This article is a part of the column Retro Express, exploring court dramas across the years.

It includes discussions on films including Shehenshah (1988), Waqt (1965), Meri Jung (1985) and more.

The article asks several questions, including if representation and authenticity in courtroom dramas improved over the last few decades.

A few years ago, I was witness to the unfolding of the Johnny Depp vs Amber Heard drama on live TV while in the US, and the first thing that struck me was how sparse and clinical the court room looked, and yet how glamorous was Depp’s lawyer Camille Vasquez. I remember noticing how high her heels were and that if she had to be in a Hindi movie, she probably wouldn’t have worn them because lawyers in Hindi movies often walked about in a theatrical flourish across the width of the courtroom. I believed that is how they argued, until I saw a real courtroom, where there was barely any room to stand for the most part, forget walking about.

In Hindi cinema, courtrooms have always been stages for intense emotional outbursts, shouting matches, and miraculous last-minute evidence, not dry defamation proceedings like Heard vs Depp, glamorous lawyer notwithstanding.

Before I knew better, I always imagined Indian courts as royal spaces, as though they were lesser versions of grand palaces: lavish, well-polished tables for judges, two guards to escort them to and from their desk, and a court full of people rooting for each side. Lawyers (often the hero) delivered powerful, emotional speeches, fighting for truth and justice against overwhelming odds, making it a central plot point. There were grand exposures and grander decisions. And of course, dramatic, heavy usage of Urdu to address the main players: mere kaabil dost, tehet, muvakkil, mulzim/mulzima etc. or the flamboyant utterances of Tazirat-e-Hind, and Sazaye-Maut.

Judges in Bollywood movies had a limited vocabulary of “Order, Order!”, “Objection overruled" and “Sustained”. In reality, the judge is the most active participant in the proceedings, asking pointed questions frequently, and even scolding/rebuking the lawyers if they have made a mistake or not followed the rules. And he doesn’t need an “Order, order!” to be taken seriously. There is no gavel banging, often no space on the judge’s desk for a gavel. Lawyers are often not good orators, documents are often misplaced and there is a lot of fumbling, and arguments are mostly technical and devoid of story-telling.

The classic scene of a witness swearing on the Bhagavad Gita (or other holy books) with their hand on it, while in the witness box (katghara) is another strategic element, even if the said witness has murdered and plundered a few scenes ago. As for what can happen in court, nothing is off limits.

In Meri Jung (1985), Anil Kapoor, who plays a lawyer, downs a full bottle of medicine in court only to prove that it is not, in fact, poison, and that his client did not poison the bottle. Of course, his friend is waiting right outside court to take him to a clinic for a purge soon after this dramatic consumption, and since he is the hero, he survives this near-death experience.

In Shahenshah (1988), Amrish Puri ends up in court accused of murdering Amitabh Bachchan’s brother-in-law. A witness claims Bachchan got a confession at gunpoint, which Bachchan denies. The lawyer then picks up a gun, points to the judge and says “Admit you are the murderer, else I will shoot you.” The judge admits. The lawyer laughs and says my point is proven. The judge lets Puri go. In the same film, Bachchan drives an old woman, the only witness in the case, to court...rather, inside the court, breaking its walls, to be precise. The dramatic entry is warranted by the fact that on his way to the court, he is attacked by goons with machine guns.

The 1993 film Damini shows Sunny Deol as a hot-blooded lawyer who fights for justice for a gang rape victim. Deol made courtrooms cool again with his tareekh pe tareekh dialogue, which is still used in contexts outside of court. In the same movie, Damini (Meenakshi Seshadri) is asked by the defence lawyer Amrish Puri to identify the four rapists from a group of men, whose faces are covered in Holi colours (this is an important plot line in the movie). Puri then ups the drama by pushing each man upon Damini, trying to provoke her to make a point.

The polar opposite, Chaitanya Tamhane’s 2015 movie Court, is as real as it gets about how soul-sapping a court case can be and how the plaintiff’s interest is the last thing on anyone’s mind. When a lawyer reads out a lengthy statement about a case, her voice is as inexpressive and bored, as Deol’s or Puri’s were loud and emotion-drenched.

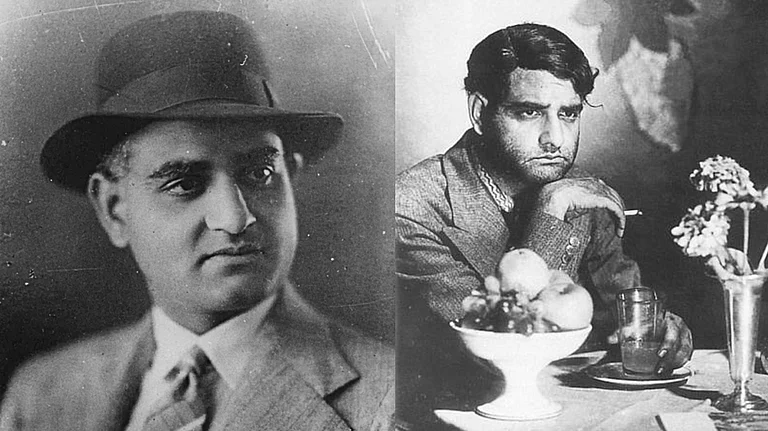

In the black and white era, court rooms seemed even more dramatic. BR Chopra’s Kanoon (1960), a suspense thriller starring Ashok Kumar, Rajendra Kumar and Nanda, is a film that highlights the aberrations of the judicial system. The film, in which a judge is accused and discharged of murder, is replete with long monologues and mood lighting.

The 1963 film Yeh Rastey Hain Pyar Ke, directed by R.K. Nayyar, was based on the famous K.M. Nanavati trial, about a naval commander who was tried for the murder of his wife’s paramour in 1959. But unlike the real life case, we find that the wife (Leela Naidu) isn’t really an adulteress and her drink was spiked by her husband’s best friend (Rehman) to score, but she still has to feel defiled and be the suffering martyr and, surprise surprise—the actual killer is not really the husband (Sunil Dutt). This diluting of the real life case makes it look like the filmmakers developed cold feet and got scared to go the whole way, keeping in mind the moralities prevalent in 1963. But the court dynamic between Ashok Kumar and Motilal (defense and prosecution lawyers) is what made the film watchable.

In BR Chopra’s multi-starrer Waqt (1965), Balraj Sahni’s family, thrown asunder by nothing less than an earthquake, is reunited against the backdrop of a murder trial in court. The kachehri scenes clearly serve much drama in this already over-dramatised plot.

Movies like Pink (2016), Jolly LLB (2013 -2025) or even Court offer a more realistic portrayal of courts, not veering towards the excesses of movies from other decades. Here, files of various cases are shown piling on cupboards and tables. The judges enjoy more humble seating, and the courtroom follows a more suitable setting, the legalese is mechanical and devoid of drama, people are sweat-soaked, court rooms are not as well-lit and there are no grand entries, exits or gestures.

Most of the times, when I have been in court, I have been waiting for a judge to make a grand entry, with a suitable announcement. However, the entries (and the judges themselves) have been most unspectacular, leaving me disappointed. The ‘all rise’, however, is still a thing, although more implied than stated.

While I don’t want court scenes in Hindi cinema to suddenly become drab and paperwork-laden—we go to the movies for escapism, after all—a little honesty wouldn’t hurt. Courtrooms don’t need Bachchan crashing through walls or lawyers delivering death-defying demonstrations to keep us invested. The tension in real legal battles lies not in flying bullets or gavels but in the quiet ticking of time, the sheer weight of what is at stake, and the frustratingly human flaws of a system meant to uphold justice. At the end of the day milord, truth is drama enough.