Summary of this article

The Indian Left has drifted from its core class-based politics, spending much of its energy countering communalism and Hindutva while losing traction among workers and peasants.

Historical misreadings after Independence, ideological splits, and failure to adapt to India’s social realities weakened the Left, creating space for right-wing dominance and neoliberal capitalism.

To revive itself, the Left must unite, diversify its leadership, and reconnect class politics with popular discontent.

‘When things do not go in the right direction, turn left’, used to be the usual jeer against conservative right-wing fellows during our college days. Then it was believed that in Indian politics, the radical Left, or so to say the organised Left, would solve some of the key vexed questions of class, and further, the caste and communal disorders. But over the years, since Independence, its exceptional concern with the menacing growth of communalism on the one hand and the upfront defence of national unity on the other has relegated its core politics of the struggle for economic redistribution of resources and class battles.

With limited political and economic resources at their disposal, and the cultural-Hindutva gatekeepers restraining their initiatives and growth, the Left parties find themselves expending much of their energies fighting the communal politics of hate and fear and less on the questions of the protracted economic battles for the exploited and the oppressed. The Left parties now seem to be warped, in a sense of being besieged, with its own rearguard actions, a sort of forced retreat from its own class politics.

In 1925 at Kanpur, when M.N. Roy laid the foundation of the Communist Party of India (CPI), he extolled the mass movement of poor peasants and workers to liberate themselves from all kinds of exploitation. He had a firm conviction that the party would lead to, through popular upsurges and upheavals, a people’s democratic state and that independent India would be free from landlordism and land given to the tiller. The autocracy would be abolished and key industries would be nationalised with a living wage.

The communists, during the freedom struggle, however, quite often misread social disturbances as insurrections, failed to grasp the people’s willingness to fight and their continuing repositioning of faith with the Congress as the leader of the national movement, and refused to accept Indian Independence as the real Independence. For them, the transfer of power was an unacceptable compromise at the hands of a nationalist leadership, and the newly independent state a satellite state dependent on imperialism. India, they explained, would continue as a colony and, therefore, would be ruled by the ‘imperialist-bourgeois-feudal’ combine.

Why is the Left not able to find counter-strategies and tactics to gain traction with the peasantry and working class?

The idea of striking at the state power and wage a liberation struggle got traction with the early communists, famously known as the Ranadive line—the line accepted in the second congress of the party held in Calcutta (1948) with B.T. Ranadive as the General Secretary. However, within the communist party, differences emerged on the role of the party’s method in laying mass struggles—a strong Ranadive line was for a revolutionary insurrection on the lines of the Russian Revolution, an assessment of the bourgeoisie—whether they were playing the dual role of collaborator and opposition vis-a-vis imperialism—and the possibility of integration of global contradictions in Indian society. The Left couldn’t fathom, at the time of Independence, the ‘stage of development in society’ and presumed it to be a part of global sea change occurring particularly in China, Vietnam, Korea and the then USSR. Calling the Indian state a ‘satellite state’ and its rulers as ‘stooges’, not paying attention to Indian monopoly capital which tried to use state power to occupy the economic space left free by the withdrawal of imperialism (Bombay Plan, 1946), and lack of clarity in the party’s programme as to how capitalism, or, for that matter, communism, would be structured and processed vis-à-vis social relations, were perhaps some of the gross errors the Left committed in the initial years of its functioning.

Left in Contemporary Times of Turbulence

The most formidable question in Indian politics today, or perhaps since the rise of three Ms—Mandal, Mandir-Masjid, Market—relating to the rise of right-wing Hindutva and the Modi government is: what does it portend for Left parties, including socialists, feminists and anti-casteist groups, seeking to oppose the present government and Hindutva in general?

Hindutva, as we all know, has stormed to power on episodic waves due to its potential for irrational and violent political mobilisation. It has advanced at a time when we see the long-term decline of the Congress and the Left parties and the rise of regional parties, which are run by the state’s local dominant caste-propertied groups. Since 2014, the Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP) has captured the popular imagination of the Indian political discourse, essentially with its three components, as Yogendra Yadav points out—one, its brute centralised power through unconstitutional elements and para-state forces, two, its ‘electoral dominance’, though the whole legitimacy and fairness of the electoral process is questioned by the Opposition and, three, the ‘moral and ideological acceptance of the regime by the people’. The regime has, above all, facilitated the accumulation process of private capital, which has resulted in an enormous disparity, particularly in consumption, despite the fact that the economy is supposed to thrive on the idea of consumption. There have emerged, therefore, two serious crises—the accumulation crisis and the consumption crisis.

What is the way forward in such difficult times for the Left? Why is the Left not able to find counter-strategies and tactics to gain traction with the peasantry and working class? After the defeat of the Communist Party of India-Marxist (CPI-M) in West Bengal (2011), there was a palpable sense of despair that perhaps it was the end of the Left in India and many on the side of the Left felt that the defeat has not only weakened the Left movement, but also created space for right-wing forces. Some, nonetheless, felt that the space created due to their defeat should mean space for a stronger Left, a new Left with a new imagination and praxis. The crisis of the Left is the crisis in its splits, the first in 1964 in the backdrop of Sino-Soviet rivalry, which led to the formation of the CPI(M). It is time now for the Left to look forward to regrouping and mergers of the Left parties, and to forge a Left unity for parliamentary politics.

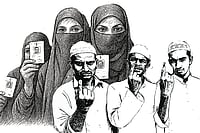

The Left needs to envision the new spaces that capitalism, in its neoliberal avatar, innocuously opens up as it progresses towards more inhuman, callous and inconsiderate socio-economic conditions, albeit with more sophisticated means. Left leaders must focus on corruption, transparency and other significant accountability issues of democracy and take them to the people with simple explanations. It is high time for the Left to capture the discontent brewing in society in the name of populism and stitch people’s aspirations to its core idea of transforming society for a better living condition for the poor masses, particularly of the working class. The Indian Left needs a fresh discourse on ways to solve caste and communal conflicts and not to fall prey to identity politics. It has been alleged, and rightly so, that its leadership comes from upper-caste-elite Hindus, and generally males—another significant reason for its lack of appeal to a large swathe of the masses belonging to the working-class people, who are mostly not the upper-caste-elite Hindus. It must reach out to Muslims afresh, keeping in mind that the majority of them are looking for a party other than the BJP, that can give them a sense of security and better livelihood opportunities.

The absence of Dalits and Muslims in its leadership roles may not augur well for the Left parties in its fight for caste and communal equality. The Left needs to locate identity politics within a class-based transcendental politics. And lastly, it needs to reinvent its organisational practice by de-heirarchizing itself in its larger battle against neoliberal capitalism.

(Views expressed are personal)

Tanvir Aeijaz teaches politics and public policy at the University Of Delhi and is Hon. Vice-Chairman and member secretary at the centre for multilevel federalism, Institute Of Social Sciences, New Delhi.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

This article appeared as Minimum Marxism in Outlook’s December 21, 2025, issue as 'What's Left of the Left' which explores how the Left finds itself at an interesting and challenging crossroad now the Left needs to adapt. And perhaps it will do so.