Summary of this article

India’s daily hygiene failures are tied to caste-defined labour, not just a lack of “civic sense.”

Dalit sanitation workers carry the burden of national cleanliness while facing social disgust and disregard.

India cannot fix its sanitation problem without confronting the caste psychology that offloads responsibility onto others.

It will be a foolhardy to look for an Indian who has not littered, spat on the street, thrown trash out of running vehicles, dumped waste in riverine areas, piled heaps of garbage in parks or religious centres, painted walls with disturbing precision of pee, shat on railway tracks or open fields, or decorated the walls with tobacco stains.

There is hardly a place in India where you would not be greeted by disturbing piles of waste, sewer lines packed with plastics, and discarded materials blocking the blackened waters of our colonies, or loud music blasted at festivals—from Ganpati, Muharram to Bhim Jayanti. Despite all the noble initiatives of cleaning India (Swachh Bharat Mission) and asking taxpayers to contribute to the coffers for this project, we are still a big, failed nation when it comes to sanitation and hygiene.

Let’s face it. We were once the person who we now detest assiduously. We have done all what we so vehemently protest against now. Schools exhorted on their walls that “cleanliness is godliness”. Yet, at the centre of religious social gatherings, we defeat the gods at their own game.

With the advent of social media, we are forced to face the reality on our screens while wrapped in the cosiness of our clean house. We clean the house at the expense of our surroundings, where we dump the waste that naturally finds its way into our house.

The usual response given to this embarrassment is the absence of civic sense in India. What is civic sense? Does it have any original definition? There isn’t, but the catchphrase has caught the attention of the group of Indians who repel second-hand embarrassment that cannot be avoided any longer.

This phrase is loaded with the history of social culture bereft of caste sensitivity that lies at the heart of our national consciousness and vocational caste definitions in general.

The person responsible for cleaning after our filth is the designated Dalit, who is scorned for being amidst our intimacy, yet is disregarded for the invaluable labour they provide.

We commit social infidelity upon our countrymen by isolating one with the other around responsibilities and accountability. We litter because it is someone else’s responsibility to clean up after us. I used to hear from people that if we clean up ourselves, we would be depriving the person of their job. The same was heard in hostels or public places where we used to live. The maid, mother, and manual scavengers are treated as people who provide us services that are their birth-based responsibility.

When I went overseas, the responsibility of maintaining cleanliness was upon the individual whose property it was. Cleaning our toilets or the common areas was a regular habit and one didn’t see it as going out of the way. It took me some time to realise that the quality of labour and respectability was exponentially higher there.

I wondered where I would see this Gandhian habit of cleaning the toilets in our country? I was informed that Wardha is a place where the Gandhi-inspired Bajaj family, which runs educational institutes, asks freshmen to take up responsibilities, including cleaning the toilet pit. Unfortunately, M. K. Gandhi has failed to liberate people struck in the muck of caste disgust.

The person who looks after cleanliness is the most sacred person because s/he is like our mother who ensures the family is taken care of. Yet, our national caste consciousness robs us of the emotion of empathy.

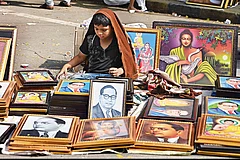

In India, the person responsible for cleaning after our filth is the designated Dalit, who is scorned for being amidst our intimacy, yet is disregarded for the invaluable labour they provide. Dalits are our closest connection to reclaiming our personality. They are a hidden safety valve in our hearts that need to be embraced by each and everyone, so we share the role of keeping our surroundings clean. Cleanliness has to start in the mind first.

If Dalits gave up their job, society would be doomed and India would suffer epidemically. The sweepers of the Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD) had proved this during the strikes in the 1980s. Vijay Prashad has shown in his Untouchable Freedom how the colonial state attempted to usurp the right of the mighty empire over the caste of labour of Dalits.

While this was done, and Dalit labourers of the MCD went on strike, the entire city was at a standstill with a gory depiction of dystopia as a consequence of non-Dalit participation in maintaining the cleanliness of their surroundings.

Civic sense also means being inconsiderate and not respecting society and national laws. Thus, the idea of civics as a condition of citizenship is a prelude to the exercise of an agreeable social contract. Civic sense is catchy, almost trend-like to hide one’s complicity. Once an act is labelled as lacking civic sense, we overcome our responsibility. Social media creators, the media, and some commentators have jumped on this wagon of the absence of civic sense in India. What it means and how it operates is not wholly explored.

For a foreigner’s eye, this is not comprehensible. Many visitors often remark about the lack of responsibility, while Indians respond with a lack of accountability. Two views of looking at the same problem. The foreign person sees this as one’s responsibility to maintain cleanliness. The Indian wants someone else to be held to account, not her/himself.

It is about the guilt-free psychology that caste bestows upon us. We feel compelled to export the accountability to the neighbour, the state, the government, or people’s karma. Rarely do we face the wrong as wrong and work on correcting it.

Therefore, civic sense is a caste issue and it must be viewed within a longer historical context. We cannot invent a flashy explainer for an easily explainable reality that exists amidst us.

(Views expressed are personal)

Suraj Milind Yengde is the author of Caste: A Global Story and a contributor editor at Outlook

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

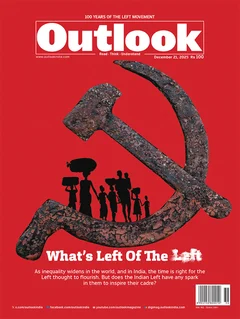

This article appeared as 'The Caste Of Civic Sense' in Outlook’s December 21, 2025, issue as 'What's Left of the Left' which explores the challenging crossroads the Left finds itself at and how they need to adapt. And perhaps it will do so.