A 2020 study in the Population Research and Policy Review journal found that self-reported mental health scores among Scheduled Caste adults were worse than those of upper-caste Hindus, even after adjusting for asset distribution and education levels.

Dom Community face untouchability and are shunned by the rest of Varanasi city. Their work of lighting funeral pyres with unwashed corpses carries obvious dangers. One study notes, “burning the bodies is a difficult task that involves various risk factors that directly affect their health.”

Manual scavengers are at grave risk, and studies show that these people have an increased morbidity and mortality rate due to frequent drownings in septic tanks, toxic gas exposure and resulting chronic infections in the body.

A human corpse burns at 1,000 degrees Celsius. A living human exposed to such heat can watch their sweat vanish before it can drip, their skin singe, and their hair curl and sear at the edges. Burnt to a deep brown, with hairless arms and chest, Shalok Chaudhry lights funeral pyres for about “30 to 100 bodies a day” on a slow day. Visible burn marks stain his fingertips.

Chaudhry laughed at the sores on his hands. “I get burnt here and there because I have to move through the pyres and arrange the wood to make sure all the bodies are burning properly. It happens,” he said, scoffing at his injuries.

One of roughly 200 Dom workers who stoke the Hindu funeral pyres at the Manikarnika Ghat in Varanasi, Chaudhry works under Dom Raja Om Chaudhry and his nephew Shalu Chaudhry. The 32-year-old once used to work as a government clerk. “I knew I had to come back eventually and do this work. I would think about it often, and I think people sensed it too, so I gave it all up and moved back to fulfil our caste’s duty. Every one of us has to do this, no matter what else we do,” he said.

As the sun sank into the Ganges, Manikarnika Ghat was awash with activity and desperate people. It is the day’s final hour in which a Hindu funeral pyre can be lit. Bodies wrapped in saffron cloth are laid out on bamboo rafters. At any given moment, five or six bodies crackle in the fire, consigned to flames that rage as hot as between 5,000 and 6,000 degrees Celsius.

Chaudhry is taking a break from his shift. He has been here for two days lighting funeral pyres for people who bring their dead from across India and “sometimes even from abroad.” With a soaking wet gamcha (a traditional cotton hand towel) on his shoulder and the scent of ash and burning flesh clinging to his person, Chaudhry takes measured sips from a five-litre plastic water bottle, sharing it with other community members working that day. He inherited this world the moment he was born into the Dom caste, a community entrusted with sending the Hindu community’s dead to moksha, the final liberation.

Chaudhry sees his work as both his sacred duty and an unremitting trial of his body. As he leaves the sanctuary of a makeshift sitting room the Dom workers have made for themselves, he prepares to re-enter the sizzling pit; a world of flames, stigma, exclusion and stress.

Fire and Isolation

Chaudhry’s grandfather too made a living from stoking pyres; his father did too. Every day for the past five years, Shalok has followed in their footsteps, pulling on a thin, cream-coloured crochet shirt—no protective equipment beyond a gamcha—and being the final port of call before “souls” get moksha. He does not remember a sunrise that did not burn his lungs, nor a single day free from heat so intense that it has branded his skin.

In his village, an hour from Varanasi’s ghats, Chaudhry said his children must prepare for the same life. He hopes for better for his seven-year-old daughter because “women cannot do the work of a Dom.” He said it with a touch of relief, then added with quiet pride that he sends her to a private school. But for when he has a son, Chaudhry said the boy will “have to come here at least once a month to learn our sacred duty—no matter what job he decides to do full-time.”

Drinking Away the Deathly Stench of Indignity

Doms face untouchability and are shunned by the rest of Varanasi city. Their work of lighting funeral pyres with unwashed corpses carries obvious dangers. One study notes, “burning the bodies is a difficult task that involves various risk factors that directly affect their health.”

To withstand the smoke, the stench of burning flesh and the weight of centuries of stigma, many from the Dom community drink. They turn to country liquor when they must and to foreign brands when someone offers them. Chaudhry also drinks sometimes but insists it is nothing serious or habitual. “It stops us from dehydrating,” he said. Other members who sit in the circular sitting area nod along in agreement.

A 2025 survey of 75 Dom workers found that 76 per cent of them regularly consume alcohol or smoke before work to “keep themselves in a state of mental unconsciousness,” because “it is not possible to live with dead bodies forever with a stable mind.”

“It gets so hot in that pit that I cannot breathe; so hot that I feel like running away and jumping into the Ganges,” Chaudhry added.

His nights are restless; his blurry dreams are fitful, filled with flames and fumes. Come morning, he wakes up coughing, but shoulders squared and large, deep-sunken eyes all-seeing a world that sees him as no more than a burner of their dead.

In India, his experience is not unique.

A 2020 study in the Population Research and Policy Review journal found that self-reported mental health scores among Scheduled Caste adults were worse than those of upper-caste Hindus, even after adjusting for asset distribution and education levels. Researchers Aashish Gupta and Diane Coffey concluded that caste discrimination itself inflicts a form of chronic psychological trauma, driving rates of anxiety and depression sharply upward among the most marginalised communities.

An Overwhelming Allostatic Load

Allostatic load is a chronic stress-induced depletion of a human body’s ability to run its core systems. This shows up in people as high cortisol levels, compromised immune systems and accelerated ageing.

In India, where caste hierarchies continue to dictate the daily lives of many, the allostatic load that Dalits, tribals and Other Backward Castes (OBCs) bear is intense. A 2024 rapid scoping review showed how prolonged caste-based public condemnation produces hormonal dysregulation and causes “weathering” in members of marginalised communities.

In a 2024 survey of women living in Mumbai slums, SC/ST community women had the highest Kessler Psychological Distress Scale—a popular tool for measuring non-specific psychological distress—scores. Despite the fact that the slum-dwellers had similar socioeconomic plights, the women with SC/ST backgrounds reported twice the levels of anxiety and depression as their general caste neighbours. The study said the women’s triggers ranged from direct caste violence to the everyday indignities of being treated as an “untouchable.”

Not Allowed In: A Rickshaw’s Life

Ravi Kumar is only 25 years old but carries the load of a family of seven. He pumps the pedals on his bike-drawn rickshaw through Varanasi’s labyrinthine alleys. The eldest of four siblings, a Chamar by caste, Kumar is denied entry to the temples to which he ferries devotees who flock to the ‘holy city.’ He was only 13 when his mother was bedridden due to a botched C-section while birthing his youngest sibling. The tween watched his mother bleed all over their home—“She would try to cook food for us, but the floor underneath her would be red with blood.”

The family went into debt to raise money for his mother’s treatment. Kumar was sixteen when his father had his first heart attack. “The doctor told us not to give him any tension because a second attack would kill him,” said Kumar. The family fell into debt—owing over Rs 21 lakh for treating his mother’s postpartum issues and his father’s heart. Kumar recalled having to go over to neighbours’ houses to beg and borrow essentials like salt, flour, even vegetables. He dropped out of school to support them. “I knew, I could see, that if I didn’t start earning,” he says, “we would be on the streets.”

Now, Kumar carries four to five passengers at a time, pedalling until his quads bulge and tremble from the effort. By nightfall, he is so tired and his back and legs ache so much that he says emptying a whole bottle of country liquor is the only way to numb himself. He wants a different life for his infant daughter and his younger sister, whom he is putting through college. “She wants to open a salon,” he said. “I want her to have choices I never had.”

He’s embarrassed by his alcohol intake. “Before starting work as a rickshaw driver, I would not even take a sip of daaru. Now, I need it. I could finish a whole bottle in one evening.”

Substance use is often a survival mechanism for people for whom mental health services have failed. A 2024 study found that Dalit or tribal people have to endure insults and violence so often that the sustained psychological stress response increases, drastically, their levels of anxiety, depression and, consequently, substance use.

An analysis conducted in 2024 found that caste-based violence, social exclusion and widespread alcohol use are perceived as major contributors to psychological distress in lower-caste households. The women of the community were triply discriminated against—belonging to a lower caste, due to their gender and because of their economic status.

The Sewer That Ate An Entire Family

In Delhi, the Rohini Basti slum barely registers amid skyrise apartment complexes mushrooming in the district. Inside a maze of waterlogged lanes and exposed electrical wiring, brothers Dharmveer and Karmveer labour in stench and sewage. The pair are manual scavengers who, despite a 1993 Supreme Court order banning the practice, clear untreated sewage by hand. Their father and eldest brother died inhaling lethal gases during their work shifts. Dharmveer is educated till the third standard and Karmveer till the eighth.

“Sometimes people will get their drains cleaned and then when we ask for money, they shoo us away, saying they’ll call the cops. what have we done wrong to ask for money we have earned?”

Dharmveer, 38, and his wife and five children live inside a 50-square-foot room, while Karmveer, 30, lies on a cot opposite his elder brother’s bed, battling a chronic respiratory infection he contracted six months ago while working without safety gear. “I feel like a burden,” Karmveer whispers, his body bent forward like a question mark—he has no idea when he will get better and be able to become a productive member of this family.

During parent-teacher meetings at his children’s schools, Dharmveer listens silently as teachers at the private schools his daughters attend—thanks to the Economically Weaker Sections (EWS) scheme—tell him they need tutors outside school to help with their homework.

“I cannot help with their homework. I studied only till class three. I don’t have the money to pay for tutors,” he said. His eyes are large with mortification as he added, “If I cannot even provide for my daughters, I feel worthless.”

The Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavengers and their Rehabilitation Act, 2013, expanded the definition of manual scavenging and mandated rehabilitation measures for those engaged in the work. However, to date, an estimated 90,000 workers are engaged in manual scavenging, mostly Dalits. Manual scavengers are at grave risk, and studies show that these people have an increased morbidity and mortality rate due to frequent drownings in septic tanks, toxic gas exposure and resulting chronic infections in the body. The National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) has repeatedly ordered that such workers be given more protective gear such as gloves, masks, training and health check-ups, but as the brothers would tell you, enforcement remains a pipedream.

Barriers to Care

Across these three documented lives of the Chaudhrys, Kumars and brothers, Karmveer and Dharmveer, one stark fact emerges: mental health care infrastructure for India’s marginalised castes is non-existent. Stigma around both caste and mental illness then makes for a double bind that they must free themselves from without any external help. Chaudhry does not believe anyone will be able to help him. “No one can understand what we go through because no one has had to live it,” he said. Kumar almost laughed at the idea of seeking mental health services. “I don’t have money for a normal doctor!” he says.

The National Family Health Survey and the National Sample Survey collect health data, but rarely is it aggregated by caste except for mortality and nutrition metrics. Mental health policies, then, are framed without caste-based data.

Some NGOs do step in to fill the gap. Based in Mumbai, Sangath has a pilot community counselling programme in the city’s slums, which is unique in that Dalit and tribal volunteers are paired with mental health professionals to aid counselling. Breakthrough, in Delhi, has peer support groups for women survivors of sexual and caste-based violence. Blue Dawn is, however, the only mental health community that is run by community members to aid others. Health economists have often pointed out that there would be a high return on investment in community-based mental health programmes, especially if they were integrated with India’s pre-existing public health infrastructure.

The Cost of Silence

Ignoring caste as a health determinant has a high cost. Exposure to chronic stress leads to cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, autoimmune disorders, and harmful substance use. Depression and anxiety affect even the children, who have a hard time with schooling and thus their future prospects, leading to a seemingly endless cycle of poverty and exclusion.

Since 2017, NITI Aayog, with assistance from the World Bank, has set up a health index initiative to measure the performance of the states and union territories. The most recent index report, released in 2021, does not include any mental health indicators or those that consider caste, gender and geography. The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare issued guidelines for the Mental Health Care Act of 2017, but implementation has been uneven across states.

Dignity As A Fundamental Right

Chaudhry, Kumar, Karmveer and Dharmveer struggle to live on a day-to-day basis. Dom workers make about 400–500 rupees daily; Kumar earns about Rs 1,000 on a good day of pedalling people on his rickshaw, and the brothers get a few hundred bucks if they are lucky. They said, “Sometimes people will get their drains cleaned and then when we ask for money, they shoo us away, saying they’ll call the cops… what have we done wrong to ask for money we have earned?”And yet, when they speak of their children, their voices shift, steady and almost matter-of-fact, as if hope, however fragile, remains a habit they are unwilling to break.

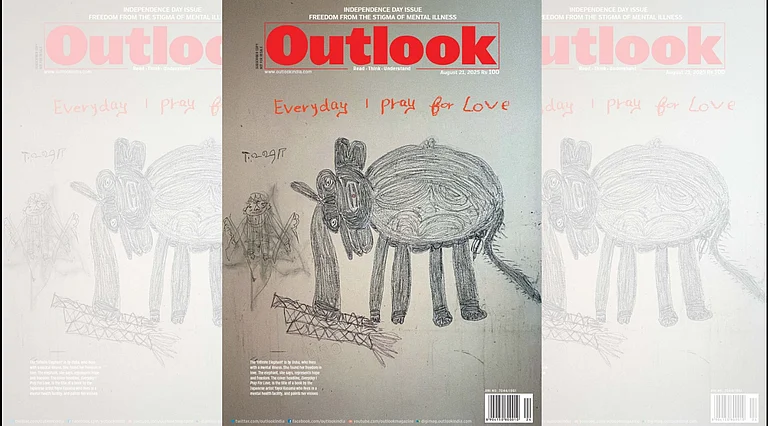

In its August 21 issue, Outlook collaborated with The Banyan India to take a hard look at the community and care provided to those with mental health disorders in India. From the inmates in mental health facilities across India—Ranchi to Lucknow—to the mental health impact of conflict journalism, to the chronic stress caused by the caste system, our reporters and columnists shed light on and questioned the stigma weighing down the vulnerable communities where mental health disorders are prevalent. This story appeared in print as Annihilation of Dignity.