Nishaanchi 2, directed by Anurag Kashyap, released on Prime Video on November 14 along with its predecessor.

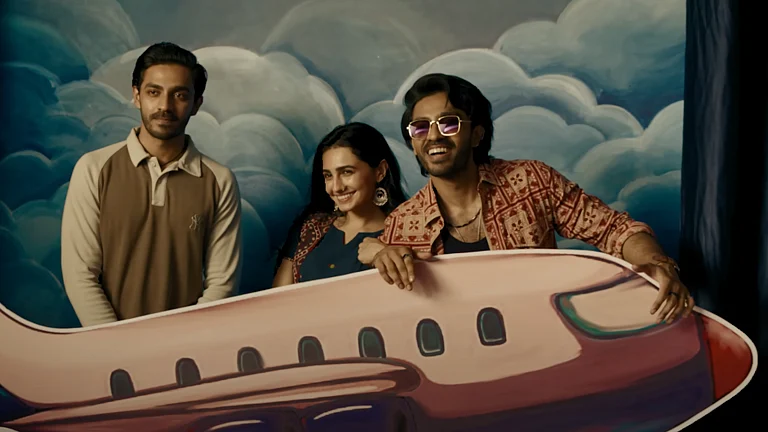

The film stars Aaishvary Thackeray, Vedika Pinto, Monica Panwar, Mohammed Zeeshan Ayyub, and Kumud Mishra.

The franchise features promising performances and melodrama, characteristic of Kashyap’s films.

Nishaanchi 2 (2025) opens in Lucknow with a restraint that immediately signals a shift from the first film’s brash Kanpur prologue—no “fillam dekho” theatrics, just a quieter recalibration of its world. The Nishaanchi franchise positions itself as a crime saga tracing the fraught destinies of identical twins Babloo and Dabloo (Aaishvary Thackeray), Rinku (Vedika Pinto), who plays the woman they both love, and the political machinery that consumes them. What begins as a compact drama of betrayal and divided loyalties gradually stretches into a broader reflection on power, masculinity and inherited violence—though not always with the confidence the material demands.

The first film charted the implosion of a family and the rot that seeps through its foundations. Rage, grief, and betrayal erupt in contained bursts, shaping two sons—Babloo and Dabloo as products of a violent lineage they do not fully understand. The sequel shifts its gaze to the aftermath: a family attempting to rebuild through the exhausting labour of simply staying afloat. Part two begins with Babloo’s return to a home that has reorganised itself in his absence. A line from the sequel summarises his condition: “You think you’ve returned from jail; you’ve locked yourself within.” Despite its implications on the interior conflicts, Babloo’s real captivity lies both within himself and the outside world that refuses to let him evolve.

The twin trope has always been a Bollywood staple, yet Kashyap uses it to track how personal trauma mirrors societal decay. Where the sequel briefly finds its footing is in its interrogation of the vigilante arc. The film treats his fate less like heroic martyrdom but as the by-product of a family history that repeats itself. Dabloo, gentler and perpetually overshadowed, promises their mother Manjari (Monika Panwar) that he will restore their family’s dignity.

The brothers, birthed under the same roof and raised under the same conditions, embody the franchise’s thesis: masculinity fractures into forms shaped less by personality than by circumstance. One becomes the adored rebel, the other the quiet shadow, but neither emerges as the true “hero.”

Monika Panwar, however, is the franchise’s conscience. Her Manjari is written as a woman repeatedly denied authorship over her life, yet Panwar plays her with a composed fury that eventually detonates. The mother–daughter-in-law dynamic between Panwar and Pinto is a quiet surprise: a knot of resentment, empathy, judgement and reluctant solidarity. It cuts through the film’s masculinity-heavy landscape with needed clarity.

Thackeray’s performance is its most consistent strength. He avoids caricature, shifting between Babloo’s hard edges and Dabloo’s vulnerability with small, precise decisions rather than theatrical contrasts. It is an unshowy but deeply controlled portrayal, especially in Nishaanchi 2, where the emotional weight falls squarely on him. Pinto, too, benefits from a script that finally grants her agency, giving Rinku a journey that tracks the shift from attraction to safety. Her movement from Babloo’s magnetism to Dabloo’s reliability reflects what survival looks like when dignity becomes non-negotiable. The real pivot, however, is her own self-preservation; the films refuse to turn the love triangle into a referendum on which man loved her more. Her confrontations with Manjari form some of the franchise’s most honest moments—two women negotiating loyalty, grief and self-preservation without theatrics.

Both films are anchored in a world that imagines itself at the edge of collapse: a quasi-vigilante state with the façade of democracy, where the criminal–politician nexus shapes the UP hinterland. It is a landscape where justice appears mythic rather than procedural and where the line between survival and submission is drawn by men like Ambika Prasad (Kumud Mishra)—a mentor, godfather and executioner rolled into one.

The franchise wants to expand this universe, yet the expansion reveals the limits of its internal logic. For all its thematic ambition, the franchise struggles with pace. Both films contain sequences that really stand out, especially when focused on the central trio, but the connective tissue is often slack. The midsection of Nishaanchi 2 drifts off noticeably. New characters enter with little organic build-up, and the plot contorts itself to reach an ending the audience can predict. Entire scenes and characters exist only to advance the plot, weakening the emotional throughline. Babloo’s struggle to live with dignity prompts a tentative yet unnecessary romance with influencer Anjana (Erika Jason).

The music in Part 2 underlines every narrative beat with near-ritualistic predictability and isn’t as memorable as it was in its predecessor. The editing in Nishaanchi 2 especially suffers from an odd duality: the climax feels overdue, yet takes an eternity to arrive. The long lead-up and the eventual payoff doesn’t fully justify the wait, though it truly deserves a moment of admiration. Even if one were to talk about the climax it would be impossible to do so without spoilers although, Panwar’s command over the film’s emotional terrain is mesmerising. The impact lies in how it confronts consequence rather than distributing catharsis.

Across their combined five-hour runtime, the films offer flashes of sharp writing, memorable dialogue and compelling set pieces, yet the whole never coheres as convincingly as its parts. It raises the inevitable question: would Nishaanchi have been more effective as a single, tightly-edited film? The second film improves certain ideas but also inherits the narrative fatigue of the first, leaving the impression of a franchise that recognises its potential but cannot consistently execute it.

Still, the films are not without cultural value. Beneath the structural missteps lies a sensibility that once shaped mainstream Hindi cinema: an instinctive blend of heightened emotion and social critique. Ironically, this tradition now feels estranged from the theatrical landscape that once embraced it. The quiet release of Nishaanchi 2 in OTT feels emblematic of the fading space for mid-budget, morally textured masala dramas. Nishaanchi remains a franchise brimming with ideas—some urgent, some scattered—but rarely in command of its storytelling. What it lacks in cohesion, it compensates for with sincerity and strong performances. And if the filmmakers ever return for a definitive cut (wishful thinking, but one can hope), there is a sharper, leaner, far more resonant film waiting inside the one we currently have.