The massive mandate in Bihar to the incumbent National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government is being hailed as an outcome of a ‘dushazaari chunav’—a reference to the distribution of Rs 10,000/- each to almost 1.5 crore Jeevika Didis of Bihar. Many women beneficiaries of this scheme are reported to have used this money to buy goats, one of the most basic forms of animal husbandry businesses available to women in the state.

In this article, I will argue for the need to view this mandate beyond the lens of immediate monetary transaction and through a long-term security perspective.

Let me therefore begin this article with a story about goats that I had heard in Bihar back in 2015. A group of men from a Tatama tola in the Taal area of Mokama explained the meaning of susashan in the following words: “Nitish ji jo kiye wo asambhav tha. Law and order ka raj matlab baagh (tiger) aur bakri (goat) ekko saath talab se paani pi sakta hai” (Nitish ji has done the impossible. The rule of law and order established by him means now a tiger and a goat can drink water from the same pond at the same time). It was interesting that his example was set in a jungle to clearly establish the difference between the idea of Jungle Raj and Nitish Kumar’s susashan raj.

In 2025 too, the election campaign reverberated with familiar sounds evoking the fear of Jungle Raj, along with a rehearsed cacophony of concerns over unemployment and migration, with most parties offering rather stopgap and ad-hoc policies of employment and fiscally imprudent policies of largesse and welfare distribution on a competitive mode.

As the incumbent, reigning over this economically deprived yet highly politically conscious polity for almost two decades, Nitish Kumar has built a credibility of weaving a large safety net of social welfare schemes, which have spun a complex, and sometimes complacent, web of dependence between the state and the electorate. From his bicycle schemes, old age pension, widow pension, skill development loans (up to Rs 2 lakh) and scholarships for the girl child, to money for school uniforms and distribution of cash to Jeevika Didis, the list of welfare service deliveries is a long one and thanks to an efficient distribution mechanism on the ground, there was hardly a single family that had not been touched by at least one of these schemes.

In addition to the economic sustenance facilitated by various schemes, the reservations in Panchayati Raj Institutions (PRIs), especially for the Economically Backward Classes (20 per cent) and women (50 per cent), have boosted political representation and agency for people hitherto unknown to such access to power.

The devolution of funds to the PRIs through an increased state capacity and an expanded budget for infrastructure development has boosted economic activities at the local level. Even if most economic activities are still highly centred around the state, there is an increased propensity to attach oneself to these various arms of the state in order to partake in some of these economic gains, especially among the youth who chose not to migrate outside for work.

In the panchayat in Samastipur district where I have been studying elections and local politics since 2015, a mobile phone shopkeeper, a wedding photographer, a graphic designer, a B. Tech graduate who is running a successful milk business and a B.Com graduate who is a local contractor undertaking petty infrastructure contracts all represent signs of an uptick in local economic activities that were non-existent 10 years ago.

While a lot of focus is put on migrating youth, it is also important to look at the activities and stories of those who chose to stay in Bihar and are try to latch on to the ever-increasing umbrella of the state.

Despite all this uptick in state-dependent economic activities, rampant poverty and precarity persist in the state, with around 35 per cent of the total families earning less than Rs 6,000 per household per month (average rural household monthly income in India is double that amount).

However, Nitish Kumar’s success lies in his ability to ensconce the poor and the marginalised with a safety net of a kind that has never been experienced in the state before. Beyond monetary transactions, this safety net is also reflected in the dignity that comes with political representation or with an increased mobility for women in well-lit streets of the villages, with her safety ensured in the prevailing rule of law. This change, though significant, is more status quoist, as it has been built assiduously over a long time.

The changes through a backward caste assertion in the politics of Bihar, tracing back to the times of Karpoori Thakur, were also built upon a long struggle dating back to the times of the Triveni Sangh in the 1930s. However, in the post-Mandal era, Lalu Yadav was able to fast-track that social churning into a political upheaval of sorts, which flipped the established structures of power in the state, hitherto dominated by the upper caste, replacing the baagh with the bakri.

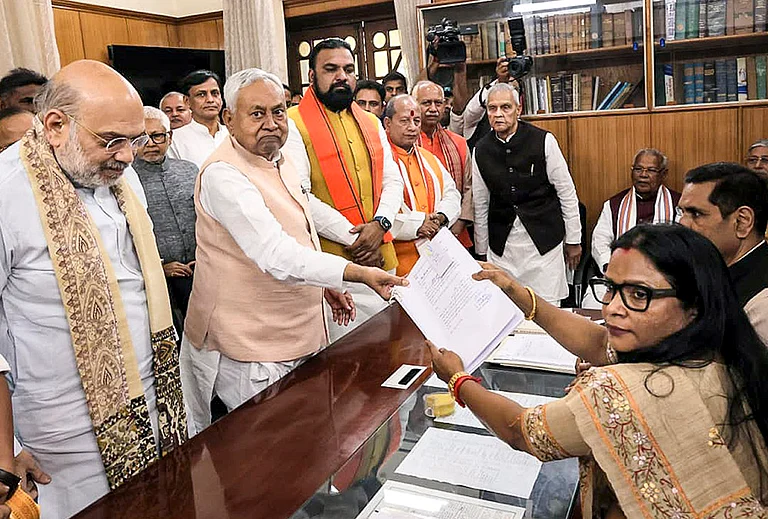

The rupture caused by such an upheaval also led to an outpouring of violence and the subversion of the rule of law, which ultimately translated and even amplified into the Jungle Raj narrative, something that refuses to fade even after two decades. Nitish Kumar has managed to bring about a change conducive enough for both the baagh and the bakri to drink water from the same pond. These socio-political and political-economic changes, which are also status quoist in nature, have, in turn, paved the way for the nine-time chief minister to stake a claim to be the GOAT (Greatest of All Time) of Bihar politics.

(Views expressed are personal)

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Sarthak Bagchi is a political analyst and researcher. His research interests are in Indian politics, identity politics, political mobilisation and global populism