Once a devoted swayamsevak, Bhanwar Meghwanshi left the RSS after facing caste discrimination, exposing the organisation’s deep-rooted Brahminical hierarchy.

He argues that Hindutva and caste are inseparable, calling the RSS’s attempts at “social harmony” mere tokenism.

He sees hope in young Dalits using literature, social media, and activism to challenge caste oppression

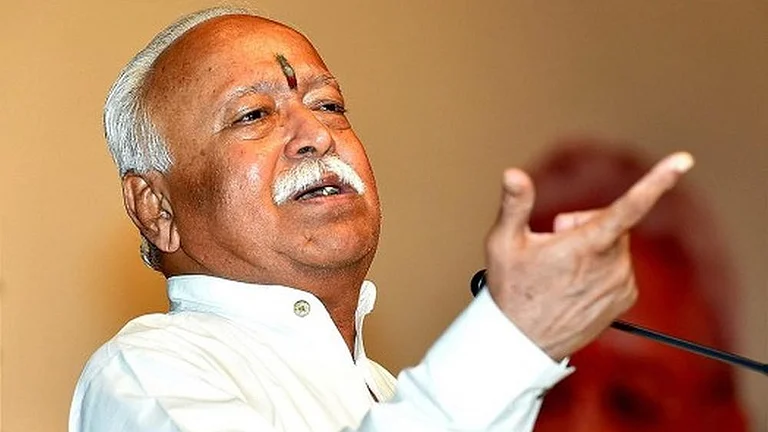

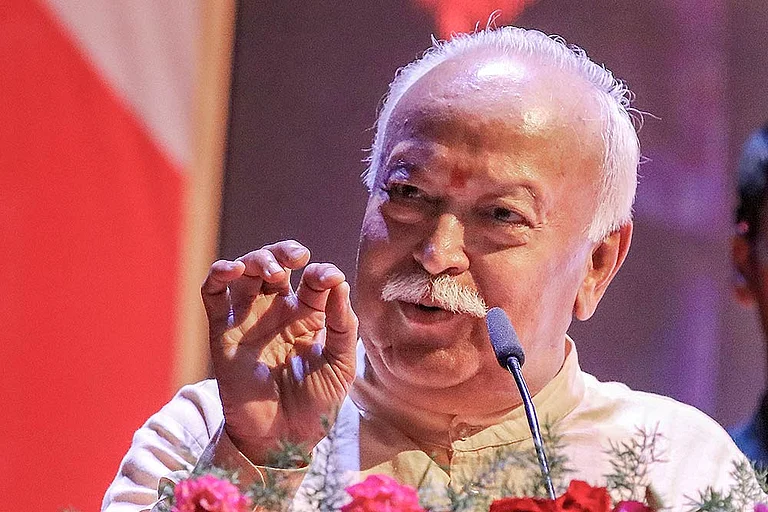

Bhanwar Meghwanshi is a social activist, journalist and writer. He joined the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) during his teenage years and rose in the organisation’s ranks. During the Babri Masjid demolition movement, he joined the karsevaks to go to Ayodhya. His arrest became a turning point of his life, prompting him to question the RSS’ casteist realities, and eventually leave the organisation. He founded platforms such as Diamond India, Khabarkosh and Shoonyakaal to amplify marginalised voices. He has also worked with the Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan and played an important role in implementing laws such as RTI, NREGA and the Food Security Act. His book I Could Not Be Hindu (originally written in Hindi as Main Ek Kar Sevak Tha) has been translated into multiple languages. Meghwanshi spoke to Jagisha Arora about his eventful journey. Excerpts:

In your book I Could Not Be Hindu, you share your journey from being part of the RSS to questioning its casteist foundations. What was the turning point that made you step away from the organisation?

In my book, I have explained the caste-based structure that exists within the RSS. While the RSS claims to transcend caste and unite all Hindus, my experience revealed a completely different truth. Dalits, I found, are used merely as foot soldiers and they are pushed to fight for the interests of upper-caste Hindus while their own identity and dignity remain unacknowledged. When Dalit volunteers first join the shakhas, there’s a superficial display of respect but beneath it, the Brahminical hierarchy persists and Dalits are systematically kept away from leadership roles. I personally faced caste discrimination several times, but the turning point came in 1991. In my village, Sidhiyas in Bhilwara district, senior RSS members refused to eat food prepared in my home. They had it packed and carried to another village, only to throw it by the roadside. It happened simply because I was a Dalit.

I immediately lodged complaints at every level, even writing to the then Sarsanghchalak in Nagpur but no one cared to respond. That silence, that refusal to hear my pain, laid bare the hypocrisy of the organisation. That’s when I decided to leave the RSS.

You’ve written about your own recruitment into the Sangh in your youth. How do you see the RSS adapting its methods today to appeal to Gen Z?

As you know, in most public spaces across the Hindi-speaking belt, the RSS has established itself in the name of sports, physical training and nationalist slogans. During my teenage years, such activities fascinated me and during my growing years, there was no television for everyone and mobile phones didn’t exist.

But today, we live in the age of digital communication. The generation has changed. The shorts we once wore to the shakha have been replaced by khaki trousers to suit modern sensibilities. And in this era of social media, the RSS even conducts ‘online shakhas’. To attract Gen Z and Gen Alpha, they’re fully exploiting digital platforms and using short videos, memes and campaigns to spread Hindutva. They provoke young people—urban and rural, upper-caste and Dalit-OBC in the name of ‘Hindu unity’. Compared to my time, their outreach is much more powerful today because digital media allows them to penetrate deep and fast. Yet, I believe this change is only cosmetic because casteism remains hidden. They’re turning youth into cannon fodder for a Hindu Rashtra without addressing their demands for social justice and this won’t sustain for long.

Many Dalits continue to face caste-based discrimination. From your lived experience, where do you think India has failed most in addressing caste oppression?

India’s biggest failure in eliminating caste-based untouchability, exploitation, and violence is most visible in rural areas where Dalits still face social and economic boycotts and brutal atrocities. From my experience, even though laws like the SC/ST Act exist, the police and administration often side with the upper castes. As a result, cases go unregistered or are quietly ‘settled’ under the guise of investigation. In today’s political climate, where majoritarian politics views Dalits merely as a vote bank, genuine transformation seems impossible.

Organisations like the RSS pretend to promote ‘harmony’, but in truth, they maintain the caste hierarchy. There is no path to liberation for Dalits within Hindutva. Real change will come only when Dalits, with ideological clarity, organise themselves and fight for their own emancipation.

You often talked about the role of lived experience in shaping political consciousness. How important is storytelling and memoir in the fight against caste?

Storytelllng and memoirs play a vital role in the fight against caste. Through personal experiences, they expose uncomfortable truths and awaken political consciousness. Whether it’s the autobiography of former RSS pracharak Sudhish Minni, the writings of Mulchand Rana (former Gujarat Public Service Commission member once associated with the Samrasta Manch), or my own book, all reveal the casteism deeply embedded within the RSS.

Such narratives are far more powerful than statistics. They inspire Dalits to recognise their identity and struggle, while confronting casteist upper castes with their complicity. Dr. B.R. Ambedkar did the same as he transformed personal pain into a social movement. Stories have wings as they travel far and wide. India is a land that believes in stories and people may dismiss facts and figures, but they rarely deny the power of a lived narrative.

Your book delves into casteism within Hindu nationalist organisations. Do you think these organisations have changed their approach toward Dalits in recent years, or is it still tokenism?

I would like to say that in my viewpoint, casteism still runs deep within the Hindu nationalist organisations. Though their top leadership may publicly denounce casteism and express support for reservations, they do all of these for the sake of optics and political correctness. While their grassroots cadre continues to hold the same anti-Dalit and anti-reservation mindset. In recent years, they’ve made superficial gestures. For instance: “Samrasta Abhiyan” or showing support for reservations but these are hollow. Their only ambition is to confuse Dalits and use them to strengthen Hindutva, while leadership positions remain dominated by Brahmins.

In 2014, the RSS appointed its first OBC, V. Bhagaya as one of its six top functionaries. In 2015, the organisation directed offices to display portraits of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar. These moves were politically motivated and not ideological as they sought to secure Dalit, OBC, and Adivasi votes. Beneath this façade, their leadership remains overwhelmingly upper caste. My own experience tells me that calling Dalits “the deprived” is a tactic to erase their distinct identity and to keep the varna system intact, to destroy Dalit consciousness, and to turn them into religious subordinates.

You write about the pain of betrayal when realising the contradictions within Hindutva politics. How did that personal disillusionment shape your activism today?

Understanding the contradictions within Hindutva politics deepens the pain of betrayal. For me, the moment of disillusionment from the incident when my food was thrown away which exposed the Brahminical nature of the RSS. After that, I turned to Ambedkar’s writings, embraced his teachings and philosophy and became an activist in the Dalit movement. Even today, through my writing and activism, I continue to fight for social justice. The caste discrimination I experienced during my time in the organisation helped me recognise the hypocrisy of Hindutva, and in this process, the Ambedkarite thought gave me the strength to understand the nuances and later expose it.

Dalit assertion has taken new forms. For instance: literature, social media, grassroots activism and movements. What role do you see young Dalits playing in transforming Indian society?

A new consciousness is emerging within the Dalit community which is through literature, social media, grassroots activism, and new forms of movements. Today’s Dalit youth are revolutionary as they are fearlessly exposing casteism whether on the streets and online and telling their stories through art and writing, and pushing for social transformation through collective action. As they all are inspired by Dr. Ambedkar’s vision and they are uniting, and I truly believe they will play a crucial role in making Indian society caste-free.

Do you think the RSS has genuinely changed its stance on caste in recent years, or is it more of a political move?

The RSS’ occasional change in tone on caste is nothing but an annual shedding of skin which is like a snake changing its scales. The core ideology remains untouched. Hindutva is inseparable from caste. Can Hinduism exist without hierarchy and inequality? Do they ever challenge their own scriptures that sanctify caste? Do they actively promote inter-caste marriages? The answer is no. Instead, they turn the constitutional promise of equality into the sweet poison of “samrasta” (harmony), manipulating language to turn Dalits into their vote bank. The RSS remains a purely Brahminical organisation--of its 7 chiefs so far, 6 (except Rajju Bhaiya) have been Brahmins. Their ideology rests on caste superiority. Therefore, caste annihilation from within the RSS is impossible. Their idea of a Hindu Rashtra depends on the varna system. The battle against it must come from outside and the Ambedkarite movement remains the most powerful force to fight it.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

This article appeared in Outlook Magazine's 21 October Edition 'Who Is An Indian?' as One Hundred Years Of...Being A Lesser Hindu.