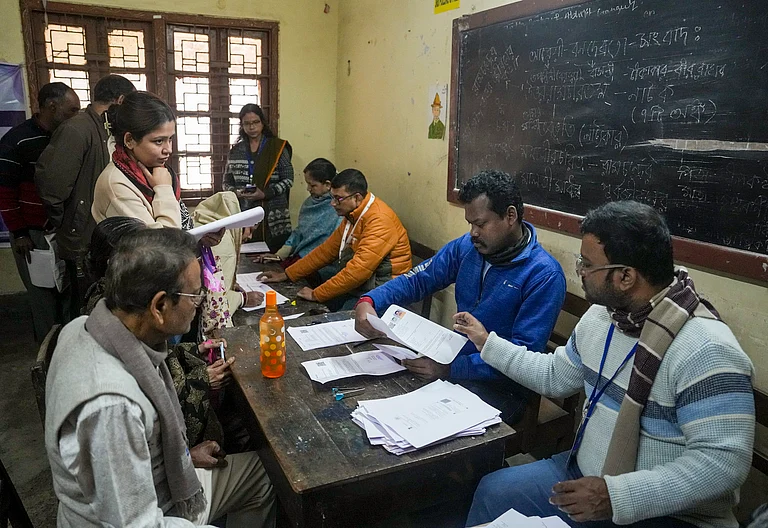

From 11 AM to 2:30 PM, residents arrive in an unending stream. The pair collects filled SIR forms from voters occupying roughly 1,800 flats here. They started distributing the forms on November 3, going door to door in each flat and spending roughly 20-30 minutes with each family to explain the process. Now, some families are here to return the filled forms, while others are here to collect forms for transfers or mutations.

Confusion is universal. People forget pens. Many lack documents; some have filled in incorrect details that are not relevant to the form's columns. One man demands an SIR form for his 15-year-old son, despite being told that children under 18 cannot vote; hence, he is not part of this exercise.

Another asks if an Aadhaar number will suffice in place of a voter ID. Even here—in a well-educated enclave—Kusuma and Jeet are besieged by questions. Their personal phone numbers have been shared with 800–1,200 voters each. They field calls at all hours, often while supervisors ring incessantly for hourly updates.

“I’ve explained everything during door-to-door visits,” Kusuma sighs. “They have internet. Fancy phones. Why can’t they look things up?”

Neither has eaten. Water costs Rs 20 and requires a five-minute walk. “Better saved for the tuk-tuk to go home,” she says. Just then, Jeet is trying to remain calm as a woman complains that her form has to be there; she voted in elections in UP before. Jeet explains the enumeration form must have an issue; maybe something else is amiss. After roughly 15 minutes of back-and-forth, the woman admits she was a voter in Kanpur but expected her name to be present since she ‘bought a home here last year’.

There are other issues, too, “Koi safety nahi hain public bhadak jati hai to use bhi jhelna, har din badtameezi kar te haan log,” (there is no safety, people get angry at us and misbehave.” BLOs are not allowed to take any casual or sick leave. A 2-month pregnant woman in Patna begged to be relieved of BLO duty, it is alleged by her school colleague. Her choices were simple: do the duty or face suspension.

Back in Dadri, just past noon, a girl of about eight arrives on behalf of her mother, who is worried that because the family’s new flat is in her husband’s name, her vote might be struck off. Kusuma tells the child she cannot help unless she has the mother's voter ID. Put on speakerphone, the mother mutters, unaware that Kusuma can hear her: “This aunty will be difficult, these women have too much attitude and power. Go to the male BLO.” Kusuma meets our gaze; the faintest flicker of her eyelid conveys a day’s worth of humiliation. In her regular job as a government teacher, she is treated with respect. Here, she absorbs the brunt of everyone’s irritations.

For Rs 1,000 a month (apart from her teacher’s salary, which is also low, in her words).

Travel, food, phone data, printing, pens—BLOs shoulder every cost. In rural areas, many must also fill out forms for voters. One such BLO, Sangeeta (name changed), breaks down when asked about phone data. “The digitisation app eats so much data. I can’t afford it. I’m exhausted.”

Initially fearful to speak, she hung up during our first call. In the second, she whispered, “Please don’t ask me anything. If my supervisor hears, there’ll be an FIR against me.”

Indeed, in Noida, more than sixty BLOs now face police cases for “dereliction of duty”, filed by the District Magistrate's office, under the authority of Medha Roopam, daughter of India’s Chief Election Commissioner Gyanesh Kumar. Officials insist FIRs will “speed up” the work. As of 24 November, only 22 per cent of forms had been digitised, piling pressure on both BLOs and administrators.

The office defends the FIRs. “If someone at your office is not performing well, don’t they get disciplinary action?” a highly placed official at DM office, GB Nagar, asks. His junior informs us that these FIRs will induce a little more urgency among the BLOs to complete the SIR before December 4.

As of November 24, only 22 per cent of the total received forms had been digitised according to DM office sources, adding immense pressure to the BLOs and the DM office. On being asked whether a little harsh-toned word from a boss is the same as a legal court case or a police FIR, there is no response.

“How can we meet the deadline?” asks Savita (name changed). Savita is in charge of a ward in a small village outside of Dadri. On 23 November, she collected sixty forms; her supervisor demanded 120.

“I digitised all sixty by midnight. My phone barely works unless it’s charging. I told him I’d done what I received. But he wanted 120. How do I create forms out of thin air?”

In Bihar, one BLO admits—unverified—that colleagues occasionally sign forms for families living out of state. “What else can we do?” asks the history teacher.

A BLO from the maths department is more direct: “Those suicides in Bengal, Kerala and Gujarat—this is on the Election Commission. Gross mismanagement. They are breaking their own rules and dumping everything on us.”

One such rule – BLOs must be assigned to their own locality. “They rarely follow it,” he says. “If someone from Patna City has to handle Kankarbagh, how will they even find people? Of course, the pressure kills them.”

On Tuesday, multiple resignation letters were filed in Gautam Buddha Nagar. Their fate remains unclear. One BLO near Jewar, caring for a mother with cancer, tried to resign. “They told me: finish all 900 voters first. Then you can do whatever you want, leave tomorrow if you can finish 900 in one day.”

He is a ‘Siksha Mitra’ or a contractual teacher who earns Rs 10,000 a month. His wife’s salary covers the cost of two young boys he has hired to help digitise forms. He handles the door-to-door work; they upload the data. “At least twelve of us have hired help; we don’t know much about using phones and technology. I even fail at trying to search for YouTube videos; this work is too complicated for technology dud like me,” he says.

This, says Jeet, is precisely the sort of pressure that has pushed some BLOs over the edge. One resignation reads: “I have been a teacher for twenty years, but the behaviour of authority figures during this duty is mentally distressing.” Another: “I have completed 215 of my 1,150 assigned voters with all my resources. I cannot go on. Forget BLO work—this has broken me so much I can no longer be a teacher.”

Most BLOs are teachers or anganwadi workers from rural areas, often without fast internet or smartphones capable of running the app. After trudging through door-to-door rounds, they spend evenings digitising hundreds of forms.

“Why do offline forms at all?” asks Savita. “If I must digitise everything at home anyway, what’s the point? It takes at least 10 minutes per file with my connection speed. I have hundreds. How do I invent more hours in the day?”

Before packing up the groundwork, she shares how the recent suicides have impacted her and other BLOs mentally. "We understand why they did it. We are working 16-17 hours a day, for no money, with the threat of FIR and suspension from the job. When I became a teacher, I had never imagined my life would be like this," she says. Just like her, other BLOs echo the same sentiment. "It was one thing if we got money at least; here it is just humiliation while emptying our pockets for games these politicians want to play," says the Maths teacher from Patna.

Before heading home to do her online BLO work, Savita calls the one-month deadline “atyachaar”—an atrocity. Then, quietly, she adds: “If I die under this pressure, who will raise my daughter?”