Sri Lankan director Vimukthi Jayasundara has premiered his latest film at the Busan Film Festival in the inaugural competition

Spying Stars is his new feature in a decade

Starring Indira Tiwari, the sci-fi unfolds in a peculiar daze

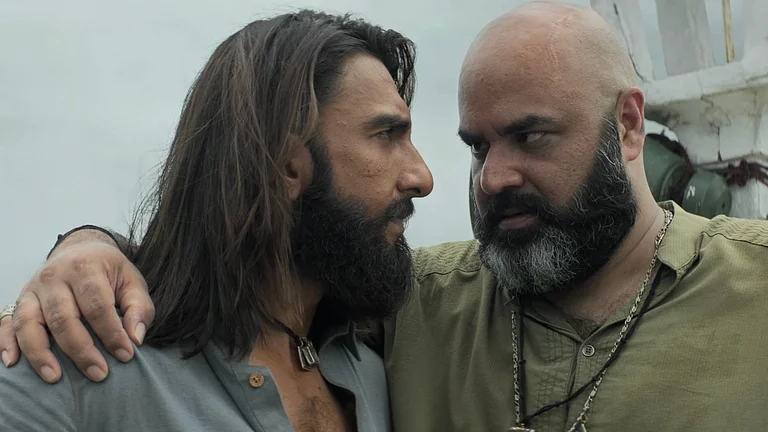

Vimukthi Jayasundara’s latest feature after a decade, Spying Stars, is having its world premiere at the Busan International Film Festival. The film is a disconcerting creation, confounding at times, unwieldy but never complacent. Keeping up with the director’s tendencies, reality in the film is at an accented angle. After years of space research, Sri Lankan scientist Anandi (Indira Tiwari) lands on earth to concede to her father’s final wish. But there’s a catch. The planet has fallen prey to a virus. A machine-driven siege has struck. Reaching Hanuman island, Anandi is shipped off to a quarantine centre while she waits for her late father’s remains.

Jayasundara, one of Sri Lankan cinema’s bold and enduring singular voices, sets up intriguingly. Instead of great establishing lengths, Jayasundara slowly teases glimpses of this strange, fractured new world. A UFO with a fiery glow hovers, surveying everything. On the way to the resort, there are scenes of scuffles. With a ban on electronic devices, analogue has been reprised. The air is rent with peculiar, shrill sounds of animals and birds, none visible. Revelation into the source cracks open a collapse dressed up to distract. Tales of disappearances and brutalities float around.

Right from his debut feature The Forsaken Land (2005) to Between Two Worlds (2009), Jayasundara conjures mystery and existential thudding like an alienating web. Trauma, emotional dislocation and phantom-like humans, set adrift by loss—these recur across the breadth of his oeuvre. Spying Stars is plucked from the same ether. Tiwari seamlessly shifts into Jayasundara’s unique syntax. This is an actor comfortable with any space in its true density, without over-imposing herself. Holding, flitting through, absorbing every place—be it the resort or regulated exteriors—Tiwari plumbs melancholy of still, vast reserves. Haunted by guilt over her father’s passing, Anandi feels severed from human connection. Mostly retreating deep within, her quiet bereavement splays through the screen. Despite the trans resort concierge Nita’s (a striking Hidaayath Hazeer) best efforts, she stays at a remove.

As the satellite looms and encroaches, she struggles to breathe. Sound accentuates the overwhelming unease. Jayasundara piles on the uncanny. An insect that drops dead vibrates so unnervingly, it seems to tear through the world’s artifice. Even flower pots decking the resort have sensory triggers. Sound designer Roman Dymny and Alokananda Dasgupta’s soundtrack build a splitting aural dimension perfectly juxtaposing with the film’s spare sensations. In an unrelenting nightmarish daze, she is clamped down by satellite transmissions that fix the rules of conduct. How will she expand into healing with all the stifling rigidities? Jayasundara invokes an air of deep, forbidding austerity. The island is locked within regimented codes of living. Boundaries are tight, surveillance heaving down at all times. Many of the villagers, though, consider the satellite godsent. It makes you wonder about the degree of human complicity. From being perturbed with violence washing over everywhere to snapping, Anandi takes flight. In Spying Stars, Tiwari does chafe against some of the lines, like a blunt scrap of dialogue when she regrets missing out on the world’s beauty. Tiwari is far more emotionally effective in mute misery. The initial restrained bearing caves to a sense of immense, grueling physical hacking.

This is a drama resisting easy explanations, though, as it winds up, it tries to pave a positive way forward. A note of hope is welcome, but it doesn’t necessarily tide well with the established momentum. It strikes as abrupt, unpersuasive, an odd note within an otherwise compelling, compact film. Spying Stars’ concluding half-hour stretch has a slew of other issues. An important figure is propped up for verbalising themes and anxieties. The watchful cosmos, man-nature osmosis, restorative beckoning to the environment—there’s a lot that jets by. Spying Stars gets too clogged; Jayasundara’s grip doesn’t tally with the ambition. In a haste to tie up threads, the metaphysical elements and a sense of hidden inner reality turn clunkily over-exposed. Jayasundara’s screenplay loses energy and tension in the latter bits. Nita is handed summarily stilted stuff; she explains to Anandi how she always felt there were “two beings stuck inside” her—a constant tussle between the external front of masculinity and inner femininity. It’s as if Jayasundara couldn’t refrain from customarily pronouncing the recycled paradox because he’s introduced a trans character.

Throughout the film, you already encounter the spiritual, human and natural clutching for expression and existence amidst a starkly clinical atmosphere. The quest to know more, invent further has sent the human race into a tailspin. Machines have taken over. But Spying Stars keeps countering with a prevalence of nature—even in the herbs with which Nita lovingly treats Anandi. Eeshit Narain’s camera frames the hills of central Sri Lanka as a space alternating between terrifying bleakness and untapped, unbound beauty. A blue pall draping the visual tone lifts gradually with sunny glare bursting through. Wind-buffeted, characters are always up against defined movements. Jayasundara remains on course as long as he lets Tiwari find equilibrium. In spite of its wavering impulses, this film does exert a peculiar, tantalising grasp.