Summary of this article

Ambedkar accused communists of ignoring caste while CPI sought to dilute his influence.

Critics say Savarna-led Left long sidelined caste, pushing class over social oppression.

Late representational shifts expose ideological limits that haunt the modern Left.

Bhimrao Babasaheb Ambedkar never minced words.

For him, the Indian communist leadership was a circle of “Brahmin boys”, unable or unwilling to grasp the daily violence of caste. The communists, in turn, accused Ambedkar of siding with imperial interests and holding back the so-called untouchable masses from the wider democratic struggle.

The clash sharpened in 1952. After leading the Independent Labour Party (ILP), Ambedkar founded the Scheduled Caste Federation (SCF), shifting focus to specifically champion Dalit rights as a national political force, evolving from the ILP’s broader labour and anti-caste work into a platform dedicated solely to Scheduled Caste interests. The ILP was Ambedkar’s first political vehicle to address general labour rights and anti-caste issues. The SCF was formed to secure a distinct political platform to secure the rights of the Dalits.

Soon after, the Communist Party of India’s (CPI) central committee passed a resolution urging cadres to break Ambedkar’s influence among Dalits by taking up their demands and leading the fight against caste-Hindu oppression through common mass organisations. The resolution stated: “The party must sharply expose the policies of Ambedkar and wean the SCF masses away from his influence by boldly championing the democratic demands of the Scheduled Caste masses, by fighting caste-Hindu oppression against them and by drawing them into common mass organisations.”

Rooted in a classical Marxist framework, Indian communists largely saw caste as a secondary contradiction, something that would ultimately be resolved and subsumed within the broader context of class struggle. Yet, despite ideologically relegating caste to a lesser plane, it continues to haunt the Indian communist movement, especially after the Mandal era, which changed the Indian political landscape without recognition.

Constitutional expert and former director of the National Law School of India, Mohan Gopal, argues that the Indian communist leadership’s longstanding discomfort with the anti-caste movement is rooted in its Savarna social orientation. To illustrate this, he cites Left ideologue EMS Namboodiripad. When Namboodiripad was invited to inaugurate a programme at Shivagiri on the birth anniversary of social reformer Sri Narayana Guru, he declined. Gopal notes that EMS reportedly justified his refusal by saying that if he had attended, he would have been expected to acknowledge Guru’s historical contributions, “which he did not like”.

For Gopal, this episode captures a deeper pattern: a reluctance within sections of the communist leadership to recognise, let alone celebrate, the transformative role of anti-caste reformers. In his view, this reflects not merely ideological differences but a structural inability on the part of a Savarna-dominated leadership to engage fully with the politics of caste emancipation. The Indian Communist Party leadership’s caste elite domination has been pointed out by many as its inability to confront caste as a social reality.

“Caste was never brought as a subject that merits discussion within our organisation,” says O.K. Santhosh, professor at the University of Madras. Santhosh was a Students’ Federation of India (SFI) leader, a senate member, and a college union chairman in his college days. “In our committees, we used to discuss about liberalisation, privatisation and globalisation and a whole lot of things. But never caste issues. I don’t think it is deliberate. But growing up, I found the party’s approach inadequate to explain social realities and moved towards Ambedkarite movements,” he said.

C.K. Janu, a firebrand tribal leader, began her public life through the CPIM-led agricultural workers’ front, the Kerala Karshaka Thozhilali Union (KSKTU). She says the party and its leaders were impervious to the demands arising from the systemic issues tribals faced, such as landlessness and marginalisation. “Whenever I tried to present the case of the tribes, their problems and the ill-treatment meted out by the people who owned large swathes of land, it was given a short shrift. We were forced to form a tribal association—the Adivasi Gothra Mahasabha—because of the Left’s approach towards the tribals. They used us only for political processions and to stick posters,” she said.

A CPI(M) sympathiser, who did not wish to be identified, pointed to an interview given by former general secretary, the late Sitaram Yechury, to illustrate what he sees as the Left’s deeper ideological blind spot on caste. In that interview, Yechury recalled an exchange with the late Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) founder Kanshi Ram. Kanshi Ram had asked him a seemingly simple question: How many Dalits are there in the West Bengal CPI(M) cabinet? Yechury admitted that he did not know and promised to check.

The sympathiser highlighted that even a close associate of Yechury—a CPI(M) minister—did not know the social background of his own colleague. Within the party culture, he said, “to be innocent of caste was regarded as a sign of ideological purity.” What is often celebrated as caste-blindness, he argued, is not an individual failing but a structural limitation of the Left’s ideological framework, which discourages acknowledging caste as a political reality even when it shapes access to power.

In 1989, when the VP Singh government announced the implementation of the Mandal Commission report, the Left’s vote share was at its highest, with the CPI (M) at 6.55 per cent and the CPI at 2.57 per cent. But the political decision that catapulted parties with a social justice agenda also sidelined the Left. Except in 2004, when the Left was instrumental in propping up the United Progressive Alliance government, its role has waned since then. Dalit thinkers argue that the cultural and identity-centred dimensions of social oppression, especially caste, were systematically sidelined in communist practice, even as anti-caste movements outside the Left dramatically reshaped India’s social landscape.

Interestingly, even intellectuals within the communist fold now acknowledge that this neglect may be central to the crisis the Left faces today. “The caste background of the earlier leaders could be one reason for not taking the caste issue seriously,” says Saira Shah Halim, author of Comrades and Comebacks. She notes that communist parties failed to recognise caste as a primary structure of oppression and instead relied almost exclusively on economic explanations. “They pushed the base-superstructure theory, believing that once the economic structure was corrected, every other social problem, including caste oppression, would disappear. That approach is deeply flawed,” she adds.

The Communist Party’s approach to identity politics is reflected starkly in the social composition of its leadership. For 58 years after its formation in 1964, the CPI(M) did not have a single Dalit member in its Politburo. It was only at the 2022 Party Congress that Ramachandra Dome, a Dalit leader from West Bengal, was inducted into the party’s highest decision-making body. The 2025 Congress added another leader from a marginalised community, Jitendra Chowdhury, a tribal leader from Tripura. The CPI, India’s oldest communist party, now has a Dalit general secretary in D. Raja, marking a late but notable shift in representational politics.

Engaging with caste has remained a persistent fault line in Indian politics, with Ambedkar on one side and nearly every other political formation, each in its own way, on the other. The communist approach, and its limitations, appear more pronounced because the Left explicitly claims a revolutionary mandate to abolish all classes. This makes its difficulty in fully grappling with caste even more glaring.

The question of how social markers such as caste and gender fit into the Left’s overarching class narrative is therefore unlikely to fade. In all likelihood, the Left will continue to animate political and intellectual debates, perhaps until both caste and class hierarchies are dismantled.

N.K. Bhoopesh is an assistant editor, reporting on South India with a focus on politics, developmental challenges, and stories rooted in social justice

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

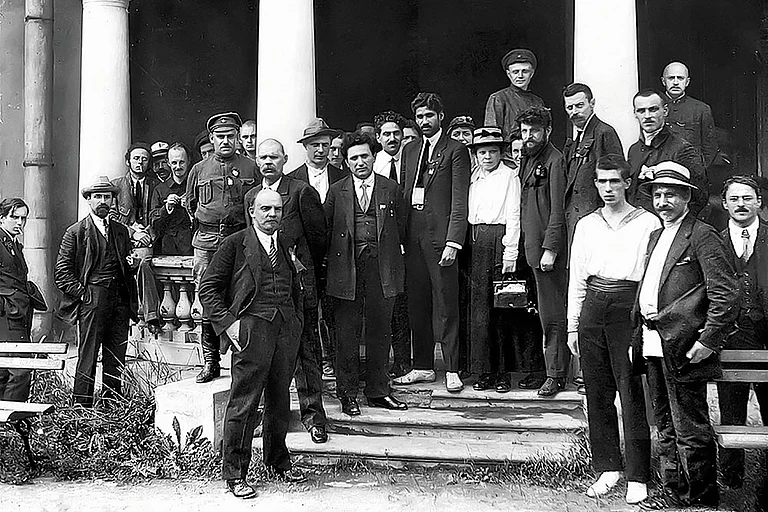

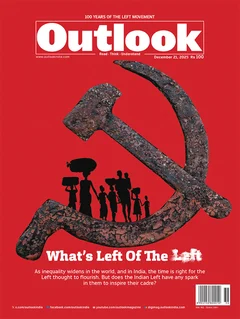

This article appeared as Reportage On Blind Spots Left Is Countering Ambedkar And The ‘Brahmin Boys’ in Outlook’s December 21, 2025, issue as 'What's Left of the Left' which explores the challenging crossroads the Left finds itself at and how they need to adapt. And perhaps it will do so.