The RSS Shakha used physical activities and Baudhik (intellectual) sessions to instill a narrative of Hindu unity, glorifying Hindu history while ignoring caste oppression and marginalizing anti-Brahminical thinkers.

Figures like Savarkar, Golwalkar, Shivaji, and Rani of Jhansi were celebrated, while reformers, the Indian Constitution, and leaders like Ambedkar and Nehru were minimized or vilified. Myth and history were blended to create a strong ideological identity.

By adolescence, the author embraced radical Hindutva, but a warning from local authorities initiated a decade-long process of unlearning and critically reflecting on how OBC youth are drawn into Hindutva networks.

My Pune of the 1990s was not the “Oxford of the East”. It was across the Mula-Mutha River, in its underbelly: Yerwada, Nagpur Chawl, Housing Board colonies, and Ambedkar Nagar. These were neighbourhoods of Dalits, Bahujans, Muslims, and Christians, stitched together with narrow lanes, tin roofs, broken drains, and a stubborn will to live. For upper caste Pune, Yerwada evoked only three images: the Cellular Jail, the Mental Hospital, and the Bahujan slums. To them, we were the muck of the city—unseen, unnamed, and best left forgotten.

Outside our basti, India itself was in turmoil. The Babri Masjid lay in rubble, Kashmir convulsed with militancy, and Mumbai reeled from Hindu-Muslim riots and serial bomb blasts. Bal Thackeray was reinventing himself—from “Marathi Hriday Samrat” to “Hindu Hriday Samrat”—stitching Shiv Sena’s nativism to the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) Hindutva political project by mobilising the Ma-Dha-V formula (Mali, Dhangar, Vanjari castes) in Maharashtra.

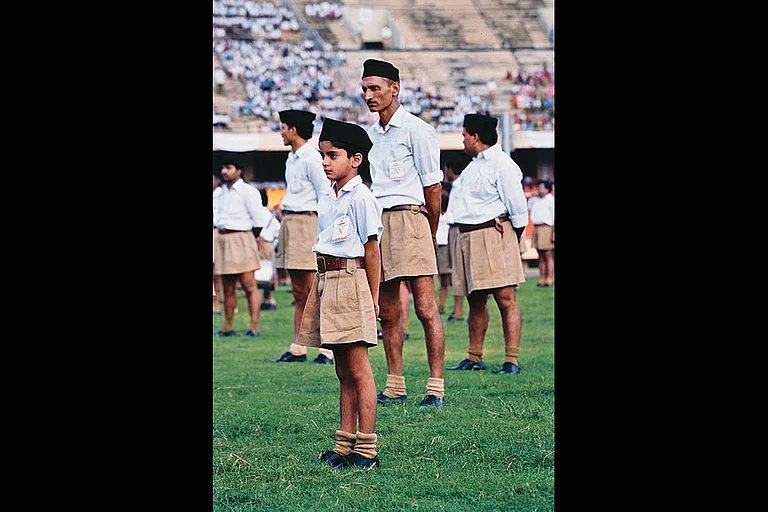

Meanwhile, Pune was also transforming. IT parks rose in Hinjewadi and Kharadi. The road past Yerwada Jail, once burdened with stigma as “Jail Road”, was rebranded as “International Airport Road” to erase that shame. But inside our basti, history arrived as rumour and riot—from milk-drinking Ganesha idols to mobs smashing Muslim-owned hotels over the loss of India in the India-Pakistan cricket match. Other devastations were quieter, more cruel: HIV-AIDS hollowed out families, while women were burned alive for dowry demands, their deaths dismissed as sudden “kerosene stove explosions”. It was in this atmosphere that my family introduced me to the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) shakha. They believed a Brahmin shikshak (teacher) would instil “better sanskars (manners)” in me, protecting me from the chaos of our immediate world.

Today, the cost of this OBC Hindutva indoctrination is not only cultural, but intergenerational in nature. Without recovering from non-Brahminical social and cultural memory, OBC masses risk being weaponised as Hindutva’s surplus army.

Inside the Shakha

Initially, the physical games and songs of the shakha drew me in. But it was the Baudhik (intellectual) sessions that captivated me. There, one truth was drilled into me: we were Hindus above all. India—Akhanda Bharat—was always a Hindu Rashtra, once a glorious civilisation, later enslaved by “foreign invaders”: Muslims and Christians. Caste reality had no place in this narrative. The caste-based humiliations and inequalities structured into Hindu society—even in my basti—were never discussed. Instead, Hindu unity against Muslims and Christians was offered as the cure for the ‘Hindu Weakness’. In RSS Baudhik, any reference to the Indian Constitution was absent. B. R. Ambedkar, Jyotirao Phule, and Periyar were erased from historical discussions in our Baudhik. If Ambedkar appeared in discussions as a passing remark, it was only as a “Dalit politician” who drafted the Indian Constitution, not as the radical thinker who dismantled Brahminical hegemony. His conversion to Buddhism was reduced to merely adopting another “sub-sect” of Hinduism. Instead, the Shakha fed us hagiographies of Savarkar, M. S. Golwalkar, and K. B. Hedgewar. Shakhas celebrated Chhatrapati Shivaji, Sambhaji, Peshwa Balaji Vishwanath, Rana Pratap, Rani of Jhansi, and Guru Govind Singh as great heroes and prophets of Hindu Rashtra who protected Bharat Mata from the external aggressors. Shakhas promoted the cultural and civilisational ideas of Vivekananda, Ramdas Swami, and Aurobindo as crucial for developing the ideal patriotic character of the Shakha swayamsevak. We were told to accept our dutiful obedience to the ‘guru’—the ‘saffron flag’, as an ultimate symbol of Hindutva. Anti-Brahminical saints and reformers such as Tukdoji Maharaj, Sant Gadge Baba, Kabir, and Bulleh Shah were overlooked. In the Shakha, Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, and M. A. Jinnah were vilified as architects of Indian Partition, at the same time, Netaji Bose and Sardar Patel were praised for their armed militancy and strong actions against Muslim rulers such as the Nizam of Hyderabad and the Nawab of Junagadh. Muslims in Baudhik were treated selectively. Ashfaq Ullah Khan, A. P. J. Abdul Kalam, and Shahid Abdul Hamid were celebrated as patriotic “good Muslims”, while others, like artist M. F. Husain, were demonised. Myth and history blended seamlessly in Baudhik, where the Ramayana and Mahabharata were presented as factual accounts of Indian history. By 15, I had devoured writings of Savarkar, Golwalkar, Hedgewar, and even Hitler’s Mein Kampf in Marathi. I called myself a ‘Kattar Hindu’ (staunch Hindu) and started attending cultural programmes like ‘Shastra Puja’ (weapon worship) of radical Hindutva organisations in Pune. My indoctrination was complete—until the day the local police intelligence warned my father to watch his juvenile son before he “goes astray”. That shock began a decade of unlearning—through reading, reflection, and a growing awareness of how countless OBC (Other Backward Classes) youth like me are drawn into Hindutva’s orbit.

The RSS and ‘Samrasta’

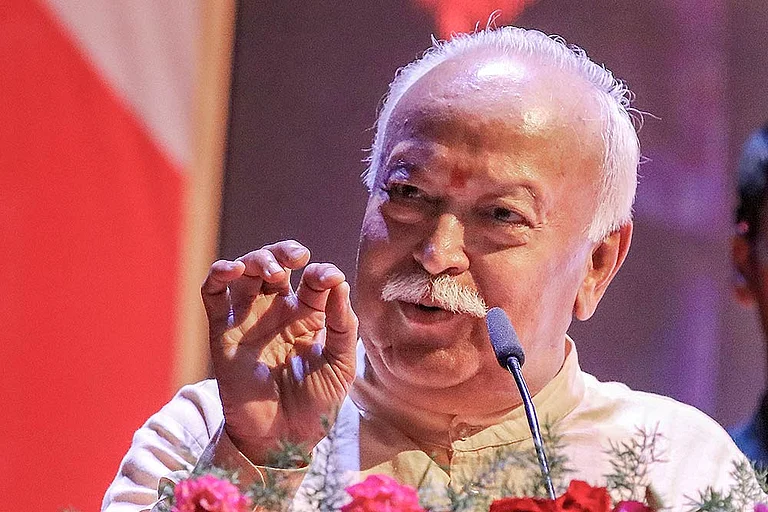

Today, as a public policy scholar, I know my story is not unique. Many OBC youth walk the same path. That is why, as the RSS marks its centenary, it is vital to examine its worldview through an OBC-Bahujan lens. In his centenary speech, RSS Chief Mohan Bhagwat reiterated the principle of Samrasta (social harmony). Symbolic gestures—“one temple, one waterbody, one crematorium”—were presented as progressive steps to erase caste discrimination. But these do not touch the deeper power structures of caste, like ownership of land, political power, social privilege, and economic dominance that continue to remain with the upper castes. Samrasta assimilates Bahujans into the Brahminical fold, while leaving caste hierarchies intact. Bhagwat also affirmed support for Scheduled Caste/Scheduled Tribe (SC/ST) constitutional reservations, but remained evasive about OBC reservations and the caste census. The RSS has registered the ‘calculated response’ towards the OBC caste census. It has historically opposed OBC reservations as outlined in the Mandal Commission report. Such measures would reduce the hegemonic grip of Hindu nationalistic fervour on the OBC masses. His defence of traditional Hindu religious texts in the speech revealed another contradiction. He argued that such texts no longer shape the daily life of ordinary Hindus. But one should note that these very religious Hindu texts sanctify caste, and their reverence as “sacred traditional Hindu wisdom” provides ethical legitimacy to practice caste inequality in the mind of the everyday Hindu. Protecting these religious texts from rigorous intellectual inquiry, in effect, protects the caste system itself.

The OBC Crisis of Social Memory

The RSS did not emerge in a vacuum. Its rise was born of upper-caste anxiety about India’s shifting social, cultural, and political order over the past two centuries. Its success lies in building parallel institutions—schools, cooperatives, banks, media, think tanks, cultural bodies—that penetrate the daily life of the Bahujan masses. The BJP leverages the groundwork of RSS institutions to an electoral advantage, transforming cultural hegemony into political state power. But the deeper crisis lies within the OBC social memory. A substantial segment of Dalit politics today inherits and asserts a self-confident Ambedkarite narrative of social and political change. However, many OBC communities still lack that independent social, cultural, and political imagination. The Phuleite, Ambedkarite, and Periyarite legacies—along with broader non-Brahmin, anti-caste and religious civilisational strands—remain fragmented or forgotten within the larger OBC society. This vacuum allows the RSS-BJP to capture OBC social and political imagination with the myths of Hindu Rashtra and Akhanda Bharat. Today, the cost of this OBC Hindutva indoctrination is not only cultural, but intergenerational in nature. Without recovering from non-Brahminical social and cultural memory, OBC masses risk being weaponised as Hindutva’s surplus army—mobilised to attack Dalits, tribals, and religious minorities, while themselves remaining subordinated under Brahminical order as ‘Shudra Slave’.

The Task Before the OBC Movement

The RSS Brahminical worldview rests on a zero-sum vision of its cultural, social, and political dominance over Indian society. Drawing on Patanjali’s metaphor of the natural rivalry between ‘snake and mongoose’, it frames Brahminical and non-Brahminical traditions as locked in perpetual civilisational enmity. From Savarkar to Golwalkar to Deendayal Upadhyaya, the Hindutva project has insisted that Brahminical culture must dominate, supersede, and co-opt every other social, cultural, and political identity that can provide an alternative imagination for the Indian society. Behind the rhetoric of “Hindu unity” lies a project that mobilises Bahujan society as foot soldiers, while denying them independent social assertion. The challenge for OBC politics is not merely electoral—it is civilisational. The RSS thrives on OBC amnesia, offering borrowed pride in Hindu identity in exchange for complete obedience. To break this cycle, the OBCs must reclaim their social, cultural, and political histories, draw strength from non-Brahminical anti caste thinkers like Mahatma Phule, Ambedkar, Lalai Singh Yadav, and Periyar, and create parallel institutions that anchor anti-caste consciousness in everyday life. Schools, cooperatives, media outlets, and cultural spaces must become sites of both learning and resistance for OBC society against the RSS Brahminical Hindutva indoctrination. Intellectual labour—through research, translations, media, and museum archives—must spread self-assertive Bahujan thought to the new OBC generations. OBC political leadership must move beyond transactional seat-sharing to the harder, slower task of educating and inculcating a collective Bahujan conscience among the OBC masses. Without this, the OBCs risk settling permanently into the role of a ‘Shudra Underclass’ in a Brahminical Hindu Rashtra. The survival of Indian democracy itself—its promise of social justice and equality—depends on whether OBCs can recover their rightful place in Indian national life and boldly reimagine India’s ‘Bahujan future’. Ambedkar once said: “Tell the slave that he is a slave, and he shall revolt against his slavery.” That is why he wrote his book ‘Who Were the Shudras?’—to awaken the OBCs from their Brahminical caste slumber. His words remain alive and continue to inspire future generations of the OBC masses in their effort to imagine a free, democratic, secular, and modern India for all.

(Views expressed are personal)

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Anand Kshirsagar writes at the intersection of politics, culture, and economics of OBC communities