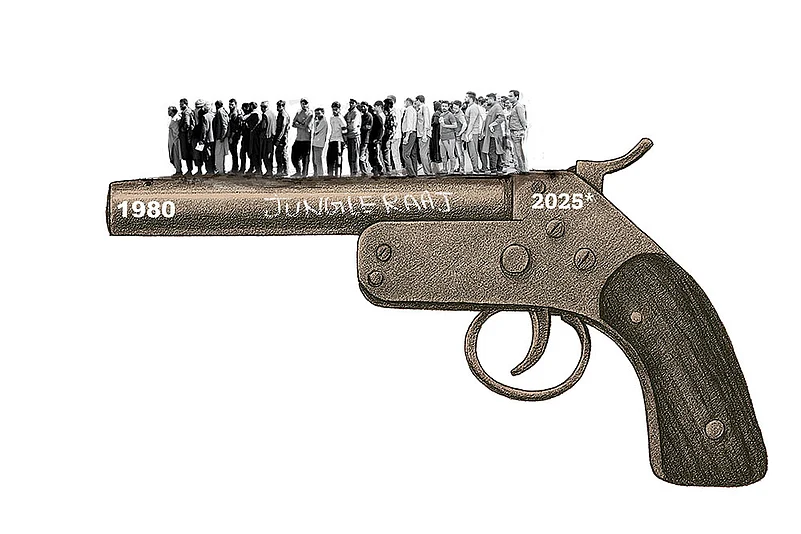

From the murders of Ajit Sarkar and Brij Bihari Prasad to massacres across Magadh and Seemanchal, Bihar’s history shows how Bahubalis, militias and Naxal groups shaped a bloody political landscape.

when Nitish Kumar briefly became chief minister for seven days in 2000, jailed Bahubalis like Surajbhan Singh and Munna Shukla were released to attend the assembly and support his government, showing bipartisan complicity.

The roots of political violence go back to the panchayat elections of the late 1970s, when the measure of each election’s success was not the turnout, but how many killings took place compared to the last one

Murders in Mokama and Purnea ahead of Bihar elections highlight the deep-rooted nexus of caste rivalry, strongmen politics and violent electoral competition.

From the murders of Ajit Sarkar and Brij Bihari Prasad to massacres across Magadh and Seemanchal, Bihar’s history shows how Bahubalis, militias and Naxal groups shaped a bloody political landscape.

Experts trace this culture to the 1970s–90s, when booth capturing, dominant-caste musclemen and party patronage institutionalised criminalised politics, leaving Bihar’s democracy under the shadow of the gun.

The murder of a Jan Suraaj Party campaigner during a rally on October 30 in Mokama, in Bihar’s Patna district, six days ahead of the first phase of assembly polls has brought the spotlight back on the violence that has long dogged electoral politics in the state, where stories of gang rivalries, caste feuds and political vendetta resurface every election season. The police investigation after Dularchand Yadav was run over and killed while campaigning for his party’s candidate revealed that the motive stemmed from a local rivalry with the Janata Dal (United) candidate and influential strongman Anant Singh, who was named along with several others as the accused in the first information report (FIR).

Four days later, just 48 hours before polling, Naveen Kushwaha, the elder brother of a local JD(U) leader, Niranjan, was found dead with his wife and daughter under mysterious circumstances in their home in Purnea in north Bihar’s Seemanchal region. Naveen had run for the Lok Sabha in 2009 on a Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) ticket. Investigating the possibility of accidental death, suicide or triple murder, the police questioned several people, but no murder charge has yet been established.

Politics in these parts has always smelled of gunpowder, and the recent incidents have only reopened old wounds as a reminder that violence remains the accepted grammar of politics. The blood shed here continues a political tradition in which caste equations, rival ideologies and electoral interests converge to legitimise violence, giving the region its lasting reputation for a “gun culture”. What were once decided in the caste-based panchayats of the past are now fought as battles for political dominance, also on social media.

Between 1980 and 2000, Purnea became synonymous with brutal political killings. On June 14, 1998, the Communist Party of India (CPI) legislator Ajit Sarkar, who was widely respected for standing with poor and landless peasants, was gunned down in broad daylight with his driver and bodyguard while returning from a public meeting. They were ambushed by AK-47-wielding assassins who came on motorcycles. The murder sent shockwaves across Bihar. The FIR named strongmen Rajesh Ranjan alias Pappu Yadav, Rajan Tiwari and Avdhesh Mandal, among others. The case was handed to the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), which filed its chargesheet in 1999. In 2008, a CBI court in Delhi sentenced Pappu Yadav to life imprisonment, but the Delhi High Court acquitted him in 2013 for lack of evidence.

Just two days after the CPI MLA’s assassination, another high-profile murder shook the state. On June 16, 1998, motorcycle-borne gunmen killed Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) minister Brij Bihari Prasad, a close aide of Lalu Prasad Yadav, while he was being treated at a Patna hospital under police protection. The assassination was allegedly orchestrated by Munna Shukla and Rajan Tiwari, both powerful legislators locked in a long-standing turf war with Prasad. The killing symbolised the fusion of politics, crime and power that defined Bihar in the 1990s, when brute force became the ultimate currency of influence.

As the politics of social justice intertwined with criminal networks, many strongmen built parallel power structures in their regions. In Mokama, Anant Singh became the unchallenged “Chhote Sarkar”. In the Magadh region (Nawada, Jehanabad, Gaya), Ashok Mahto, from the Kurmi caste, gained notoriety for brutal massacres and clashes with the dominant-caste Ranvir Sena. Anand Mohan Singh, a Rajput leader from the Kosi region (Saharsa, Madhepura, Supaul), rose through the Samata Party ranks and became a Member of Parliament before being convicted for the 1994 murder of Gopalganj district magistrate M.G. Krishnaiah.

In Siwan, Mohammad Shahabuddin built a formidable Muslim power base under the RJD’s patronage, and his reign later inspired films and books. In the Seemanchal region, Taslimuddin emerged as another strongman and a prominent minority leader. Meanwhile, in Muzaffarpur and Vaishali, the caste rivalry between Munna Shukla and Brij Bihari Prasad deepened the violent polarisation between the Bhumihars and the backward castes.

Cinematic portrayals of Bihar’s Bahubalis (strongmen) further cemented the image of a state trapped in crime and fear. Many critics dubbed the 1990s under Lalu as “Jungle Raj”, a term his opponents still invoke to describe that period.

“The surge in political killings after 1990 is undeniable, but blaming Lalu’s regime alone is historically inaccurate,” says Supriy Ranjan, a PhD scholar at Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University researching the nexus of crime and politics in Bihar. Ranjan points out that when Nitish Kumar briefly became chief minister for seven days in 2000, jailed Bahubalis like Surajbhan Singh and Munna Shukla were released to attend the assembly and support his government, showing bipartisan complicity.

Ranjan argues that the politicisation of crime began in the 1980s under the Congress. In 1980, five Bahubalis were elected as MLAs, most with Congress tickets. The then CM Jagannath Mishra, he notes, was infamously called “the tormentor of Bihar” for presiding over the breakdown of state machinery and the rise of violence. In his research, Ranjan finds that about 60 per cent of Bihar’s Bahubali politicians hail from the dominant castes—Bhumihars, Rajputs and Brahmins—followed by 22-25 per cent Yadavs and five per cent Muslims. Among Dalits, only Suresh Pasi is seen as having any comparable influence.

In short, Bihar’s strongman culture has historically been dominated by the dominant-caste elites. Backward-caste leaders began entering this space in the 1980s, and expanded rapidly in the 1990s as their political assertion grew through universal suffrage and economic shifts.

Meanwhile, between 1976 and 2001, around 100 caste-based massacres claimed 850 lives, according to one study. The bloodshed particularly scarred the central districts like Gaya, Bhojpur, Jehanabad, Aurangabad and Arwal. At Belchi in 1977, Dalits and backward-caste villagers were killed. At Dalaelchak-Bhagora in 1987, the Maoist Communist Centre [MCC, which merged with the CPI(ML) (People’s War) in 2004 to form the outlawed CPI (Maoist)] massacred over 50 dominant-caste villagers. At Bara in 1992, the MCC killed 35 Bhumihars. At Bathani Tola in 1996, the dominant-caste Ranvir Sena slaughtered 21 Dalit labourers, including women and children. At Laxmanpur-Bathe in 1997, this private army of landlords killed over 50 Dalits. At Rampur Chauram in 1998, the MCC killed nine Bhumihars. At Shankar Bigha in 1999, the Ranvir Sena killed 23 Dalits. At Senari in 1999, the MCC massacred 34 Bhumihars. At Miyanpur in 2000, the Ranvir Sena slaughtered 35 Dalits and backward-caste peasants. These massacres were part of a cycle of caste retribution, where dominant-caste landlord militias and Naxalite parties waged a bloody war of vengeance.

Veteran journalist Manikant Thakur, who has reported on Bihar’s politics since the 1970s, observes that the massacres peaked in the Magadh region after the 1990s. “Bihar was synonymous with mass killings,” he recalls. “During the ballot-paper era, booth capturing was rampant, blurring the line between politics and organised crime. The roots of political violence go back to the panchayat elections of the late 1970s, when the measure of each election’s success was not the turnout, but how many killings took place compared to the last one.” Bihar, among all the states, needed the largest deployment of paramilitary forces during polls and soon the violence spilled into everyday life.

Citing a documented case in Begusarai, where supporters of the then CM Sri Krishna Singh brutally assaulted his CPI opponent in 1952, nearly killing him, Ranjan’s research traces the violence back to India’s first general election. By 1957, the first recorded instance of booth capturing took place in Begusarai’s Rachiyahi village, allegedly orchestrated by Kamdev Singh, known as the “Godfather of Booth Capturing”. “Today’s Bahubalis were once known as ‘booth managers’,” says Ranjan. “They were local musclemen, often dominant-caste landlords, hired by political parties, mostly the Congress, to secure votes by force. These men eventually began contesting elections themselves.” Thakur says they realised the leaders depended on them for victory. “The parties reluctantly gave them tickets, thereby institutionalising the criminalisation of politics.” Every election since has revived the question: can democracy in Bihar ever escape the shadow of the gun?

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Md Asghar Khan is senior correspondent from Jharkhand.

This story appeared in print as 'Crime, Caste and Politics' in Outlook’s November 21 issue Solitude Of Power, in which we trace Bihar’s enduring political grammar, where caste equations remain constant, alliances shift like sand, and one man’s survival instinct continues to shape the state’s destiny.