In the 2025 Bihar assembly polls, the BJP-led NDA is banking on the “Jungle Raj” narrative against the Lalu-Rabri era while lacking a clear CM face, as Nitish Kumar’s health and reported dementia raise public concern.

The saffronisation of the socio-political and administrative spaces and the rising anti-Muslim hatred are electoral advantages for the NDA.

The muted response from Prashant Kishor’s Jan Suraaj Party to the murder of its Yadav supporter highlights deep-rooted caste biases and the prevailing anti-Yadav sentiment among Bhumihars.

In the 2025 Bihar assembly election, the incumbent National Democratic Alliance (NDA) is seeking re-election by building a narrative of “Jungle Raj” around the Lalu Yadav-Rabri era (1990-2005). This time, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led NDA hasn’t been able to project its own chief ministerial face. Their incumbent chief minister, Nitish Kumar of the Janata Dal-United (JD-U), is evidently not keeping well, in terms of health. It is largely believed that Nitish is suffering from dementia. For the first time, Nitish has been reciting brief written texts during public meetings.

Conversations and discussions with the electorate from across castes and classes and across the sub-regional and (dialect-based) variations in the poll-bound provinces clearly suggest that the upper castes, more importantly the Rajputs and Bhumihar-Brahmins (Babhans), are more desperate to bring back a regime led, dominated and hegemonised by the BJP with an upper caste chief minister. However, they don’t feel it electorally prudent and wise to be explicit about replacing Nitish Kumar, still a formidable vote-catcher, prior to the polls. Overall, it seems that the NDA will get its votes and support from across castes and communities. Of course, it is also quite visible that the Yadav and Muslim (M-Y) votes would go to the NDA, but in a very small measure. Significantly, Nitish Kumar is cultivating a support base among the women and his cash transfer scheme of Rs 10,000 to women seems to be working in his favour. Overall, the saffronisation of the socio-political and administrative spaces and the rising anti-Muslim hatred are another electoral advantage for the NDA.

The cash transfer scheme was announced just a few days—the proverbial 11th hour—before the enforcement of the electoral code of conduct. The Election Commission of India has been facing charges of being partisan towards the NDA, even in terms of the chosen dates of enforcing such codes. Nevertheless, I, as someone who has been teaching postgraduate students on the history of post-Independent India, would like to draw the reader’s attention to a fact that a marked degeneration in this regard began from the Local Area Development Scheme (LADS) funds given to the legislators. This scheme was an immoral, unjustifiable but a legalised version of bribery to the legislators. This policy had found its way against the backdrop of horse-trading of parliamentarians done by the minority government of P. V. Narasimha Rao (1991-96). This has turned the legislators into executives who entrench their clout by awarding contracts of developmental works to their workers. This is a legalised subversion of the separation of power between the legislature and the executive. Conceiving, drafting and debating bills to enact laws today no longer remains the priority of a large number of legislators, nor is this role expected much by a large number of the electorate. These schemes—engraving names of the legislators in stones and plaques and displaying these across buildings, roads and streets—have become obnoxious obsessions. This has also helped create personality cults, thereby subverting the process of democratisation.

Fear of the hegemony of the Yadavs among the Economically Backward Classes (EBCs/Ati-Pichhdas), non-Yadava Other Backward Classes (OBCs) and the Dalits has not abated. Nitish Kumar’s visibly deteriorating health is a cause for worry for the EBCs. They have sympathy for Nitish who has done a lot for them in his earlier stints. That the Muslim electorate didn’t stay with him for long is another story. Even more important, but less articulated and least appreciated aspect is: Nitish has been the only force standing between Muslims and a complete saffron hegemony over Bihar’s administration. Academically and otherwise, this will remain an arguable point as to whether Nitish’s politics would be seen more as an enabler of Hindutva or as a thin, fragile wall between the Muslims and Hindutva? Arguably, it is a bit like the ‘half-filled or half-empty glass of water’.

The saffronisation of the socio-political and administrative spaces and the rising anti-Muslim hatred are electoral advantages for the NDA.

Tejashwi Yadav’s hugely attended, vocal and assertive mega rallies have further created a scare among some sections of the EBCs and Mahadalits. So they are silently rallying behind the NDA. Why silently? Bihar demography is unique in the sense that most of the constituencies have a sizeable population of the M-Y. A considerable number of the seats have got a minimum of 30-40 per cent of M-Y. They make Tejashwi’s rallies demonstrably spectacular. The M-Y has got a good proportion of panchayat representatives due to reservations for the EBCs and a chunk of Muslims comprise the EBCs. They are upwardly mobile, “neo-rich”, and aspirational. Hence, they have become campaigners, slogan shouters, political workers and booth managers. Remittance money from West Asian countries and a growing affluence of a segment of Muslim artisans and skilled workers—motor and puncture mechanics, electricians, masons, plumbers, taxi drivers—in the post-liberalised era has created a new scenario. They are more vocal than their predecessors. They have an urge for announcing their arrival in terms of their newly-acquired economic status. In order to show it, they demonstrate their identity and prosperity through bigger, brighter mosques with taller spires (minaar) and bigger domes (gunmbad) in their villages and mohallas. In graded South Asian societies, when the poor and the subjugated become affluent and powerful, it is resented even more by the historically dominant classes. There is a popular saying in Hindi-Urdu: log apney dukh se kam dukhi hotey han; doosron ke such se zyadah dukhi hotey hain (People are less troubled by their own privations, they are more troubled when others, hitherto poor-disadvantaged, become happier).

These upwardly mobile Muslim subalterns—vis-à-vis their corresponding Hindu counterparts—also offer economic rivalries in mohalla-based local trading as much as in funding and affording the election expense for local bodies. This makes communalisation of electoral politics much easier and helps the saffron outfits build a narrative among the subaltern Hindu communities: “Look! How the Islamic countries of the Middle East have worked towards the economic upliftment of the Indian Muslims, the mlechhas or yavanas (non-Hindu foreign descents).” This strikes a chord with the subaltern Hindu communities and the saffron politics thrives on it. This helps gloss over the deprivation, subjugation and marginalisation of these communities. It dispenses with making the ruling dispensation accountable to the subaltern Hindu communities on the front of development (vikas) and good governance (sushasan).

In such a scenario, the once aspirational Muslim youth have become more vocal towards narrativising iqtidaar mein hisseydaari, apni qayadat (proportionate share in power, our own leadership), so the saffron task of consolidating Hindus has become much easier. Of course, the scary stories of Muslim repression from states such as Assam, Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand, have created a wider disjunct between the common Muslim electorate and the aspirational, upwardly mobile youth narrative-makers on social media. Common Muslim voters are less likely to get swayed by such slogans of their aspirational youth. In such a scenario, a legitimate aspiration will not be disapproved by the common Muslim electorate, yet a majority of them will decide their electoral preferences much more cautiously. Thus, even though Asaduddin Owaisi’s oratory finds a nod and approval from a section of the Muslims, a chunk of them choose not to endorse and articulate it through their votes. Such “minoritarian” politics—from Seemanchal (Kishanganj, Purnea, Araria, Katihar) in east Bihar to Jalle (in Darbhanga, the Tirhut-Mithila sub-region of north Bihar)—of mobilising Muslim votes more explicitly in campaign speeches has its own immediate and long-term implications.

Liberalised economy, growing inequality and social tension, and the resultant identity politics remains an academic debate even while it is playing out in the starkest ways on the ground today. Nevertheless, it warrants a deeper attention of the pollsters and social scientists alike as to why is the Bihar regime incumbent since 2005, mobilising on vilifying (or villainising) a regime which has been non-existent for the last 20 years? Doesn’t the incumbent NDA regime have something more concretely positive as its performance to showcase than the crassest and possibly short-lived populist welfarism to contest this election?

In a curious mix or cocktail of crime and communal mobilisation, the NDA campaigners have been harping on Osama Shahab, the son of a deceased gangster-politician, Mohammad Shahabuddin (1967-2021). In September 2016, while articulating my outrage against treating gangsters as role models by the aspirational youth of the respective castes-communities, I had written, in a column, “The Cost of Worshipping Gangster”: “Adulation of goons by their community is a manifestation of despondency as fans have nothing more to look forward to as symbols of their pride. The moot point is whether the common Muslim of Siwan has started identifying himself with the goon as this would make them vulnerable not only to crime, but possibly also to violent religious extremism.”

The Lalu-Rabri regime only changed the social composition of the gangsters. Their regime added some subaltern castes into the world of the gangsters and politicians.

But the point here is, is it a Muslim-exclusive phenomena? Certainly not! This was/is certainly not only a Muslim phenomenon. At least since the 1970s, every other dominant caste/community has got its own “dons” and outlaws to worship and to elect them to enact laws for the land and its people. For instance, since the 1970s and the 1980s, Muzaffarpur was lorded over by many gangsters and warlords. Stories about them need to be explored deeply, and told widely. One such ‘don’, Raghunath Pandey (1922-2002), went on to become a minister in the cabinet of Satyendra Sinha (1917-2005) in the late 1980s, about whom, he later recorded, in his Hindi memoir, Meri Yaadein, Meri Bhoolein, that morally this was one of the most unpleasant decision he had to take. Mainstreaming political criminals is a story that is more than half a century old in Bihar.

In the Bihar Election 2025, even within the opposition RJD, Osama Shahab (Raghunathpur, Siwan) and Shivani Shukla (Lalganj, Vaishali) are contesting from their respective seats with the same symbol. (Please don’t miss the irony that Vaishali is touted as the birthplace of proto-republicanism in the ancient period). The social media narratives, the socio-political narrative-making elites and the electoral gossip of the pro-NDA electorate have varied responses. Their narratives burden Osama with the misdeeds of his deceased father. The same is not the case when they discuss about Shivani Shukla, the UK-educated daughter of a convicted gangster, Munna Shukla, now serving a life sentence. This in itself reveals a lot about the duplicity of the pro-NDA electorate and their narrative makers.

Moreover, the “amnesty” granted to the convicted gangster, Anand Mohan Singh, by the Nitish-led administration, in a clearly dubious manner, and nominating his son, Chetan Anand, as JD-U’s candidate, too is not a concern for the pro-NDA electorate. Shukla and Singh are convicts of spectacular murders, respectively, of high-profile people such as a Dalit IAS officer-cum-DM of Gopalganj, G Krishnaiah (1957-1994), and a gangster-turned-minister, Brij Bihari, whose widow Rama Devi has been a BJP parliamentarian from Sheohar Lok Sabha constituency more than once. Of course, a spectacular broad daylight murder of Dularchand Yadav in Mokama, on October, 30, 2025, allegedly by the JD-U nominee and infamous gangster-legislator, Anant Singh, is not outraging the NDA supporters. The fact that Prashant Kishor Pandey and the cadres of the Jan Suraaj Party are not expressing adequate outrage over the murder of its supporter, a Yadav, also says a lot about casteist prejudices in general, and the anti-Yadav sentiments of the Bhumihars in particular.

Such religious and caste-based partisan response to gangster politics tells unfortunate stories about our society and polity. Thus, communalisation of crime, or the four Cs—communalism, casteism, crime and corruption—continue to be the four banes of Indian society and polity. Ever since Bihar was declared a dry state by Nitish Kumar, almost every panchayat of Bihar has propped up a hoodlum or a criminal linked to the liquor mafia with vicious protection and patronage from legislator-politicians and the police. This corrosive phenomenon remains awfully underexplored by the academia and the media alike. This has led to a more dangerous nexus between the police-liquor mafia and politicians. Right now, this is the biggest problem of Bihar, but no one is paying adequate attention to this gravest of problems.

The criminal justice system that manifests itself by the willful failure of the police in preventing crime; in finding and producing evidence before the judiciary to book the culprits; and, in not protecting witnesses, is a perennial failure of Indian democracy. With communal hatred peaking to an unprecedented scale, along with the complicity of the police with the criminals who are aligned with the ruling dispensation, the social fabric is in tatters.

In communalised and casteist narratives of electoral campaigns (and of the “everyday communalism”, as put by Sudha Pai-Sajjan Kumar, a professor), there is a willful and selective amnesia on the part of the pro-NDA narrative-makers. The pre-1990 or pre-Lalu Bihar was no heaven. The US-based political scientist, Harry W. Balir, has written unambiguously in one of his academic essays that the Bihar Legislative Assembly may have been captured at gun point by gangsters had it been an independent country. Needless to add, Blair talked of the pre-Lalu Bihar. So, what did the Lalu-Rabri regime do? They only changed the social composition of the gangsters. Their regime added some subaltern castes into the world of the gangsters and politicians.

Sample this quote from Arvind N. Das’ (1949-2000), The Republic of Bihar (1992):

...The state has been carved out into zones of influence of local ‘leaders’, mostly with daunting criminal records. Many of them are MLAs: some are ministers. From Mohammed Suleiman’s territory in Kishanganj through Pappu Yadav’s domain in Purnea-Madhepura, one can cross Bihar by passing through Anand Mohan Singh’s area and then into the realm of Raghunath Pandey and ‘Samrat’ Ashok and further into the Gopalganj belt of Salaluddin and the Wild West of Champaran. Alternatively, one can go through Makhi Paswan’s Khagaria, Kailu Yadav’s region, into the Dularchand tal and then through Dilip Singh’s land and on to the lawless Kaimur ranges crossing the realm of Surendra Yadav. Other routes are equally dominated...”

All this could sound hackneyed to anyone who knows a bit about Bihar. The 2025 election has not been able to project any leadership or a chief ministerial face who could be looked upon to take the benighted land of Bihar out of its morass. There’s also the Jan Suraaj of Prashant Kishor, which can be an effective spoiler—possibly damaging the RJD and the JD-U more than the BJP. This resource-rich new political formation might emerge in the near future as a short-lived force in Bihar, just like Arvind Kejriwal, who had a brief stint in Delhi.

To people like us, sadly, the polity of the “Internal Colony”—that is Bihar—therefore, still has a long time to wait before any good can be ushered to its people.

(Views expressed are personal)

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Mohammad Sajjad teaches modern and contemporary history at the Aligarh Muslim University.

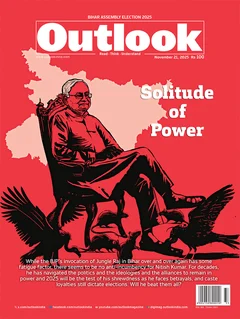

This story appeared in print as 'A Morass Of Lies, Deceit And Red Tape' in Outlook’s November 10 issue Solitude Of Power, in which we trace Bihar’s enduring political grammar, where caste equations remain constant, alliances shift like sand, and one man’s survival instinct continues to shape the state’s destiny