Summary of this article

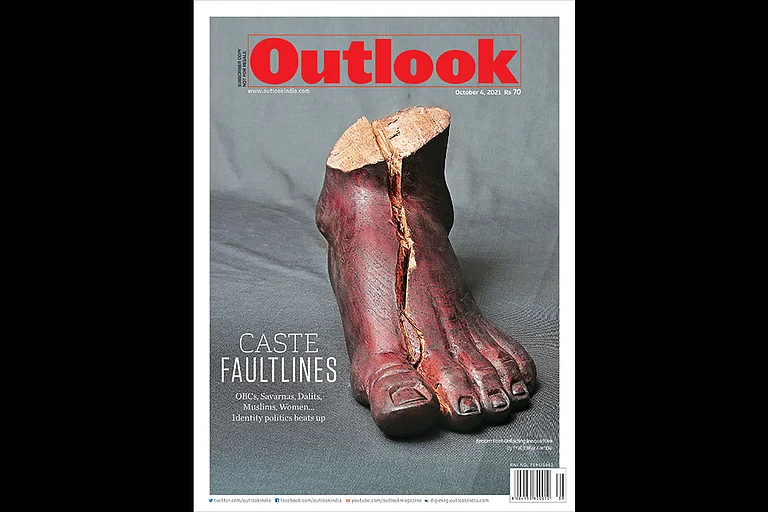

Violence and public humiliation of Dalits persisted, with data showing caste atrocities remain widespread and underreported.

Policy interventions such as the Karnataka Social Boycott Bill and the nationwide caste census were steps toward redress, yet caste continued to structure India’s social and institutional landscape

Caste-based labour, including Devadasi practices and manual scavenging, highlighted enduring social hierarchies despite legal prohibition

Just before the close of the year, another story of lynching entered India’s archive of caste violence.

Ramnarayan Baghel, a 31-year-old Dalit migrant worker from Chhattisgarh, was beaten to death in Kerala’s Palakkad district on December 17. Baghel had come south only weeks earlier in search of work, and was employed at a construction site near Walayar.

Locals accused him of theft. They repeatedly demanded to know whether he was “Bangladeshi.” No stolen items were found. Police later confirmed there was no evidence of any crime.

A video of the assault circulated online. It showed a mob striking Baghel on his head and face and hurling abuse. The post-mortem recorded at least 80 injuries across his body. Dalit organisations and migrant-worker collectives called it what it was.

It was a lynching shaped by caste prejudice and regional hostility.

Violence as Continuum, Not Exception

Baghel’s death was not an aberration. It became a grim reminder of how caste does not merely define India’s past. In 2025, it continues to structure its present. Some of these incidents barely entered national news cycles.

In June, a Dalit wedding was halted mid-celebration when upper-caste villagers objected to the family using a marriage hall. Guests were beaten with sticks as caste slurs filled the air. This incident happened in Rasra, Uttar Pradesh.

In Madhya Pradesh’s Narayanapura village, a Dalit farming family was assaulted while sowing soybean on their legally-owned land. Their seeds were taken away by the attackers. This was an assertion of who controlled land and labour.

Again, in Odisha’s Ganjam district, two Dalit men were accused of cow smuggling. They were publicly humiliated. Their heads were shaved. They were forced to crawl. They were made to drink dirty water. Videos were circulated online.

Women being killed for marrying outside caste lines. Workers beaten for asserting rights. Students dying by suicide after faced harassment in colleges and universities.

Data confirms what these stories suggested. Between January and June 2025, Citizens for Justice and Peace documented 113 caste-based atrocities against Dalits. Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu reported the highest numbers. The National Crime Records Bureau recorded 57,789 cases registered for crime against Scheduled Castes in 2023 nationwide. These numbers are understood to be conservative, since everyday violence, intimidation, and social boycotts often go unreported.

The struggle for dignity continued

It was also in the same year that renewed focus had to be placed on caste-based labour. The labour that society needs but does not dignify.

In Karnataka, activists foregrounded the continued existence of the devadasi system. Young girls from marginalised castes are still dedicated to temples, and later pushed into cycles of exploitation. Estimates of devadasi numbers vary widely. From 48,000 in a 2011 National Commission for Women report to nearly 4.5 lakh in the 2015 Sampark Report. A 2022 National Human Rights Commission estimate placed Karnataka’s count alone above 70,000.

Responding to decades of advocacy, the state approved the Karnataka Devadasi (Prevention, Prohibition, Relief and Rehabilitation) Act, 2025. Drafted with inputs from thousands of devadasi women and activists, the law criminalises dedication ceremonies and promises rehabilitation, even as fresh surveys reveal gaps in implementation.

Caste-based labour discrimination persists beyond temples. Manual scavenging, officially banned since the 1993 Act, continues to claim lives. Around 294 deaths were reported in Parliament between 2020 and 2024, with more than 1,200 deaths recorded since 1993.

Cremation work at Varanasi’s Manikarnika and Harishchandra ghats remains concentrated among Dom families with around 20,000 people tied to inherited occupation.

Merit, Institutions, and the Limits of Equality

Not just labour and violence, caste also shaped access to prestige and power. In June this year, Dr Ashok Kumar, a Dalit physicist at Delhi University and contributor to CERN experiments made news, and this time not for his achievements.

Dr Kumar was denied promotion under the “Not Found Suitable” category. His academic record, an h-index of 120 and a share in the 2025 Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics, made the decision difficult to explain as merit-based. Two junior colleagues were promoted instead.

Activists pointed out that over 60 per cent of reserved professor posts and 30 per cent of associate professor posts at Delhi University remain vacant.

This is often justified through similar assessments. A parliamentary committee report the same year revealed that IIT Delhi had only 20 SC and 8 ST faculty members among 642. This goes far below mandated quotas. Faculty members reported barriers to promotion and resistance to research engaging with caste.

Corporate spaces mirrored these patterns. A complaint by an IndiGo employee in Gurugram alleging caste abuse by senior colleagues led to an FIR and national scrutiny. It seems the promise of meritocracy had not erased inherent and inherited bias.

Law Against Silence: Karnataka Social Boycott Bill

In December, Karnataka passed the Karnataka Social Boycott (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Bill, criminalising caste-based social exclusions like denying individuals access to work, water sources, or religious and social spaces. These punishments are often enforced by informal panchayats. This law targets such practices that often leave no physical injuries but devastate livelihoods. The law allows police to act suo motu and prescribes prison terms of up to three years. Karnataka became the second state after Maharashtra to formally recognise social boycott as a form of violence.

Counting the Uncounted: When Caste Became Policy

This persistence of violence exposed that caste was not merely surviving. It was being enforced through public punishment, social exclusion, and silence. That reality shaped this year’s most consequential policy decision.

On April 30, after sustained pressure from the Opposition and civil society groups, the Cabinet Committee on Political Affairs approved the inclusion of caste enumeration in the national census. It will be the first comprehensive, nationwide enumeration since 1931.

For decades, only Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes were counted, leaving OBC populations statistically invisible. The Mandal Commission’s estimate of OBCs at 52 per cent in 1979 was never backed by census data. The 2011 Socio-Economic Caste Census attempted to fill the gap, but most of its findings remain unpublished. In 2025, counting caste itself became unavoidable.

The upcoming census, described as India’s most technologically advanced, will deploy over 35 lakh field workers. It will use mobile applications and have provisions for online self-enumeration. Supporters argued that without accurate data, welfare policies and reservations rely on guesswork. Critics warned that enumeration would harden identities. It may also deepen political polarisation. But the debate itself marked a shift that caste was no longer something the state could afford not to see.

With Ramnarayan’s lynching, 2025 left behind no illusion of a caste discrimination-free India. Caste shaped who lived, and who died. Who was counted, and who was ignored. Who laboured unseen, and who advanced. The year ended where it began.