Summary of this article

Twenty-five years in, LeftWord shows how Left publishing in India has resisted erasure through dissent and solidarity in a right-wing climate.

By backing its backlist and building alternative distribution networks, LeftWord pushes against market-driven silence in publishing.

Feminist and regional presses alongside LeftWord keep political truth alive, even when telling it comes at a cost.

Recently, I found myself absorbed in Stranger in My Own Land – written by Farid Khan and translated into English by Jerry Pinto - a book that lays bare what it means to feel alienated in the very place you call home. “It is my experience that when a mobile phone rings on a train, no one uses the greeting ‘Salaam’ anymore. Not in a railway compartment,” writes Khan. The line made me feel the weight of everyday silences — the kind the author calls “as real as the pinch of a new shoe.”

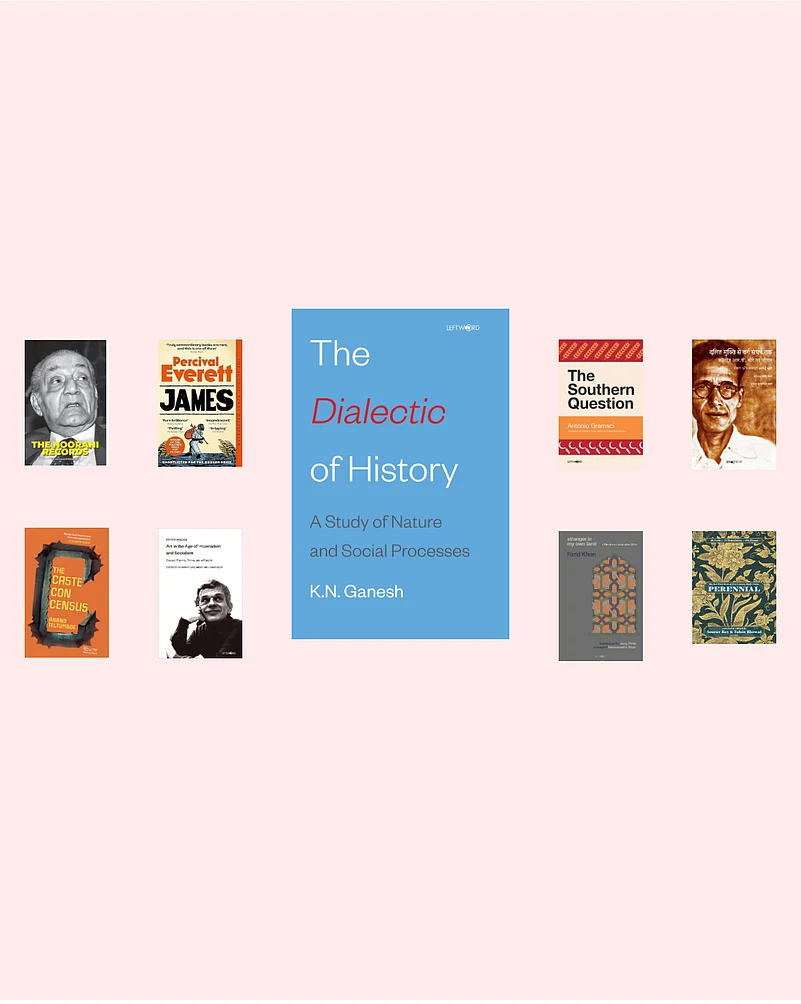

It reminded me of how literature can insist on memory — refusing erasure, documenting lived experience, and demanding accountability. That urgency, to record and resist, is what drives LeftWord Books, a press that has long published stories and ideas that push back against silence and amnesia. One of the most important Marxist publishing houses in the world, whose authors have included Marxist scholar Aijaz Ahmad, editor N Ram, and lawyer Teesta Setalvad, LeftWord is 25 years old in India, and a crucial home for voices of resistance—publishing labour histories, anti-capitalist thought, and narratives of struggle that rarely find space in mainstream Indian publishing.

Sudhanva Deshpande, theatre maker and managing editor of LeftWord books, reflects on how the Left speaks to the moment we are living through: “Well, in this hostile atmosphere, it is all the more important and urgent to keep publishing voices of reason and rationality, with a progressive and secular outlook, and to amplify voices from the margins. So far at least, we've not had to pull back from publishing anything we've wanted to, but yes, we are more alert to potential issues. Some of our authors have been targeted in various ways, including by being incarcerated under grave – and completely unfounded – charges. Especially in such cases, we feel it is our duty to make their books available to as many readers as possible, so that their ideas can circulate widely.”

Speaking of the recent success of the Hindi translation of Romila Thapar's Our History, Their History, Whose History?(Hamara Itihas, Unka Itihas, Kiska Itihas?), he reveals that Prof. Thapar herself was pleasantly surprised that the Hindi version made much more of a splash than the English (published by one of the top independent publishers, Seagull Books, from Kolkata).

But it is not often that a book does well immediately on its release, so how does one ensure longevity for Left titles and ensure they travel and speak to many minds? “Actually, one of the problems of the new trends in publishing is the overbearing importance given to new releases and the front list, to the detriment of the mid- and backlist. There is a great pressure on books to do well immediately after release, because soon they're going to be forgotten by the marketing department, and copies will languish forlornly at the back of godowns till they are pulped. At LeftWord, we don't have this approach. We are proud of our mid- and backlist, and we do all we can to promote these and keep bringing them back to readers' attention. Our backlist is strong and contributes substantially to our revenues,” says Deshpande.

Kali for Women, India's first and oldest feminist press, was co-founded by Ritu Menon in 1984. She is a publisher and writer who has spent decades making feminist publishing central to India’s literary landscape and has written extensively on women and religion; women and violence; women in situations of armed conflict; and on the gendering of citizenship, through her work on women and the nation. What about the current moment feels most urgent — and what still hasn’t changed enough, I ask her:

“There’s a saying in Chinese that working towards social change is like taking two steps forward, one step back. I think we’re in the one step back phase. The rise of right-wing conservatism across the world, and certainly here, is almost always accompanied by resurgent patriarchies and hypermasculinism. That can never be good for women as a whole. This to me is an urgent preoccupation.”

But for Left literature to be discoverable and accessible, many movements have to work in tandem. LeftWord, for instance, has co-founded a distribution initiative, the Independent Publishers' Distribution Alternative (IPDA), that takes books from a bouquet of independent and small publishers to the market. They have also co-founded another exciting initiative, India Independent: Books and Ideas (IIBA), along with eight other publishing and bookselling professionals. IIBA conceptualises alternative book fairs, new platforms for ideas, and an online portal to bring together physical (i.e., bricks and mortar) independent bookstores, a kind of online bookstore of bookstores. Deshpande explains, “At LeftWord, we've worked for a long time with other independent presses to seek alliances and synergies. At our own store in Delhi, the May Day Bookstore, we do a bunch of activities that draw readers, especially young people. And we were one of the early publishers to take to online selling – we created our first website back in 2001, when there were no smartphones, and most people didn't even have credit cards (and those who did, were wary of using them online). We're also part of networks of left publishers in India and internationally, through which we've been promoting the idea of reciprocal 'solidarity rights sharing' as an alternative to profit-driven rights' sales. On the whole, we believe that small and independent presses and bookstores have to work together and build our collective strength.

Gita Ramaswamy, who runs Hyderabad Book Trust and has worked extensively in left-leaning Telugu language publishing for over four decades, responds to “political costs” of telling the truth in print today and what independence means to her as an editor with a political mandate. “Don’t let people tell you that there are political costs of telling the truth in print. Those who respond affirmatively are those who worry about their shareholder dividends and personal needs, like sponsored junkets abroad, government permission to house expansion and admissions to Ivy League institutions abroad for their children. For aam janata like us, there are no political costs. Yes, when we printed the Gujarat 2002 genocide books in Telugu, we worried that the Hindutva brigade would destroy our office. But we figured that even this would rally support for the cause,” she says.

Some of their titles include David Werner's Where There is no Doctor, I, Phoolan Devi by Phoolan Devi, The Menace of Hindu Imperialism by Swami Dharma Tirtha, Debrahmanising History: Dominance and Resistance in Indian Society by Braj Ranjan Mani, My Years in an Indian Prison by Mary Tyler, Why I am Not a Hindu by Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd, all in translation.

In a climate where silence is often rewarded, and dissent can come at a personal cost, these publishers and many more like them continue to insist on speaking and printing the truth. Their catalogues are not just collections of books but archives of resistance, repositories of historical memory, and reminders that democratic debate does not belong to those in power alone. As Deshpande points out, LeftWord’s backlist itself is a measure of its endurance and impact, and voices like Ritu Menon and Gita Ramaswamy show how feminist and regional presses have built their own infrastructures of courage. What emerges is a network of independent publishers pushing back, collaborating, inventing alternatives, and refusing erasure. The Left is not merely surviving in Indian publishing — it continues to lead the conversation on who gets to be seen, heard, and remembered.

In Indian publishing, the Left does not just live on — it insists on being read.