Nidhi Saxena hones a language of whispering delicacy in Secret of a Mountain Serpent

Myth and reality conjoin as the film gestures to collective emancipatory affirmation

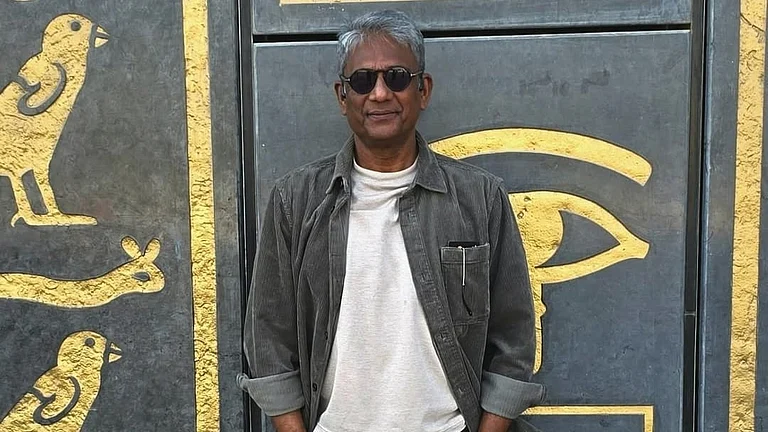

Trimala Adhikari and Adil Hussain are fully in sync with Saxena's sublime, transporting leaps

“War swallowed all our men,” someone remarks early in Nidhi Saxena’s Secret of a Mountain Serpent. Foraging through ashes of war, Saxena crafts a tableaux of women’s lives—what remains of their tenuous hopes and dreams when men have all but disappeared. But the binds still clinch as tight. Out of scattered residues wells up a film where every gesture is measured, holding something latent, charged and intensely private. But even as we’re taken through an intimate isolation, the fact that it’s a shared experience for many women—who flit through the film’s edges—hovers. Reserved personal whispers fly out high and wide, pining for faraway lovers and partners. But does distance deepen the love, or spur forgetfulness, an emotional tearing apart? To watch Secret of a Mountain Serpent is to inhabit a conflicted prayer, torn between longing and denial. Saxena absorbs us within a fabric of repressed yearning, where mores and identity run in silent, throbbing tension. Expanding with gorgeous aural glisten, this film keeps every promise Saxena made in her criminally under-seen debut Sad Letters of an Imaginary Woman (2024).

Planting us in Almora, losses wrought by the Kargil War hang in the air. In this plaintive fable, the unsaid, the withheld thrum with insistent force, as manifest in Trimala Adhikari’s graceful, intuitive performance. The town is bereft of men, fathers and husbands away in the war. Irrespective of uncertainties about ever being reunited with their partners, the women are firmly locked within unspoken codes of morality. Rekha Bhardwaj croons dolefully, “He has forgotten all promises; why do I still keep remembering him?” Desire is situated at a crossroads between norms and untethered expression. There are too many social and cultural mediations weighing them down, limiting choice and mobility.

An elegant and poised image-maker, Saxena looks into the unfilmable pores of human feeling and sketches a subdued, rich emotional panorama. As Barkha, one of the many women with absent husbands, the ever-reliable Adhikari never strains to impress or elaborately move us. Saxena trusts her abundantly to convey a depth in the quiet—it’s a marvel to watch the actress deftly move through the most delicate delineations. Despair, tentativeness, fear and delight lightly flicker through her mien. Barkha has sunk into a kind of unruffled resignation, going through her teaching work listlessly. Something shifts when she meets Manik Guho (Adil Hussain), who drops out of nowhere.

Hussain’s airy, translucent presence deploys every movement towards the otherworldly. There’s a quicksilver, shapeshifting energy he conjures, blending in and out of the elements. He’s like vapor, slipping out of touch even while summoning a moment of great intimacy. Time comes to a standstill in the scenes Adhikari and Hussain share. These initially appear as islands of reprieve in the film until they radiate outwards. Patient, minute and transporting, Saman Alvitigala’s edit whisks us through extraordinary transitions in the middle of mundanity.

“To belong everywhere is to belong nowhere”, Barkha muses, after Manik professes a fluid identity. He doesn’t wish to consign himself to a particular location; instead, he remolds himself with every change of setting. He arrests her completely, his poetry offering a freedom of reimagination. Guho elicits incantatory swings in the film’s world.

Like in her previous film, Saxena embeds spaces with vivid, palpable texture. Here, of course, the ambit is much wider, ranging beyond house and habitation to eke out immersion in nature and landscapes. The unbound ecology is drawn in breathing, living tandem with lonely, straying souls. “I’ll whisper to the trees,” Barkha murmurs across space to her remote husband. Elsewhere, in the army quarters, a flock of birds thrash around before him, her words ringing, “Did you miss me?”

In scene after scene, DP Vikas Urs (who’s also behind the year’s two other gems, Sabar Bonda and Vaghachipani) weaves breathtaking compositions. There are lovely images of women in repose and stillness, tucked away from male vicinity as well as being part of sisterhoods. There are strains of disagreement that eventually bound towards common assertion. Shots of a yard of sari billowing against the blue sky and a tree’s blossoms linger as soothingly as a static of a woman eating an apple, a stream gurgling just below, or Barkha resting under a tree. An outline of distant peaks feels as tantalizing as a hidden urge to renew oneself. Nature’s calming canopy becomes their haven, despite it too having certain regimentations. There are routes and areas forbidden for women. An ancient snake myth linked to a river sets off the drama and keeps coloring its contours. Some subscribe to the myth, insisting on recent sightings, while others are cynical. The myth begins to feel more real, leaking into regular conversations. Entwining a forest, serenity, punctuated communities of schoolchildren, migratory birds and huddled women, Saxena sublimates us in emotional and spiritual spaces unclipped by the tangible. We float through, as a collective ache for catharsis trails all women.

Draped over the film is a settled disaffection among the town’s women, a sadness that has whittled out every other emotion. Blue, a color Barkha loves—which also drenched Sad Letters of an Imaginary Woman—is thinly cast over this film as a mist. Barkha asks a colleague if she’s not happy that her husband and the town’s men are returning. The lack of a response is telling. In another instance, it’s Barkha who’s entreated to sort it out with her husband, Sudhir (Pushpendra Singh), who’s back. She wears the new shoes he’s brought her, but he’s been hollowed out by the war.

These sedimented expectations women have been long-saddled with and internalized emerge as their shackle. The spark to transgress—take full, glad ownership of their half-eroded wishes—may take any form, arrive via any track. Saxena gently appeals to our faith in cinema’s capability for metaphysical shifts. Man, animal, inanimate objects—boundaries soften into an innate belief in diversely embodied transformations and reckonings. Screen intercessions too thaw in a cheeky self-reflexive interruption—Adhikari breaking the fourth wall and asking Saxena about the coming turn of circumstances.

Secret of a Mountain Serpent builds a beautiful, humming tension in tranquility, even as magnificent temporal and spatial shifts reveal new angles. The past darts by as small visions, breaking the controlled emotional flow. Disconsolation among the women can lift when they themselves re-possess and haul out agency from the inhibited. Moving in exulting, liberatory directions, Secret of a Mountain Serpent wields a tremendous, hypnotic pull.