The former gangster and Jan Suraaj worker Dularchand Yadav was killed on October 30.

The murder has put the Mokama district on high alert.

Arrests have been made, and Mokama MLA Anant Singh, contesting on a Janata Dal (United) ticket, is in judicial custody, but justice is an elusive concept in Bihar.

Outside a blue building in Barh, a few police personnel are looking out for any signs of trouble. The area has been on alert since the killing of a former gangster, Dularchand Yadav, in Mokama’s Tartar village on October 30. The feast is due. It will happen after justice is delivered. But justice is an elusive concept in Bihar, where criminalisation of politics has existed since time immemorial.

Arrests have been made, and Mokama MLA Anant Singh, contesting on a Janata Dal (United) ticket, is in judicial custody for the murder of a former Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) leader who had allegedly called Singh’s wife and ex-MLA Neelam Devi a nautch girl before being killed after backing Jan Suraaj’s Piyush Priyadarshi.

Since then, the area has been on high alert. Violence during elections is not new in Bihar. In 2005, JD(U)’s Nitish Kumar had fought the elections on the promise of ending Jungle Raj in Bihar. It is ironic, then, that the 2025 Bihar assembly election is again being fought by the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) alliance with that narrative. While the Mahagatbandhan is faced with the task of fighting that label that has become synonymous with RJD founder Lalu Prasad Yadav’s reign, where the rule of law had been suspended and killings and kidnappings were reported frequently, the truth is not always that black and white in Bihar, which has witnessed massacres and caste-wars and seen criminal-politicians defy law and order and become ministers.

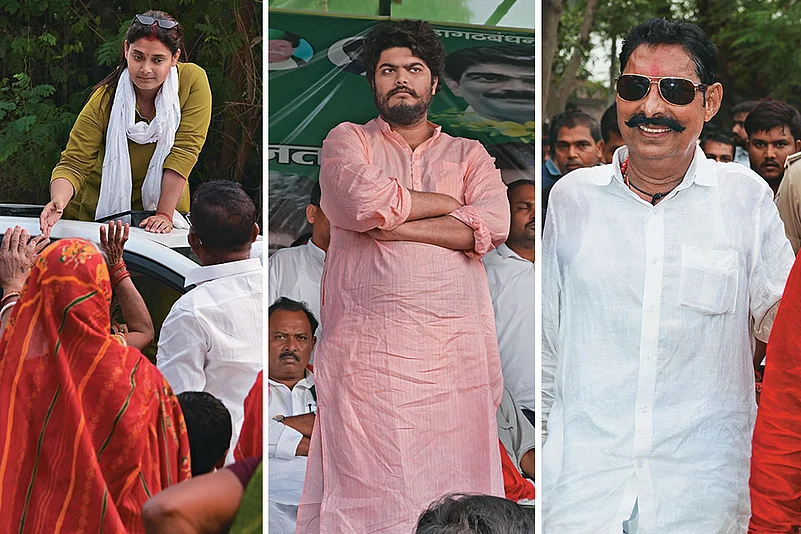

A look at the candidates from both the alliances confirms that many Bahubalis (strongmen) are in the electoral fray and in cases where the Bahubalis have been convicted, their spouses or children are trying to claim what they think is theirs. Over 22 such candidates or their kin are contesting this time: nine from RJD, seven from JD(U), four from BJP, two from Lok Janshakti Party (LJP) and one from Jan Suraaj. In 2020, there were 17. Nearly half now face criminal cases.

On November 9, the Director General of Police, Vinay Kumar, said in a press conference that the police are the biggest Bahubali and all such contestants are under surveillance.

In this timeless part of the world where water can submerge habitations, the men who sit through the day watching the road that leads into the village of Tartar in Mokama in Bihar, say that not much has changed for them. Through the decades of promises and chaos, they have known that to find dignity, they have to be born again in another caste. Mokama, the unstable land where mobs fight for supremacy and where men like Anant Singh, the JD(U) incumbent MLA who is commonly known as Chhote Sarkar here and is a strongman who has the patronage of the chief minister Nitish Kumar of the JD(U), become legends.

The law and order failure in Bihar is not a new story. The audacity of the criminal-politicians is known to many, including police officers and administration personnel.

On the edge of the horizon, a road, an elevated one, snaked through, splitting Mokama into two parts. One is prosperous with the Ganges gently flowing by; the other is the wetlands, where the poor deal with floods as a way of life. In this existential wasteland with a legacy of violence and prejudice and fear, the rise of Anant Singh, who is a Bahubali with more than 28 cases against him, is not an accidental one but a planned necessity for political leadership in Bihar.

Wooed by both JD(U) and RJD, he remains in the spotlight with any convictions against him set aside by the courts, like in 2024 when he walked out of prison after a rigorous sentence of ten years for possession of weapons was set aside by the Patna High Court. His wife, who had won from Mokama on an RJD ticket, switched over to the JD(U) during the floor test in 2022.

“It is the opposition’s conspiracy,” Anant Singh told Outlook before he got arrested. “The public is the Bahubali. I am just their servant.”

Unlike Lalu Prasad Yadav, who was at first averse to upper castes and tried to dismantle their influence in politics and many say that he was a political necessity in Bihar back then, Nitish was more accommodative in his social engineering.

Both leaders have extended political patronage to Bahubalis to win several seats.

Mokama’s tryst with Bahubalis is not new. In this election, the RJD has given the ticket to Veena Devi, the wife of another Bhumihar strongman, Suraj Bhan Singh, who is barred from contesting elections after his conviction. In September 2025, the MP-MLA court in Begusarai convicted the former MP in a 33-year-old case involving an attack on a police team. While Singh was sentenced to one year in prison, he got bail.

On October 9, 1992, gunmen attacked police at a Barauni wax factory, leading to Suraj Bhan Singh’s arrest.

Before Anant Singh came into the picture, it is said that Suraj Bhan Singh had helped Nitish Kumar win the Barh Lok Sabha seat in 1999. In 2000, he himself contested the 2000 Assembly elections from Mokama, against his former boss Dilip Singh and won.

In 2004, Suraj Bhan Singh joined Ram Vilas Paswan’s LJP and won from Ballia, but four years later was convicted for murdering farmer Rami Singh and barred from polls. Released on bail in 2012, he backed his wife, Veena Devi, who won Munger in 2014 and now faces Anant Singh in Mokama. When she attended Dularchand Yadav’s funeral, stones were hurled; another reminder of Bihar’s crime-politics nexus. Dularchand, a rare non-Bhumihar to rise in Mokama, had been named with Dilip Singh and Nitish Kumar in the 1991 murder of Congress worker Sitaram Singh, a case quashed by Patna High Court in 2019.

Caste lines run deep here. At Dularchand Yadav’s funeral, Bhumihars say Yadavs hurled abuses, yet both alliance candidates remain from the upper caste.

Outside a polling booth in Mokama town, upper caste villagers sat at a little distance from the polling booth. An IAS officer once said this was meant to deter lower castes from voting. In 2005, the officer had ordered everyone indoors. But defiance has returned now. With Anant Singh in custody, loyalists still back him for the protection he promised.

During the 1995 Bihar Assembly election, 243 candidates faced charges, writes journalist Vikas Jha in Bihar: Criminalization of Politics (1996). That’s when JD(U)’s Lalan Singh brought Anant Singh to Nitish Kumar.

“He asked Anant Singh if he could ask him for a promise. Anant Singh said he could and that is how he aligned himself with Nitish Kumar,” said Gyan Prakash Singh from Nadwan village in Barh, where Anant Singh hails from.

When Nitish Kumar first became the chief minister in 2005, Anant Singh, who is an upper-caste Bhumihar, had weighed him in silver. Gyan Prakash Singh even remembers it was 67 kilograms.

And that’s how his reign began in Mokama. With gang wars, gun fights and a lot of charity. That there is a delusional aspect to his story is evident in the way he conducts himself. A person is at hand to tie his shoelaces, another to hold the ashtray when he smokes. The loyalty he commands could be a case of myth-making. They tell stories of how he swam across the river to kill the man who killed his eldest brother, Birachi, who was a mukhia (village headman) and a landlord like his father.

That made him the undisputed strongman in these parts and there were videos circulating on YouTube of him dancing while brandishing an AK-47.

Known for his defiance and quirks—he is said to have kept a python at home—Anant Singh once declared he was done with JD(U). By 2013, over 83,000 criminals had been convicted in Bihar, and the rule of law seemed to return briefly. Yet patronage endured: jailed strongmen like Munna Shukla saw their families thrive in politics. Two years into Nitish Kumar’s tenure, Singh allegedly assaulted journalists questioning him about the rape and murder of Reshma Khatoon, though police later claimed the body found near his house wasn’t hers. Now, Munna’s daughter Shivani is contesting from Lalganj on an RJD ticket.

Bandana Preyasi, a senior IAS officer who was posted in Barh in 2005, said that the rule of law is not about convictions but everyday administration.

“Administration can be the biggest Bahubali,” she said.

She was in charge of elections in Siwan in 2009. Back then, Siwan was still considered a dangerous place. Mohammad Shahabuddin ruled the region from the prison.

“It was a bitter election,” she said.

The ducks moved around the compound flapping their wings, unbothered by the presence of strangers who had gathered to get an audience with the son of the notorious criminal-politician Mohammad Shahabuddin of Siwan. The son would carry the legacy of his father. They didn’t answer what this legacy would be. Questions don’t matter here. And answers aren’t given.

The ducks are a continuation of Shahabuddin’s lifestyle. A few men pointed to the palatial structure next door with high walls and iron gates lined with palm trees and said there is a floor entirely dedicated to around 50 Persian cats there. A young supporter had shot a video of the inside of the mansion. Chandeliers, ornate winding staircases and very garish interiors. Shahabuddin had built this house around 2004 in Siwan.

Osama Shahab, the “babu”, is a 31-year-old man who doesn’t talk.

A team of PR professionals who have been camping here for days seemed to be very taken in by Shahabuddin’s story and his conquests. It is, of course, a selective choice, given the fact that Shahabuddin’s trial happened in Siwan and the privileges available to him inside the jail, like a television, were taken away in the end. He died a lonely death at the age of 53 in Tihar jail in Delhi in 2021 during the pandemic. His wife, Hena Shahab, contested twice and lost. Last year, she approached the RJD to make a case for her son’s entry into politics. In such places, a son is the heir. The wife is only the bearer of the comfort and casualty.

In 2021, a man in Siwan told me the weather forecast for the next few days in Pratappur was “broken clouds”.

That was when the news of the death of Shahabuddin reached his village.

The Bahubalis are known to be wooed by all parties. It is not the party, but it is their Robin Hood persona that gives them the power and the agency.

He was angry. He said the administration here feared that if his body were brought down to Siwan, there would be an outrage. In Delhi’s Jadid Qabristan Ahle Islam at ITO, there is a nondescript grave with an epitaph with his name, the date of birth, the date of his demise and where he came from. His son, Osama Shahab, had wanted to take the body of his deceased father to their hometown in Bihar, but the protocol related to the Covid-19 virus prohibited that.

He had been away from Siwan for a long time. The mourning in Siwan lasted for days. From then, the people here said they would wait for the son to take over.

The family had then alleged that the Director General of Tihar Jail (Delhi) had ‘murdered’ Shahabuddin, and his supporters accused the RJD of not doing enough for Saheb.

Shahabuddin was a creature born out of an unholy alliance between crime and politics in a place like Bihar that’s always searching for Robin Hoods to deliver justice, especially in a time when Muslims as a minority feel threatened.

Shahabuddin emerged on the scene in the 1990s when L. K. Advani’s Hindu nationalism movement was at its peak. The 1980s and the 1990s were the decades when Advani led the Hindu nationalism movement and riots happened across the country, including in Bhagalpur in Bihar in October 1989, where organised mobs burnt over 250 villages down, and mass killings took place across the district. Official figures put the death toll at around 1,000 (90 percent of whom were Muslims) but many believe it was much higher. In October 1990, Advani was arrested by Lalu Prasad Yadav in Samastipur in Bihar.

That was the year that Shahabuddin won the elections from Pratappur as an independent candidate from the Ziradei seat. His election symbol was a lion and he was only 23. He defeated Tribhuvan Singh of the Indian National Congress while he was lodged in prison.

After he won the Ziradei seat, Shahabuddin got bail.

Since 1990, Shahabuddin had been elected twice as MLA and four times as MP.

It was the M-Y (Muslim-Yadav) formula that kept the RJD in power till 2005.

Professor Jeffrey Witsoe, who spent years in Bihar researching critical rethinking of democracy and the postcolonial state through an examination of lower-caste politics in Bihar and the author of the book Democracy Against Development (University of Chicago Press), said Shahabuddin was a compromise that Lalu had to make to consolidate his position.

Shahabuddin’s reign was so terrifying that the BJP never dared to open its offices in Siwan back then, Nand Kishore Prasad, the Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) Liberation’s (CPI-ML) politburo member, told me in 2021. He was tasked with overlooking the party’s work in Siwan in the 1990s.

It was in 1997 that CPI-ML’s leaders Chandrashekhar and Shyam Narayan Yadav were killed while they were holding nukkad sabhas in Siwan by Shahabuddin’s henchmen.

Muslims constitute about 20 percent of the district’s population, closely seconded by Yadavs.

In 2016, Shahabuddin had walked out of jail. It was the year Lalu Prasad Yadav returned to power in Bihar in partnership with Nitish Kumar.

Former DGP of Bihar Abhayanand remembers his convoy of over 200 vehicles took more than 14 hours from Bhagalpur Jail, where he was lodged, to get to Siwan because people flocked around the convoy to greet him.

His bail was cancelled by the Supreme Court and on February 15, 2017. He was then shifted from the Siwan jail to a high-security cell in the Tihar jail. He had become an administrative nightmare by then, according to sources in the government.

Shamshuddin, who used to work at the sugar mill in Siwan back then, said Shahabuddin brought peace to Siwan.

“He was a messiah for the poor,” he said. “We will make his son win. We owe Saheb this much.”

So, Osama is now in the race. There is an opaqueness about him. At a rally in Hussainganj in Raghunathpur, where he is contesting from, he stood behind Samajwadi Party’s Akhilesh Yadav as he addressed the crowd. Osama didn’t say a word. He didn’t greet the crowd either.

Akhilesh Yadav, the former chief minister of Uttar Pradesh, has been campaigning for the Mahagatbandhan in Bihar and referred to Osama as a young man who deserves a chance in his bid to woo the young voters in Bihar.

Elsewhere in the region, men recall how Shahabuddin brought development to the region.

“Back then, the doctors couldn’t charge more than Rs. 100,” says Avdhesh Gupta, a businessman from Raghunathpur. “He ended crime here. He built roads. He was our Saheb. We used to feel weakened after he died, but now Osama is here.”

That’s how most stories are told and retold. Nostalgia’s rose-tinted glasses have made many here become very selective about the past. The retelling omits the ugly.

The son will become his father, another man said.

“In due time,” he said.

The flags start to mark the landscape as you enter Siwan. Green and saffron. That’s how habitations are marked here. With defiance and allegiance.

‘Shahabuddin’s reign was so terrifying that the BJP never dared to open its offices in Siwan back then’

In Pratappur, the native village of Shahabuddin, the old house lies in ruins. Across the lane, a white house, which is imposing in its make, stands. The grounds are sprawling. In the open garage, an old jeep is parked.

“He (Osama) will learn to speak,” says Prabhudas Yadav, an elderly man in the constituency.

“His father never spoke much and never asked for votes. He didn’t have to.”

Times have changed since Shahabuddin ruled Siwan, and for his son, it is no easy task to match that reputation, although his public relations team, led by delusion and some misplaced romanticism with the Robin Hood legend of Shahabuddin, makes a case for this silence.

“It is about maintaining power. In the old days of the Delhi Sultanate, the princes talked less and let mystery be their power game,” a man who oversees his PR team said.

Siwan and Raghunathpur are no longer fiefdoms, and Osama is no Shahabuddin. Not yet. With two pending Arms Act cases and no conviction, he stood behind Yadav, who urged voters to back youth like Osama but avoided mention of dynastic politics. Apart from his RJD ticket, little was said of Osama’s past or merit. His affidavit lists only matriculation, an income above eight crore, and “social worker” as his profession, yet locals speak of his “London degree” and his polished demeanour of an educated man who is wary his words might be misread by the media.

Osama enters the political arena at a time when a lot has changed, and the old kind of politics no longer works.

People still queue up at the palatial house the family owns in Siwan, which was built by Shahabuddin around the time he went to jail for the first time in 2004.

Siwan is not an easy place, and Osama was just 10 when his father went to jail.

A Yadav man pointed out a stray and said if Nitish Kumar gives a ticket to a dog, the dog will win, too.

“That’s just to tell you how things are. We are looking at Patna and Delhi. We want Narendra Modi to go, so we will vote for whoever RJD will choose,” he said.

They call him babu and make excuses for him, saying he is too young to understand politics, and this is a heavy load of inheritance.

Osama’s cavalcade whizzed past, and somewhere in the sky, Akhilesh Yadav was returning to his home in his helicopter on November 3.

***

In a landscape where ideologies shift, there is nothing that’s fixed. The Bahubalis are known to be wooed by all parties. It is not the party, but it is their Robin Hood persona that gives them the power and the agency. The party’s role is limited to handing out a ticket.

The law and order failure in Bihar is not a new story. The audacity of the criminal-politicians is known to many, including police officers and administration personnel.

The Jungle Raj fear that the BJP is creating in Bihar shows a lack of narrative for the party in a state where they have not been able to install their candidate as the chief minister in the last two decades. The party’s supreme leaders and their star campaigners, like UP’s chief minister Yogi Adityanath, have been campaigning in the state and Prime Minister Modi himself has had 12 rallies so far.

Their playbook is the same. Infiltrators, Hindutva, etc.

In Raghunathpur, the JD(U)’s Vikash Singh’s campaign song is an ode to loyalty to Ram.

But who is listening? The vehicle tumbled along the bumpy roads and the song faded.

***

As you enter Lalganj in Vaishali district, you hear the pleas on loudspeakers to vote for the daughter who will bring back the glory to the area. Shivani Shukla, 28, got the RJD ticket an hour before the nominations for the Bihar Assembly Elections closed. She calls herself an accidental politician and speaks freely about her father, the Bahubali Munna Shukla, who once held the seat here and is now lodged in Bhagalpur Jail.

But his sway over the place remains. Like Mohammad Shahabuddin’s in Siwan.

Shivani Shukla said she wasn’t going to deny the Bahubali tag.

Her definition is different.

“It is the power that got me the ticket,” she said.

Chinki Sinha is editor, Outlook Magazine.

This story appeared in print as 'Where Angels Fear To Tread' in Outlook’s November 21 issue Solitude Of Power, in which we trace Bihar’s enduring political grammar, where caste equations remain constant, alliances shift like sand, and one man’s survival instinct continues to shape the state’s destiny.