Indian cinema’s early portrayals of mental illness — Films like Khilona (1970) and Khamoshi (1970) relied on melodramatic, implausible plots and exaggerated mannerisms, reinforcing stereotypes about mental health.

International benchmarks and mixed realism — While performances in films such as One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Rain Man, and A Beautiful Mind were celebrated, their depictions of mental health still carried oversimplifications or problematic narrative framing.

Notable nuanced portrayals in Indian cinema — Works like Sadma/Moondram Pirai, certain Kamal Haasan performances, and Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s Elippathayam and Anantaram offered more sensitive, layered explorations of psychological states and human vulnerability.

‘ooOOO…khilona…jaan kar tum to mera dil tod jaate ho…ooOOO…khilona’. This plaintive cry by Mohammad Rafi, picturised on a maudlin Sanjeev Kumar in tattered white kurta and fake beard, clutching the bars of a locked room, pleading with Mumtaz who is walking away with a suitcase in hand not to leave him, clouded a whole generation of Indian cinegoers about the idea of mental illness portrayed in popular cinema. Some sadistic babu in Mandi House made Doordarshan play this song week after week on its film music show Chitrahaar.

The film was Khilona (1970), a superhit then is unbearable to watch now. It has this impossible premise of a thakur hiring a courtesan (Mumtaz) to playact as wife to his son Vijay Babu (Sanjeev Kumar), who is simply said to have become ‘pagal’, with a view of ‘curing’ him. Mumtaz enters a hostile household, is raped by her ‘ward’ one stormy day, is accused of various things by the various members of the family, and after many twists and turns it takes Vijay Babu’s younger brother Mohan (Jitendra) in an emotional outburst to clear the air in the climax, and to unite the lead pair.

The film is problematic on many counts when viewed now. But its biggest crime is this prototype of a character with mental illness—dishevelled clothes, unkempt hair and vigorous rolling of the eyes. The more serious film on mental health from that time is Khamoshi (1970), which too was a DD favourite. When seen now, its melodrama quotient may be much lower than Khilona, but its premise is as implausible. Here, the chief of a psychiatry ward, Colonel Sahab (Nasir Hussain) is determined to cure patients with ‘acute mania’ with his own methods which is primarily to make one of the nurses of the ward, Radha (Waheed Rehman), fake a romantic relationship with the patient and withdraw when the patient is cured. Many ‘psychiatry’ terms like schizophrenia, paranoia, hysteria, panic reaction, narcissism, Oedipus and Electra complex are thrown about.

At the beginning of the film, Radha has already successfully cured one patient Dev (Dharmendra, who is wasted as he is never fully shown in the film) by this method. Of course, in the process of playacting, Radha has fallen in love with Dev and is heartbroken by his departure. When another patient with a similar mental health issue, Arun (Rajesh Khanna), comes to the ward and Colonel Sahab entrusts him to Radha, she refuses. She can’t go through another round of this playing lover but the chief admonishes her. She starts caring for Arun, who is a poet and writer, and again gets emotionally involved. When Arun is cured, and he can’t remember anything that Radha did for him, she loses her mental balance. The film ends with Radha being admitted to the psychiatry ward.

Khamoshi gained respectability for its black and white cinematography, excellent music score by Hemant Kumar (Tum pukar lo…still hummed tunelessly in cocktail parties after the fourth rum by balding men in their 60s and 70s) and lyrics by Gulzar (Hamne dekhi hain in ankhon ki mehkti khusboo and woh shaam kuch ajeeb thi…) and a fine turn by Waheeda Rehman. But Rajesh Khanna hams his way through his mentally disturbed character (He has been jilted by his rich girlfriend), the film is loosely written and there’s even an item number.

It will be five years after Khilona and Khamoshi when Randle McMurphy will shock the world and fly above all the movies ever made on mental illness or set in a mental asylum. Before One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest stormed global audiences, Jack Nicholson had already spent a decade in Hollywood, acting in low-budget films and writing a few. He had already made people notice him in Dennis Hopper’s road movie, Easy Rider, and Roman Polanski’s Chinatown a few years before Cuckoo’s Nest. But Nicholson as McMurphy owns this drama set in a mental asylum, with his full range of histrionics, and a glimpse of what’s to come over the years in films like an unhinged writer in The Shining, as the evil maverick Joker in Tim Burton’s Batman, the egoistical armyman in A Few Good Men, as a person with OCD in As Good As It Gets, an irascible old man in About Schmidt, his comic timing in Anger Management and so on.

On viewing Cuckoo’s Nest now, Nicholson (who won his first best actor Oscar for this role), comes across as charismatic as when seen for the first time—his rebellious, finger-to-the-authority attitude, his camaraderie and compassion with the other inmates, his raging and cold anger against authoritarian Nurse Ratched—are all spot on. But film itself has aged, its portrayal of people with mental health issues with their exaggerated mannerisms and ticks is no better than in Khamoshi. Besides, McMurphy is in the institution charged with raping a 15-year-old minor girl, a fact dismissed without any further investigation.

Over a decade later came Rain Man, Dustin Hoffman’s brilliant portrayal of a person with autism spectrum disorder. Charlie (Tom Cruise) is a hustler and creditors are after him. His father dies and leaves his entire estate to his elder son Raymond (Hoffman) who is in a mental institution, and about whose existence Charlie had no idea. This unlikely pair embark on a road trip as Raymond (that’s ‘Rain Man’, as Charlie used to call his big brother when he was a toddler) can’t take a flight.

The rest of the movie is about this bromance, with Hoffman giving an Oscar-winning performance. More than decade after Rain Man came another global blockbuster film with schizophrenia as the theme—Russell Crowe starrer A Beautiful Mind. This intriguing film based on the life of real-life mathematics genius Prof John Nash, takes the viewer along with Nash into his schizophrenic mind. The US government wants to use Nash’s mathematical genius to decipher secret coding by the Russians and help him spoil their plans.

Nash starts working for the enigmatic William Parcher (Ed Harris) and gets deep into US-Russia espionage. At one point there is a shootout between the two groups of spies after which Nash wants to quit working on this project but Parcher won’t let him go. Only halfway down the film the viewer is let on that this whole espionage thing is only in Nash’s schizophrenia. There is no real person called William Parcher, these are events and people only in the professor’s mind.

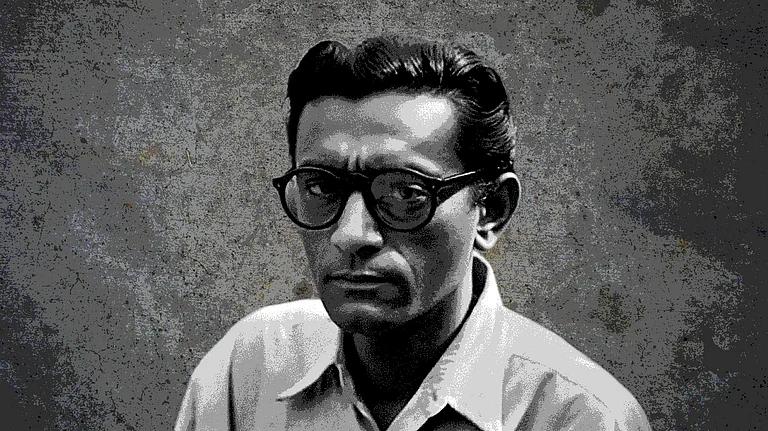

In Indian cinema, the shape-changing Kamal Hasan’s has perhaps portrayed the maximum number of characters with mental illness and physical disabilities. From the bucktoothed Kalyanaraman (1979) to the dwarf in Appu Raja (1989), from a person with autism in Swathi Muthyam (1986) to a psychiatric patient in Gunaa (1991).

The last one, considered a cult classic, on re-viewing reveals a very violent streak and a convoluted plotline. Gunaa (Kamal Hasan) is in an mental institution. He is obsessed with an imaginary beauty called Abhirami whom he his fated to wed. He comes across a rich heiress at a temple event and believes she is Abhirami. Gunaa kidnaps her to a cave, and after initial attempts at escaping from him, she develops some kind of a Stockholm syndrome. Then the villains step in, there is a lot of bloodshed, Abhirami is shot, and finally Gunaa jumps off a cliff clutching his lover’s body. It’s very much a masala film but what lifts it is Kamal Hasan’s portrayals of the central character.

It is another Kamal Hasan film, where not he but his co-star Sridevi’s character who has a mental illness, which stands up for its sophistication and sensitivity even today. The film is Balu Mahendran’s Moondram Pirai, re-made in Hindi as Sadma with the same lead actors. Its haunting music score, moody cinematography in the misty Nilgiri hills and sterling performances both by Kamal Hasan and Sridevi makes it a riveting watch. Vijaya (Sridevi) is involved in a car accident where she suffers a head injury. Doctors say she has got retrograde amnesia and has regressed to when she was six years old. With some quick plot points, it’s set up that Cheenu (Kamal Hasan), a school teacher in a hill town, has to take care of her. The soul of the film is this relationship between the two, with some great Balu Mahendran touches of wit and winsome scenes.

In Malayalam cinema, auteur Adoor Gopalakrishnan has dealt with mental illness in many of his films. His Elippathayam (Rat Trap, 1982) is about a decaying feudal lord Unni (Karamana Janardhan Nair), a kind of an Oblomov, disinterested in anything in life. For selfish reasons he doesn’t let his sisters marry, for there will be no one to take care of him. It’s a grim setting, most of the film shot in grey light, the brooding Unni who not able to fight the demons in his head finally is trapped in his crumbling house like a rat in a trap.

A few years later, Adoor’s beguiling Anantaram has an unreliable narrator in its protagonist Ajayan (Ashokan), who in the voice-over says was a brilliant student, a good swimmer and sportsman but he couldn’t blossom due to the rigid education system. Later it’s revealed that he flunked in his class and is terrified of water. Then we meet a college-going Ajayan, who is helplessly drawn to his step brother Dr Balu’s (Mammootty) wife Suma (Shobana). In his mind, she is the same girl Nalini he met in college who had fallen in love with him. Now, the viewer doesn’t know what’s real and what’s in Ajayan’s imagination. There is a line towards the end when Dr Balu tells a distraught Ajayan to take his medicines and go to bed. What are these medicines for? Adoor wont’t explain, leaving the viewer with a sweet dilemma.