Summary of this article

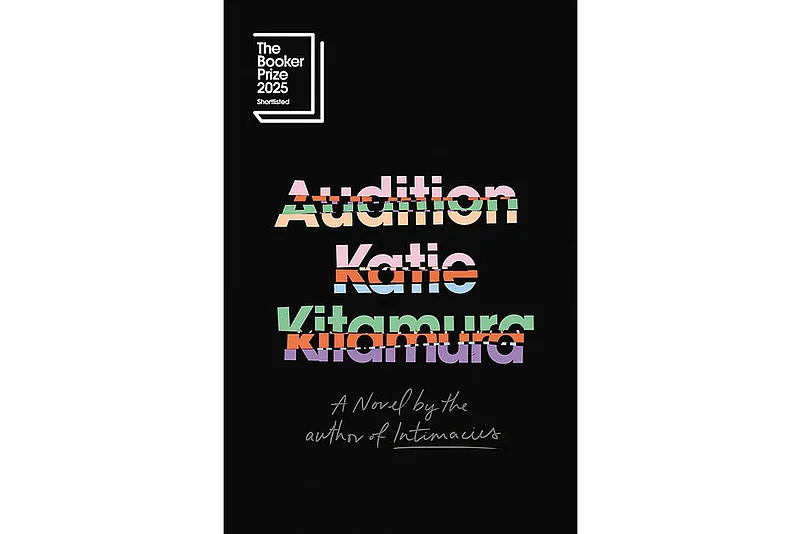

A middle-aged actress’s life unravels when a young man claims to be her son.

Reality, performance and desire blur through shifting truths and role-play.

Kitamura delivers a cold, controlled psychodrama that resists certainty.

In Katie Kitamura’s new novel, Audition, a stranger walks into the unnamed narrator’s life, claiming to be her son. An actress stuck in rehearsal-limbo, the protagonist initially dismisses Xavier’s theory. She maintains she had aborted, that the journalist interviewing her on her personal life made an error. But Xavier’s beliefs unavoidably snake in, inextricable from her professional anxieties. Audition unfolds as a deliberately airless monologue, the middle-aged actress steering us through projections favouring her side of the tale.

To saunter into this novel’s tautly clenched psychodrama is to concede to its manipulations, bold provocations. As Kitamura unleashes a vortex of debates around authenticity of account and performance, her heroine’s version increasingly loosens in an amoral web. By turns, Audition slithers like an archetypal stranger-in-the-woods riff and a twisted family undoing.

The novel opens with an expanded set of hypothesis. To a passerby, how would the meeting between the narrator and the twenty-something Xavier look? Kitamura floats various fantasies but she has a wilder trick in store. In this dance between reality and illusion, no singular assertion sustains. Among the actress, her husband and Xavier, their claims keep shredding till we no longer know whom to turn to.

When we meet the narrator, she’s struggling with a particular point in her new play, The Opposite Shore. It’s a moment of metamorphosis where her character takes off. The playwright, Max, insists, “It’s the moment where she locates her emotion, where the play breaks open, when she steps forward into life”. But the narrator is in knots over how to approach it and tackle it. An actress who has had considerable success, she is, however, limited by her racial identity. This project is a promising one and if it lands right, she can revitalise her career.

Kitamura drapes characters in non-specificity. We encounter their outlines shifting shape, gestures filling with new meaning in sudden, stark contexts. These characters cannot be pinned down. They operate in a shadowy realm of intrigue and deception. “There are always two stories taking place at once, the narrative inside the play and the narrative around it,” the narrator muses, “and the boundary is more porous than you might think; that is both the danger and the excitement of the performance.” Kitamura isn’t interested in appearances so much as she is in picking at scabs of exchanges and offerings. An eerie hidden layer vibrates throughout the novel. Behind every sculpted perception lies many truths tucked out of clear view. In a minor strand of the novel, a theatre director unethically coasts on an actor’s undisclosed dementia to shape a performance.

The language is clinically spare. Instead of sinewy details, slivery sketches of characters, and what’s churning them soak the pages in an uncomfortable damp. Is Kitamura being vague just for the sake of it? This glassy language is bound to elicit clashing opinions. What’s the measure of spareness that is effective, not overly designed? Audition walks between the two ends. Max describing the narrator’s character as “arid, cold” seems to subsume the novel itself. The narrator, though, privately confesses not seeing her character in that light. Kitamura wrenches characters together into confined spaces, whilst heightening alienation.

Every relationship in the book hints at frosty calculations within, each interaction shaded with concealment. Xavier swiftly ascends the rungs at the narrator’s theatre production. The narrator’s marriage has reached a stage of convenient disguise. Her affairs are an open secret with her husband, Tomas. Their relationship has sloughed into an acceptance of her straying as essential to its endurance. It’s a settled resignation into the rhythm of domesticity. Yet, possible intimacy with Xavier injects a blood rush. This stranger, young enough to be her son, kindles fresh fault lines.

Xavier flits between sexual charisma and a son’s complicated attitude. In the first section, Kitamura exquisitely draws out the knife’s edge the narrator and Xavier tread. There’s seduction, mystery and an unease in moral boundaries dissolving. It’s further compounded with him being imitative of her mannerisms, or so she thinks. She senses circling a transgression. Should she act on it or withdraw? The novel intercuts this ambiguity with ideas around performance and identity. This is a flirting experiment palpably alert to its possible collapse. Kitamura breaks reality into countless shards, each reflection disfiguring all predating notions. It’s about the intractable selves we inhabit, a single one interlocking into an unpredictable continuum. The novel builds a vestibule where several narratives and iterations of play-acting jostle for primacy. As the narrator seeks to close the gap between the text and her interpretation, she can’t shake off its fallout.

Audition’s structural bifurcation deepens the unfamiliarity ripping among known people. A tilt of the prism throws up fresh angles. The two disparate sections play out like probabilities built around the son. The trio keeps changing its configuration. We expect the narrator-Xavier equation to head in a certain direction, before Kitamura exacts an audacious flip. It’s a leap that could snap a lesser novel, but Kitamura wields a tight, chilly control over the reins. Xavier’s presumption of him being her son actually gets enshrined in the novel’s second half. It becomes the bulwark. Abruptly, he morphs into her son. Expect no logical glue here. The switch is shrouded in naturally persuasive fluidity. However, the narrator remains a distant mother. It’s Tomas who’s more visibly enthused when Xavier proposes staying with them. He welcomes his son but also becomes servile to him. Tomas makes every fleeting wish of Xavier his command. The situation becomes more peculiar when Xavier’s girlfriend, Hana, also moves in. Rifts between the narrator and her husband grow. The discord intensifies.

She’s unnerved by Tomas’ renewed appetite, realising, “And I suppose in the sudden mood of expansiveness, I had the feeling or suspicion or revelation that our life together—it hadn’t been enough.” She cannot fathom why Tomas is bent on servicing every whim of the young couple. Where’s her own maternal zest? She wonders. Why does she feel stingy, withholding while her husband plays the perfect, generous father?

Kitamura fashions an internal landscape with her heroine’s flickering thoughts working the narrative engine. The internal evocation runs in tandem with a stony remove. It’s impossible to tell when partial falsehoods sprout into absolute ones. Even when the family gathers, it feels more constructed than organic. All members enact prescribed social roles, a cleft between their desires apparent. The narrator draws a blank while recalling her own son’s youthful years. The Xavier now holed up in the house radiates pure unusualness. His old habits have vanished, his new self emotionally inaccessible. Hemmed between tenuous selves, we can barely cobble together the narrator’s verifiable reality.

As Xavier intrudes deeper into the narrator’s marriage, the masks come off. It’s all piloted to a spectacularly theatrical climax, a confrontation of naked emotion and physical impulses. The preceding sexual hum amplifies inexorably. “I thought it was true that a performance existed in the space between the work and the audience, that it existed, and was made, in that space of interpretation,” the narrator gets sucked into an abyss of her own making. The climax tears through the artfully muted tone in a dramatic reckoning. Audition knows how to weave an elusive spell as well as when it must soften. This thawing reveals characters in an even icier light.

Debanjan Dhar is a film fest-junkie & is fascinated by South Asian independent cinema

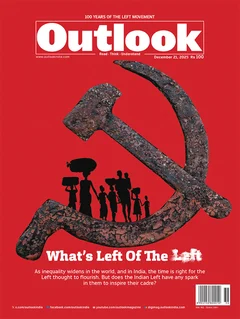

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

This article appeared as Who Am I? in Outlook’s December 21, 2025, issue as 'What's Left of the Left' which explores how the Left finds itself at an interesting and challenging crossroad now the Left needs to adapt. And perhaps it will do so.