In the realm of politics and violence it is commonly assumed that where politics ends is where violence begins. That politics and violence are opposites, because violence is sheerly instrumental and politics in a democracy is, so to say, tasked to deal, dialogically, to keep violence at bay.

Hannah Arendt’s essay On Violence makes explicit that the violence is practiced through instruments—atom bombs, guns, machines and so on—and is directed against the ‘others’, not as subjects, but as objects, who can be manipulated by its use or threat.

The very idea of violence, for her, goes against the very grain of communicative and interactive politics, against the participatory role of citizens in common life, and against the formation of public good. Good democracies, therefore, experience less political violence than autocracies or bad democracies.

Political violence in Bihar has been instrumental in nature, particularly during the run-up to elections, and in the electoral campaigns for political mobilisations. Where politics and violence are seen, not as opposites, but as part of the continuing political processes.

In the land of Buddha, we have witnessed perhaps one of the worst caste and communal violence, both in terms of scale and intensity. And, of course, there is this regular supply of everyday forms of violence rooted in patriarchy, poverty and pelf. What seems to be in short supply is justice, social-justice. Why is it that violence has been a routine way of practising politics in Bihar? Why is it that Bihar is replete with the stories of violence, tyranny amidst hope?

The Surrealistic Tales of Violence

During the colonial period, the decades of the 1930s and 1940s, Bihar was rife with the popular peasant protests (as Kisan Sabhas), led by the impressive leader Swami Sahajanand Saraswati, against the powerful zamindars (landlords), mainly to address the agrarian grievances. The peasants, majorly the lower castes, wanted two things, their land back from upper-caste zamindars which they had lost due to non-payment of rent and the abolition of the zamindari system. The Mokama region of Bihar was the centre of the movement which still reverberates with the stories of violence perpetrated by the colonial-state and the landlords on the Kisan Sabha’s peasants.

Interestingly, the tales also remind us as to how both the power elites in the Congress and big zamindars appropriated the movements and prevented any major land distribution to landless labourers and sharecroppers. The dominant upper castes, majorly Bhumihars, swayed their control over the political and economic resources, particularly land, and maintained their superiority through violent assertions, up till the announcement of land reforms, post-independence.

One other case of violence, popularly known as the Janeu (sacred thread) movement, erupted during the colonial period (1920s). This was demonstratively an assertion by the backward castes—mainly Yadavs, Koeris and Kurmis—to upgrade and equalise their position to that of the Brahmins in the caste hierarchy simply by wearing a janeu. This enraged the upper castes, particularly the Brahmins, and led to violent backlash against the backward castes.

Both the cases have an uncanny resemblance in the usage of violence as an instrument, in Arendtian sense, to control the political, economic and social power embedded in the State, caste and class.

There is a regular supply of everyday forms of violence rooted in patriarchy, poverty and pelf.

In post-independent India, Bihar is imbued with three kinds of violence, though not mutually exclusive: Naxal violence; caste violence and Bahubali (big goon/gangster) violence. These types of violence are political in nature, in a sense that we see the complicity of the State and its institutions neck-deep into the social dynamics of caste and class. Bihar being essentially an agrarian society (80 per cent rural), the questions of land and land reforms are central to all kinds of political violence. Despite Bihar enacting the Bihar Abolition of Zamindari Act (1950), the first state to do so, and a few more Land Reforms Acts, and despite its Bhoodan Andolan (land donation movement, late 1950s), it could not resolve the basics of agrarian crisis related to land, wages and oppression of landless castes.

The introduction of the so- called ‘Green Revolution’ in Bihar (1960s-1970s), further exacerbated the existing gaps, tensions, and conflicts between the big landlords and the smaller tenant farmers, sharecroppers and landless labourers. Such a condition of hopelessness led to a ‘radical politics of dissent’ by the Naxalites. The Naxal uprising, quite distinct from the earlier agrarian struggles, consisting mainly landless labours and poor sharecroppers, targeted its violence against the Kulaks—rich landlords from the Bhumihar, Rajput, Yadav and Kurmi castes. Their aim was to violently dissolve the vestiges of feudalism and capture political power. The Naxalite movement, however, produced an equally violent backlash from both the upper-caste landlords and their armies.

‘Operation Thunder’ (1976) by the state police, and killings by the upper-caste armies—for instance, Bhoomi Sena, Kuer Sena, Brahmarsi Sena, Savarna Liberation Front, Sunlight Sena and Ranvir Sena—were the counter-violence against Naxalites, which explains what I call Bihar’s ‘circularity of caste-class violence’. For the brutal violence by the Ranvir Sena, Ashwini Kumar, in his doctoral dissertation Peasant Unrest, Community Warriors, and State Power in India: The Case of Private Caste Senas (Armies) in Bihar, notes what the ex-commander of the Ranvir Sena had said, “Yes, we kill the women because they give birth to Naxalites; when the children grow up they become Naxalites and kill us. They (the lower-caste people) give shelter to the Naxalites. We are farmers but we have decided that if they kill two of us, we will ruin their whole khandan (clan); we will kill all of them”.

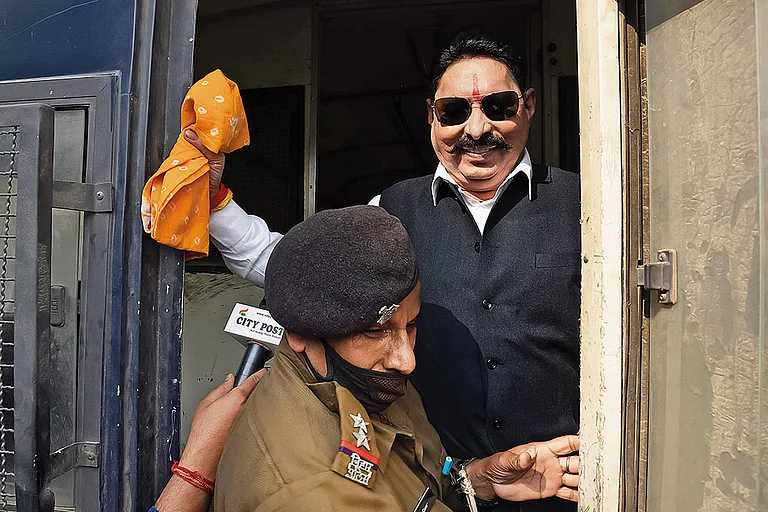

In the 1990s, Lalu Prasad Yadav, supposedly the protégé of Karpoori Thakur, tried to reinvent a new Bihar by giving voice and dignity to backward castes and claimed to ‘annihilate’ the traditionally Sanskritised feudal power structures and caste hierarchies. The two events, the halting of Advani’s Rathyatra and his arrest, and the quelling of the anti-Mandal agitation in central Bihar, led to the sharpening of the deep divisions, both physically and psychologically, between the backward castes and the upper castes. It also led to Lalu’s famous Muslim-Yadav (MY) politics predicated on the non-Brahminical, vernacular and popular-political messaging. During Lalu’s tenure (including that of his wife, Rabri Devi’s, tenure), law and order deteriorated and the fragmentation of upper backward caste accelerated, that propped up Nitish Kumar as his competitor. When Rabri Devi became CM for the third time (2000), we saw ‘Yadavisation of state power’ in Bihar—commonly referred to as ‘Jungle Raj’ by Lalu’s opponents. This period was also marked with the Bahubalis’ rule. These Bahubalis were openly supported by one political party or the other. The gangsters used to get replaced by the changing state power dynamics, for instance upper-caste gangsters—Chhotan Shukla, Bhutkun Shukla, Devendra Shukla, Devendra Dubey and Samrat Choudhary—were being replaced with the new backward caste gangsters—Pappu Yadav, Surendra Yadav, Dularchand Yadav–during Lalu’s regime, who were then countered by the mafia-politicians such as Suraj Bhan, Ranjan Tiwari, Anand Mohan Singh, Aditya Singh and Sunil Pandey with their private caste armies.

The internecine caste war combined with mafia politicians and their big goons gives a curious amalgam, a broad landscape, of political violence, privatisation of state power and near complete absence of governance in Bihar.

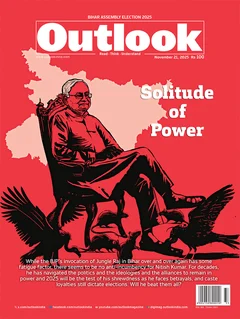

The 2025 elections in Bihar reverberates with three things: one, the long history of unbridled power conflicts imbued with political violence; two, the inherent contradictions between the emergent social order laced with Hindutva politics with the continuing culture of everyday violence against Dalits, Muslims and the poor; and three, the possibilities of the impossibilities. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has urged the voters in his campaigns to keep away ‘Jungle Raj’, reminding them of the rule of the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) and the Congress. He tends to forget that ‘Jungle Raj’ is one small period in the history of political violence in Bihar since colonial times. The real question is how to dismantle this ‘circularity of caste-class violence’ and rescue Bihar from the socio-economic and political morass.

(Views expressed are personal)

Tanvir Aeijaz teaches Politics & Public Policy at University of Delhi and is Hon. Vice-Chairman & Member-Secretary at the Centre for Multilevel Federalism (CMF), Institute of Social Sciences, New Delhi

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

This story appeared in print as 'Bullets Over Bihar' in Outlook’s November 21 issue Solitude Of Power, in which we trace Bihar’s enduring political grammar, where caste equations remain constant, alliances shift like sand, and one man’s survival instinct continues to shape the state’s destiny.