The Government of India formulated its first Mental Health policy in 2014.

Mental health is less than 0.16 per cent of India’s health budget.

India has 0.3 psychiatrists, 0.12 nurses and 0.07 psychologists per 100,000 people, among the lowest on the World Health Organisation’s global listings.

India has a quietly brewing mental health crisis. While the government has policies in place, a huge number of Indian citizens do not have access to mental health care. Meanwhile stigma creates a divide between those who need treatment and those who can seek it out.

A Policy for a Burgeoning Crisis

The Government of India formulated its first Mental Health policy in 2014. The aim was to integrate mental healthcare services into general healthcare to close service gaps and foster and educate a community for those in need.

In 2017, The Mental Healthcare Act (MHCA) decriminalised attempted suicide and made a person’s the right to mental healthcare a law. The MHCA framework was an ambitious one but the reality on ground for India’s mentally-ill persons is starkly different—mental health is less than 0.16 per cent of India’s health budget.

Ground Realities: Coverage and capacity shortfalls

In 1947, after the formation of India, the country had a custodial model of care of the mentally ill. The focus was on large mental health treatment institutes. The National Mental Health Programme (NMHP) and its District Mental Health Programme (DMHP) were instituted to shift the focus from custody to community. It was only in June 2018 that DMHP became operational in 90 per cent of India— 655 of 724 districts. However, quality and continuity of services is uneven.

To date, India has only 0.3 psychiatrists, 0.12 nurses and 0.07 psychologists per 100 000 people, and is among the lowest on the World Health Organisation’s global listings.

Treatment gaps

The National Mental Health Survey (NMHS) 2015–16 showed that 10 per cent of Indians have a mental disorder, but within this, only 15 per cent receive any treatment. Treatment gaps range from 90 per cent for common disorders to nearly 70 per cent for severe disorders. Rural areas and marginalised groups are worse off than urban populations, which reflects the inequity in mental health infrastructure.

Patchy Policy Implementation

Despite legislative mandates, state-level execution is patchy. There are only a handful of Mental health review boards which are statutorily prescribed under the MHCA 2017.

Moreover, the Act emphasises individual autonomy which is at odds with India’s family-centred caregiving model.

Stigma: The Invisible Barrier

One in five young people in India have discriminatory views of those with mental health disorders. Often, such people, who need help, are seen as lazy, or dangerous, or hopeless. Almost one third of the survey subjects didn’t believe in psychological disorders at all.

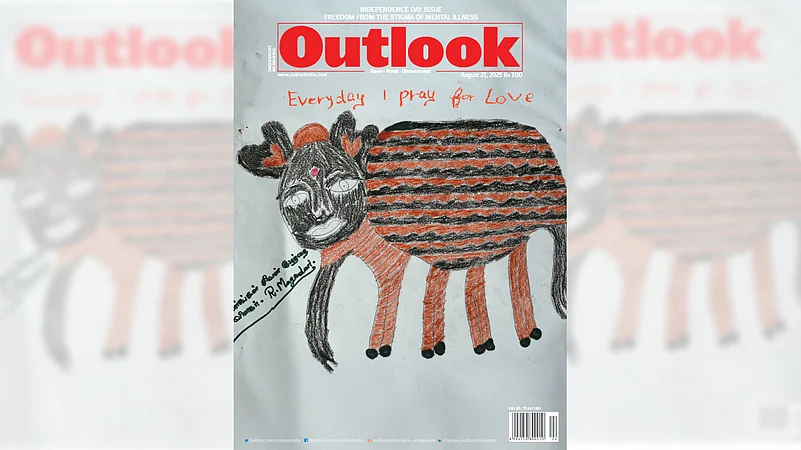

In its August 21 issue, Outlook collaborated with The Banyan India to take a hard look at the community and care provided to those with mental health disorders in India. From the inmates in mental health facilities across India—Ranchi to Lucknow—to the mental health impact of conflict journalism, to the chronic stress caused by the caste system, our reporters and columnists shed light on and questioned the stigma weighing down the vulnerable communities where mental health disorders are prevalent.

Mohamed Asghar Khan writes about the inmates of a century-old mental health facility near Ranchi who are desperate to leave but have been deemed too “ill” to live with others in society.

In Uttar Pradesh, Swati Subedar looks at the efforts being made In Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state, under the District Mental Health Programme to help people with mental illnesses. She found that a large section of disadvantaged society is still slipping through the cracks.

Toufiq Rashid writes a personal account of the toll conflict journalism takes on reporters. “Covering conflict is dangerous, but it becomes even more hazardous when the conflict zone happens to be your motherland,” she writes.

Meanwhile Vineeta Mokkil looks how women, especially, are often silenced, stretched thin, or made to feel small when they try to access care services. Mental health needs to be reframed as a human right, she writes.

Avantika Mehta examines the psychological toll that the caste system takes on scheduled caste and scheduled tribe communities. The mental health care infrastructure for SC/ST community is nearly non-existent she found, while adding that caste itself is a major cause of psychological disorders and chronic stress.

Pragya Singh explored the connection between mental health policies and India’s socio-economic structure. She found that community care was the missing link between those with mental health disorders and general society.

Through these voices, Outlook in collaboration with The Banyan hope to spark conversations in drawing rooms across India that reflect on mental health experiences in all their diversity. We want readers to understand that supporting mental health means recognising it as inseparable from human dignity, social justice, and authentic freedom.

To this end, the stories on these pages are neither immersive tragedy or exceptional inspiration, they represent truth. And truth, however ambiguous or uncomfortable, is the foundation of any meaningful social change.