Haq portrays the personal struggle behind the Shah Bano case but avoids the political storm it triggered, which reshaped India’s legal and communal landscape.

The 1985 Shah Bano verdict began as a woman’s fight for maintenance but escalated into a nationwide clash over religious law, secularism, and political appeasement.

While the film captures Shah Bano’s emotional and legal battle with sincerity, it overlooks the larger political fallout that influenced decades of Indian politics.

What’s the most striking memory of the Shah Bano case of 1985 in public consciousness? Yes, it was the struggle of a frail, aging divorced Muslim lady’s fight to get maintenance for her children from her relatively well-off husband. Yes, it was about the highest court of the land deciding in her favour, a landmark decision when it came to the validity of the Muslim Personal Law in a secular framework. The film Haq based on the Shah Bano case is detailed and well-intended till this point.

But the case is even more important in the nation’s politics for the dramatic events that took place after the Shah Bano verdict was pronounced. The conservative Muslims, especially the men leading the All India Muslim Personal Law Board (AIMPLB), came out protesting the verdict, saying that it undermined the Sharia laws and the identity of the Indian Muslims. Under pressure, the then ruling Congress government of Rajiv Gandhi, which had a monstrous majority in the Parliament, winning 415 seats in the 1984 polls a year before, post Indira Gandhi’s assassination, passed The Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act, 1986, which effectively negated the Supreme Court verdict. Under this act, a Muslim woman would get maintenance only for 90 days, the iddat period enshrined in the Sharia laws.

Now, this led to a bigger uproar from the Opposition parties, particularly the Hindu groups, which called the Act nothing but appeasement of the minorities. Unnerved by this opposition, many analysts think the Rajiv Gandhi government committed another big blunder—it opened the locks of the Babri Masjid that had been closed since 1949 when an idol of Lord Ram was placed inside the mosque. It would, of course, be too simplistic to draw this cause-and-effect analysis of the politically charged mid-1980s, but the rush of devotees at the Babri Masjid the moment the locks were opened do point towards the events that would lead up to its demolition eight years later.

That, in turn, unleashed the Hindutva forces, made the Bharatiya Janata Party the formidable force it is today, and changed the idea of India forever. The nation is still in the throes of these cataclysmic changes and we don’t know how the present will be viewed, say 50 or 100 years hence. Again, it may be too much to credit one Shah Bano case to the political upheaval of the last 40 years, but just as Archduke Franz Ferdinand’s assassination is said to have sparked World War I, the case was a turning point in Indian politics.

The film Haq doesn’t venture anywhere near the events that followed the judgement, except as a short note before the credits roll. It keeps itself to the chronological telling of the life of the lady in distress, called Shazia Bano in the film. But the part of the case it deals with, it does so with utmost honesty and attention to detail—if anything, it gets caught too much in the trees and misses the wood.

Shazia Bano (Yami Gautam Dhar) and Mohammad Abbas Khan (Emraan Hashmi) gleefully say qubool hai when the qazi asks them for their assent to the nikah. They are a happily married young couple giving each other succour. In an early scene, when a boorish neighbour yells at Shazia for planting flowering plants in his part of the compound, Abbas Khan buys off that bit of the plot for Shazia. Things go delectably well, enveloped in the aroma of biryani and burfi, till Abbas says he has to go Pakistan on urgent business, along with his mother. There are no phone calls or letters for three months, and finally when he returns home, it is with a second wife Saira (Vartika Singh).

Shazia’s world turns upside down, as from then on her relationship with Abbas sours. She also learns Abbas and Saira were lovers when young; she gets forcibly married to another man who has died prematurely. Abbas, who was attracted to Shazia for her bold views and innate sense of justice, finds her quarrelsome and intrusive now. He gets more and more immersed in his work, and in Saira’s charms, and Shazia, now with three children, is left to fend for herself. She confronts Abbas but their differences are irreconcilable, the marriage ending in talaaq, talaaq, talaaq.

Shazia goes back to her parents’ house and her travails mount. After a few months, Abbas stops sending her money for running the house and bringing up the children. She pleads with him, but he defends himself saying he has paid her according to the Sharia laws. Shazia, helped by her supportive father, decides to take Abbas to court. The lower court decides in Shazia’s favour, but gives her only a paltry sum for maintenance. She knocks at the High Court. By now it is no longer a case of maintenance by a divorced couple as the case has hit news headlines. Abbas plots to deliberately lose the case in the High Court as he wants to take it right up to the Supreme Court, where he is certain he will win because of the precedent. He also makes it an issue of minority freedom, Muslim personal law versus the secular legal framework and Muslim identity in a Hindu-majority India.

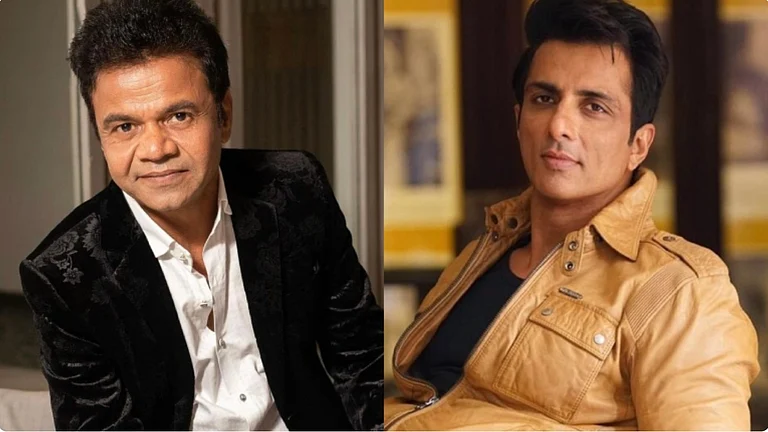

This is about how political the film gets. To filmmaker Suparn Varma’s credit, he keeps the film tonally understated. There are no shrill, trenchant moments taking on the ills of Islam. Both Hashmi and Dhar get their monologues, and even these though emotionally charged are not over-the-top sermons. Both the actors live their characters—Hashmi as the unlikeable husband is spot on and Dhar is both vulnerable and tough, as a simple girl who normally would settle any dispute amicably, but is forced to fight the system as injustice upon injustice is poured on her.

It would perhaps have been more interesting if the film had started with the case in the Supreme Court, how Abbas wanted to make it a bigger issue than a personal fight, the clash between the hardened Muslim clerics and the rising Hindutva groups, and how the case has been a trigger to the politics we are witnessing today in India. That may be another film, for another day.

This article appeared as 'Shah Bano's Ghost' in Outlook’s December 1, 2025 issue as 'The Burden of Bihar' which explores how the latest election results tell their own story of continuity and aspiration, and the new government inherits a mandate weighted with expectations. The issue reveals how politics, people, and power intersect in ways that shape who we are—and where we go next.