Santosh Nagoji takes a deep breath and walks toward the hole-in-the-wall men’s salon on a Thursday evening. He needs a haircut but dares not enter the 10 x 10 sq feet parlour, painted with pink walls, and take up the empty seat next to two customers. He knows what the barber’s response will be. Standing at a distance from the salon’s threshold, he still curtly asks, “Kesa kapnar ka (will you give me a haircut)?”

The hairdresser is about to nod when a customer getting a facial stops him. Taking one look at Nagoji he coldly says, “Dalit aahe toh (he is a Dalit).”

In most places, barber shops serve as a space for grooming, hygiene, occasional gossip, and social interaction. For Nagoji a well-built 33-year-old from the Mahar caste, who works on contract as a delivery driver in Mumbai, it is an everyday place of exploitation, discrimination, and humiliation. A place to avoid, a no-go zone.

“No haircut for Dalits,” a strictly enforced caste-based prohibition, is a custom, zealously practised in the village of Nagansur, Tondlur, Navindagi and others in Solapur’s Akkalkot taluka on the Maharashtra-Karnataka border. The dominant caste of Lingayats—a politically strong community—maintains an upper hand over the scheduled castes of Mahars, Matangs, Dhor and Chambhar living in these villages. In Nagansur of the 8500-odd population, Lingayats constitute the majority and only 1500 are scheduled castes and tribes. They treat members of Other Backward Castes (OBCs) and Muslims as relatively equal citizens. Dalits, however, are ostracised; haircuts in barber shops being one of the examples.

This practice is one of the 400-odd documented forms of untouchability followed in different parts of the country, as per Ghanshyam Shah edited 2006 book, Untouchability in Rural India.

“The country has got freedom, but not us. Our situation is still like being under gulaamgiri (slavery),” says Gadeppa Sharanappa Chikkali, sitting under the shade of a leafy Banyan tree, next to the memorial of Babasaheb Ambedkar. He was born in Nagansur, in 1946, a year before independence. The village followed stringent rules of segregation and untouchability even then.

Dalits could not walk close to non-Dalits; they had to keep their gaze lower and address all upper caste gentry including children with respect as Patil. There were separate containers for water and tea at corner shops, which Dalits had to wash and clean after use. “Even at that time, the barbers did not cut our hair. We would do it ourselves at home,” he says touching his overgrown mop under a Gandhi cap.

No haircut for Dalits, a strictly enforced caste-based prohibition, is a custom, zealously practised in solapur.

Many of these laws were forced out of practice in the 1980s after a group of young Dalits inspired by Bahujan Samaj Party founder Kanshi Ram’s fight, formed the DS4 group or the Dalit Shoshit Samaj Sangharsh Samiti, (Dalit and other Exploited Groups Struggle Committee) in Nagansur. A lot has changed since then, and yet, a lot remains the same. The deprivation of a mundane service like haircuts, in today’s times, serves as a living reminder to the Dalits of their past, villagers say.

“They want us to stay suppressed like the way our ancestors did,” says 22-year-old Sachin Bargale, a young student about the abhorrent practice. The only difference in the oppression and discrimination today is that it is practised with caution and fear of a political and legal crackdown. “Aamne saamne bhedbhaav karat nahi, he asa lapun chapun kela jaata (they don’t discriminate openly, but covertly),” he says.

Official data from Solapur police show an estimated 35 cases monthly and close to 250 cases annually are registered in rural areas under the SC & ST (Prevention of Atrocity) Act 1989. The offences range from casteist slurs, abuse, rape, molestation, threats and violent assault.

No one in the village knows the roots of the custom of banning Dalits from getting a haircut, except that it has been in practice for decades. The discriminatory tradition, a form of contemporary untouchability, is rampant in the southern part of Solapur and Karnataka, where Lingayats are the majority population.

“Nahi katate woh baal. Hamne bohot baar poocha (they don’t cut our hair, we asked them many times,” says Tukaram Vhatkar, a young man from Dhor caste, a community of tanners. He is watching the drama featuring Nagoji unfold at the salon. None of the three barber shops in Nagansur, which charge Rs 40 for beard and Rs 50 for haircut, will serve Dalit men. For a trim or shave, young boys and men travel 12 kilometers away to the town of Akkalkot or Mashal, the first village across the Karnataka border.

The barber Shivsharan Hadapad, arrived in Nagansur a year ago from Hossur in Karnataka. As he was new, Vhatkar tried to get a haircut inside the salon, taking advantage of his lack of knowledge about the village customs. To his disappointment, the owner of the salon had coached Hadapad not to cut Dalit men’s hair.

30 per cent of households in rural areas and 20 per cent in urban areas reported practising untouchability.

Ironically, the barbers belonging to the Hadapad sub-caste are backwards too. Yet, they do not hesitate to follow communal diktats from the Lingayat strongmen. Their placement within the Lingayat community lends them a higher status than the Mahars and other Dalit castes. The 12th century Lingayat sect also has a rich history of secular reforms by its founder Basava who rejected gender or social discrimination, and caste distinction. In a battle of hierarchies, among Lingayats, Hadpads and Mahars, the formerly untouchable marginalised community is located at the very bottom.

The practice of untouchability was the primary reason Ambedkar, born in the Mahar caste, opposed Hinduism. Mahars traditionally lived outside the villages and performed duties of securing the village perimeter, arbitrating village conflicts, sweeping streets and clearing animal carcasses. In medieval times, under the Peshwa rule, they were treated as outcasts and regarded as untouchables for eating meat. Ambedkar called villages a cesspool of cruelty and discrimination and advised Dalits to move to cities.

The first Law Minister and lead author of the Constitution converted to Buddhism in 1956 with millions of Dalits in Nagpur. As per the 2011 Census, of the eight and a half million Buddhists, nearly six million are based in Maharashtra.

Untouchability was practised against the lower castes for close to 3000 years in India. Its existence in today’s time in the form of restrictions like, no entry in salons, or temples is not surprising, says Amit Thorat, professor of Economics specialising in social exclusion and inequality at the Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi.

The first documented case of caste discrimination was in Maharashtra in 1847; it’s about a young Dalit boy who wanted to study in school but had to sit outside the class. In 1949, the Constitution outlawed discrimination and untouchability against the scheduled castes, giving equal status as a citizen to all. Reservations further ensured positive affirmative action towards the historically backward castes. But, the notions of purity and pollution are still very much entrenched socially among the non-Dalits, he adds.

“Just because untouchability was abolished on paper doesn’t mean it does not exist in practice. Just because there are laws and constitutional provisions, doesn’t mean they can change the 3000-year-old social mindset. Just because we don’t see it with our eyes, doesn’t mean the practice doesn’t exist,” Thorat says.

The practice of untouchability existed for a longer period than African American slavery which lasted for around 400 years. While the former is based on a person’s descent and the other is on race, both forms are similar to the extent of human exploitation, Thorat emphasises.

His research and studies on caste dating from the Vedic period to independence, and physical surveys, indicate the continued prevalence of the practice of untouchability in various forms in all the villages across India.

His findings of the India Human Development Survey of 2011-2012, a joint study by the US based University of Maryland, and the National Council of Applied Economic Research, Delhi, show that 30 per cent of households in rural areas and 20 per cent in urban areas reported practising untouchability. Hindu households did not approve of lower caste people entering their kitchen or using the utensils.

“In villages, social relationships are historically defined on caste lines and these traditions are passed on inter-generationally. It is hard to break them,” he says.

In Nagansur, for instance, the ban on cutting hair as a practice of untouchability is imposed against Dalits openly in broad daylight. Less than 20 meters from Hadapad’s salon, across the main road, stands the local police chowki of Nagansur village.

In cases where Dalits are denied haircuts, one can file a police case under the Atrocities Act. However, no such cases have been filed on the matter in Nagansur to date.

“It’s a matter of village-level politics. Some try to give it a different colour. But there is no conflict. Everything is sorted and peaceful,” said Vilas Yamawar, Deputy Superintendent of Police, Akkalkot, Solapur. He denied the existence of the practice as there were no recorded complaints.

An estimated 35 cases monthly and close to 250 cases annually are registered in rural areas under the SC & ST Act 1989.

A former police superintendent disclosed that during his tenure at Nagansur, he could not break the black law, despite being a member of a scheduled caste. “I’ve suffered caste discrimination myself and I’ve seen the discrimination here. Nowhere else in Maharashtra I’ve heard or seen about such oppressive practice,” he says. The PSI held meetings with the non-Dalit villagers in an attempt to reach an understanding of the haircut conflict. But failed in his efforts as the Lingayat community held steadfast to their tradition, as an age-old practice, he adds.

The PSI as well as Dalit activists, and senior police officials fearing the law-and-order situation, resist registering written complaints and rely on verbal counselling. The punishment for offenders, if found guilty under the Atrocities Act, is minimum six months imprisonment. The law can be stringent, but the repercussions towards the Dalits for breaking established caste-based norms can be fatal.

All barbers collectively shut down the shutters of their shops for seven days, after a Dalit teacher reported the prohibition to the Tehsil authorities prompting a visit from government officials to the village. “They will never do anything that can catch the attention of the authorities. They hide their acts and feign complete denial if the district officers, police or even outsiders ever investigate this matter. The tyranny is reserved only for Dalit villagers like us who they know by name and our identity,” says Ganesh Chinwar, a dynamic political activist at the forefront of the fight against caste discrimination.

At the Gram Panchayat office in Nagansur, inquiry about the practices leads to a village elder stomping out. Other men sitting outside the mosque and a school denied the existence of any discrimination against Dalits.

Rajkumar Gurav, a police constable from the village, said there was unity among everyone. “I have Muslim and Dalit friends, we all help each other,” he insisted. When asked about the caste restriction on salons, he drew a blank response.

Chinwar has written numerous letters and held demonstrations with the district and police authorities against the oppression of the Lingayat community. But the casteism persists.

Every year the Dalit and Lingayat villagers come head-to-head in April on Ambedkar’s birth anniversary. Dalits are denied permission to carry celebratory procession on the day in the village’s main jurisdiction. Gram Sabha members have cited the nuisance of loud DJ sound systems, flaying of gulal, fireworks and damage to the narrow roads as reasons for the refusal of permission for a procession to honour Ambedkar.

“The worst part is that police and district collectorate officials tend to side with the upper caste people and ask us to not conduct the celebration. Even when there is police bandobast, there’s a riot-like situation,” he says.

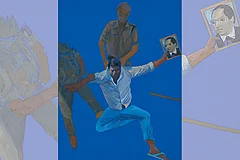

Even when the procession is by foot, with Dalits carrying Ambedkar’s photo in hand, the atmosphere turns volatile, as it did this year. A mob surrounded the procession , and threatened it with loud sloganeering as it tried to peacefully enter the village’s main entrance. This resulted in chaos and arson.

Men are not the only ones to face the axe of social divide. Women and children speak about another layer of the abuse, humiliation and discriminatory treatment meted out to them.

Mahadevi Lakshman Munderkiri, a 36-year-old mother and farmer, seethes in a rage talking about the use of separate drinking water pots for Dalits, a practice unknown in her native village in Solapur. Labourers belonging to the Dhangar caste working as contractors on her two-acre farm carry separate water pots, one for themselves, and the other for people like her. “It is my farm, but when I go to work there, they will not give me water in a glass. They will pour it in my hand. I have to carry my matka,” she says.

“Aamhi shivleli bhakar aani aamhi shivlela paani, chalat nahi (they won’t accept roti or water touched by us),” adds Basvalinga Pote. She recently returned to the village from Mumbai after working as a domestic help for over a decade, the kind of job she could never bag in her village.

In the city, no one asked for her caste or treated her as an untouchable. “Mahars are not allowed to enter the main village so how can they allow us into homes?”

During summer and in times of water scarcity when the source of the well in the main village runs dry, non-Dalit women come to the Dalit vasti to fetch water from the handpump. “They will shoo us away from the hand pump and only then draw the water,” she says. The women have come to accept these practices as their protests and opposition yielded no change.

Seven kilometres away, in Tondlur ,the last village on the Maharashtra border is also in the throes of casteism, though the villagers deny it. The rules of this village also prohibit Dalits from getting any service from the barbers and from entering the local temple. Every January, the village hosts the popular Siddheshwar temple fair, attended by hundreds of outsiders; however, local Dalits are asked to stay away.

“We are not keen to visit the temple. But even if we try, they will fight with us,” says Basvaraj Walikar, an SC Gram Sabha member.

Satish Shinge once playfully entered the Shiva temple to ring the bell and was shooed out. “The old man sitting inside shouted abuses at me and I ran away,” he says adding that he and his friends have also been to the jatra.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

The 12-year-old does not know the concept of jaati or which divide he belongs to. But at his tender age, he has certainly even if in all innocence, broken free of the caste shackles. The elderly sitting around him, who have suffered the burns of casteism, wished it was that easy.

(This appeared in the print as 'No Haircut for Dalits')