The 27th Amendment to Pakistan's Constitution abolishes the Supreme Court’s role in Constitutional cases by establishing a Federal Constitutional Court.

The amendment introduces changes to Article 243 of the Pakistan Constitution and grants lifelong immunity to five-star rank Army Chiefs, allowing them to 'retain rank.

Several Judges from the Supreme Court of Pakistan have resigned, calling the 27th amendment a direct attack on Pakistan's judiciary and federal structure.

Is the Supreme Court of Pakistan the highest judicial body? Can military officers be placed above the law and legal consequences? The answer to both questions for most of the democratic world is yes, but a recent amendment to Pakistan’s Constitution has rendered the country’s SC toothless.

As the 27th Amendment to Pakistan’s constitution, with all its 59 Clauses turned into law with President Asif Ali Zardari’s assent this week, the Supreme Court will effectively no longer judge constitutional cases. There is now a ‘new court’ above it – a constitutional court. The amendment also introduces significant changes to judges’ transfer procedures, the appointment and relief of military officers, and grants nearly unlimited executive powers to the top military leader.

Some on social media question and debate, calling this a ‘soft-return’ of military power in the country, which has spent roughly half its life under various forms of military authority.

Despite continuing protests from opposition, lawyers, and judges, Law Minister Azam Nazir Tarar introduced the bill earlier this week, which creates a new Federal Constitutional Court, gives immunity to some military ranks, and makes Asim Munir more powerful than ever before.

When combined with the 26th Amendment from 2024, this ‘constitutional package’ offers sweeping overhauls to the country's judiciary and military structures.

There are two major reasons for activists, opposition, and people in the judiciary to oppose this Act. 1) diminished judicial powers, 2) an exponential rise in the Executive's role in the judiciary, and massive powers to the military boss.

Pakistan Gets A Special Court For Constitutional Cases

From the historic Kesavananda Bharti case, which gave India its ‘basic structure doctrine’, to the fairly recent landmark hearing in the ‘Electoral Bonds Case’, constitutional cases involve disputes over aspects of a country’s constitution or its interpretation.

Usually, Supreme Courts have been the final word in these disputes in many countries, but now Pakistan has decided to give the burden of justice to the new ‘Federal Constitutional Court of Pakistan’ with its own Chief Justice. Myanmar, Colombia, Germany, Hungary, Indonesia, Thailand, Turkiye, Iraq, and now Pakistan are among the 75+ countries that have a separate Constitutional Court.

So, what’s the harm? Why are lawyers protesting and judges resigning from their posts over the 27th Amendment if other democratic countries also have a separate constitutional court?

Now retired, Judge Mansoor Ali Shah has long opposed the amendment. After its implementation, he resigned in protest, invoking poet Ahmad Faraz’s words against the dictatorial regime of Zia-ul-Haq in an open letter to the country. In it he writes that the 27th Amendment ‘dismantles the Supreme Court of Pakistan, subjugates the judiciary to executive control, and strikes at the very heart of our constitutional democracy – making justice more distant, more fragile, and more vulnerable to power’, later adding, ‘I cannot protect the Constitution, nor can I even judicially examine the amendment that has disfigured it.’

As quoted by Al Jazeera some time before the passing of the amendment, Reema Omer, International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) legal adviser, had said, “The 27th Amendment reduces the Supreme Court of Pakistan to only an appellate court. It is also no longer the ‘Supreme Court of Pakistan’ but only the ‘Supreme Court’ and its chief justice will be the CJ of the SC, not the CJ of Pakistan.”

In several Articles of the Constitution, the word ‘Supreme’ has been replaced with the word ‘Federal Constitutional Court’, including Article 100, which deals with the appointment of the General Attorney of Pakistan, and Article 42, which deals with the President's oath to office.

While all FCC decisions would apply to the Supreme Court, not all Supreme Court decisions would apply to the FCC. Furthermore, all public interest cases pending before the Supreme Court, which are mostly classified as Constitutional, are now transferred to the FCC.

Appointment and Transfer of Judges

Another point of contention is the appointment and transfer of judges.

The first batch of FCC judges has been appointed by the President on the advice of Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif. In the future, the Judicial Commission of Pakistan would be making these appointments, while the chief justice of the FCC would be chosen by a Special Parliamentary Committee. Lawyers in the country, as well as the International Commission of Jurists, point out that the Amendment does not specify appointment criteria, leaving it open to interpretation and potentially enabling favourable postings.

The appointments are of utmost concern, as judges and the CJ of the FCC will be part of the Judicial Commission of Pakistan, which looks after the appointment of other judges, as well as the Supreme Council.

In pre-27th Amendment Pakistan, High Court Judges facing transfers had the option to present a counter-argument if they chose to oppose the transfer order on grounds of logical reasoning. In post-27th Amendment Pakistan, a reference will be filed against the recalcitrant judge before the Supreme Judicial Council, leading to disciplinary action. Additionally, the JCP can recommend the transfer of high court judges to the president and set the conditions for such transfers.

The problem here? Pre-amendment, it was the Chief Justice of Pakistan, along with High Court justices, who made these suggestions to the president, and other judges of the courts where the transfer was taking place had to consent to the transfer. The ICJ points out that Article 200 lacks a clearly defined mechanism and does not explain why the JPC would choose to transfer a judge. Many fear it could become a tool for punitive action against judges not in line with JPC or the government.

Pakistani outlet the Dawn writes, ‘The 27th Amendment fundamentally alters Article 200 of the Constitution of Pakistan, 1973… the removal of the consent requirement and making judges who refuse transfer liable for misconduct proceedings, the provision for transfer now squarely undermines the independence of the judiciary.’

Article 243 and Asim Munir’s Special Position in Pakistan

There were once memes online on how Field Marshal is a ‘purely decorative’ title, but not anymore.

There was once a time when Pakistani military leaders did not enjoy immunity from persecution, but not anymore.

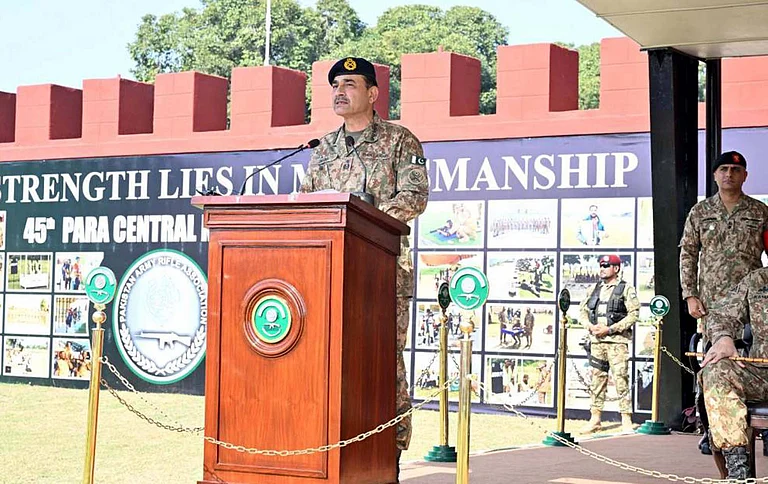

Asim Munir is now the chief of Defence Forces, meaning he is not just the top boss of the army but also of the Navy and Air Force. Along with the new title, he has also become the country’s second-ever Five-Star officer. Luckily for him, the new amendment grants lifelong immunity to all five-star rank officers. Apart from five-star officers (Munir), presidents will now also enjoy lifelong immunity from civil proceedings, unless they are serving in any post-presidency role.

Five-star rank officers, one of whom happens to be Field Marshal Munir, will also keep their ‘rank, privilege, and uniform for life’. So, he shall remain in uniform and be treated as the CDF for the rest of his life.

Asim Munir is (almost) officially above the law in Pakistan. It also blurs the lines in the frequently redrawn and erased lines between the military and government in Pakistan.

ICJ claims that such unconditional immunities only incentivise people to exercise their power arbitrarily.

Defence Minister Khwaja Asif called this amendment a measure ‘to ensure justice’. The Constitutional court, he says, will ensure ‘transparent and swift’ justice, as reported by the Tribune (Pakistan).

While opposition mounts with more protests and resignations, and international media discourse against the Pakistani government intensifies, the Lahore High Court on Tuesday agreed to hear objections to the amendment.

The creation of the FCC, its authority over constitutional matters, and the sweeping powers conferred upon the military command raise essential questions about the future of Pakistan’s judiciary and democracy. As legal challenges move forward, the coming months will test whether checks and balances can truly withstand such transformative change—or if the 27th Amendment’s legacy will be the lasting subordination of Pakistan’s courts to executive and military might.