Freedom won after fighting a long battle against colonialism and the constitutional republic established after India secured independence, how far has its fruits reached the masses of the working population today? The history of unfreedom and bondage in employment in India is associated with the wretched institution of caste-based bondage.

The rigidity and hereditary reproduction of caste-based bondage relations in employment have been codified in the Manusmriti and have been practised since ancient times. The expectation that analysts like Karl Marx had of colonial intervention in India and of capitalist relations playing their role in transforming the caste-based oppression and unfreedom, did not quite materialise as a consequence to the cozy partnership between the feudal elements and the colonial rulers.

The labour supply was being done by the local feudal elements to the plantations, which were set up by the East India Company and such other colonial entities. Dr Baba Saheb Ambedkar fought throughout his life for the annihilation of caste-based segregation, unfreedom, humiliation and exploitation. While such traditional caste-based bondage has been abolished by law after independence, its practice has acquired new forms and continues to pose a challenge.

While in post-independent India a variety of State interventions, economic development as well as political resistance have certainly reduced the capacity of traditional caste-based institutions to enforce control and exploitation, these very sections of society, which find themselves at the bottom of the social as well as the economic hierarchy continue to experience what scholars like Jan Breman have called “neo-bondage”.

Neo-bondage is not associated with traditional cultural institutions but rather with economic transactions and markets. Whereas wage labour is seen as a form of employment where workers have the freedom to choose or even change their employers in the eventuality of unacceptable terms of contract or treatment meted out to them in the process of labour activity, neo-bondage effectively deprives workers of such freedom. This is happening in a variety of sectors, including international labour migration and employment.

We are focusing on domestic labour relations here. Within India, unfree labour is found especially in the unorganised sectors such as the construction sector and related activities, such as brick kilns. It is also found in some forms of high-valued commercial crop agriculture-labour relations. In such forms of employment, the victims are usually caught in cycles of chronic indebtedness.

This distress generates conditions that produce and sustain unfree employment relations. This is best illustrated by the case of brick kiln migrant workers from the most backward areas of the country; in Koraput, Balangir, and Kalahandi in Odisha to peri-urban pockets of Telangana and other states, the poorest of the poor borrow money from local money lenders at a whopping 10 per cent monthly interest rate, which compounds every six months.

The poor who are predominantly the landless as well as marginal and small farmers belonging to Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes as well as some sections of Backward Castes, are mired in such grave poverty that they need to borrow credit from local money lenders even to meet basic requirements. Once they take loans, since the poor lack the capacity to repay based on what they can earn from the employment available in Odisha, they borrow advances from contractors who recruit labour for working in brick kilns.

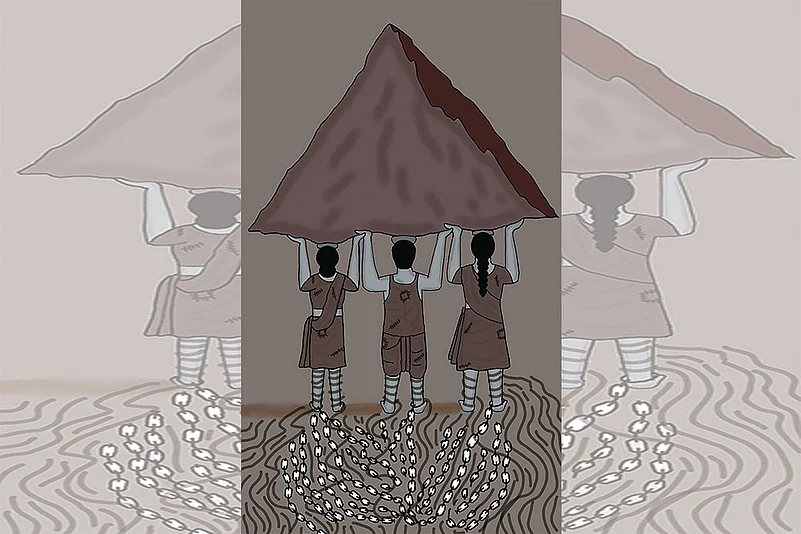

The recruitment happens around November and brick kiln work continues until June. A patri consisting of three members of a family is recruited by paying an advance amount of about Rs 45,000. Once this advance is paid, the wages earned from the brick kiln work are effectively seen as getting tagged to the repayment of this advance payment the workers received. This intricate relation of repayment of the advance amount through wages effectively converts the status of employment into a bondage relation.

The workers are made to slog for 16 hours daily from 3:30 in the morning to 10:30 at night. In the anxiety to extract the maximum value for the outstanding advance amount, which the worker has to repay, the contractors use verbal abuse, physical violence, sexual exploitation and violent modes of supervision and extraction of work.

Workers are forced to toil even when they fall sick. To ensure that the repayment of the advance received by the workers, the contractors have evolved such institutions as the village committees in the places of origin of these workers, hired railway police officials, and the mafia at the transit points of travel and the local police and local mafia at their destinations, through systematic bribes and commissions.

If workers run away from the work places to escape from the atrocities, these agents help to trace the workers and handing them over to the contractors. Most of these workers are not registered, while the law requires that they be registered since every licensed labour contractor has to, as per the law, comply with limits on the number of workers he/she can recruit.

However, labour contractors recruit many more than the permissible numbers and avoid the mandated payments to the government, which are calculated per worker recruited. On the other hand, even when a variety of activist organisations (Labour Help Line for instance) identify the existence of such forms of bondage, revenue officials are usually reluctant to file a case of bonded labour. This is partly because the agency meant to enforce the Bonded Labour Abolition Act would have to admit it failed to do its job, if it registers a case. There is a need to separate these functions.

Apart from the bondage associated with advance payments, there are other forms of unfree employment relations associated with insecurity of employment as well as with employers’ uncertainty of assured supply of labour.

Workers have been found taking loans from employers in a desperate attempt to ensure that because there is a loan outstanding, they will not be fired. On the other hand, in organised manufacturing industries, especially during peak seasons, contract workers who are recruited by middlemen contractors are paid delayed wages.

The wage payments which are to be paid at the end of the month are given in the middle of the next month. As a result, at any given point in time, workers have wages pending for the work rendered. If they quit, it is at the risk of foregoing their wages. This is done to ensure supply of labour and prevent labour turnover. These examples are only the tip of the iceberg with reference to forms of unfree labour, which continues to be a matter of concern in independent India. There is documented evidence of young female workers belonging to Scheduled Tribes from Jharkhand being recruited by agencies to work as domestic helpers, and then forced into sex work.

In more recent times, forms of unfree employment can also be seen in high-valued employment. Freedom from employees’ vantage point is associated with leisure time.

In several forms of information technology-related activities, the concept of work time has become fluid. In addition to the formally contracted work timings, there is an informal ‘availability’ of the employee, which is being practised.

This implies that at whatever time a client (usually located in foreign countries) tries to contact the employee over mobile phone, the employee has the obligation to attend to the call. The fact that leisure time is intruded into can be seen as a violation of freedom. This is because, conceptually, working time is associated with a definite quantity of wages/salaries, working time/day characterised as ‘‘toil, trouble and unfreedom’’, away from leisure, associated with the freedom and self-determination in the use of time.

Problems of work-life balance, as well as workplace surveillance, which often intrude into personal life as well as choices (including marriage, pregnancy, etc.). Consequentially a variety of health disorders, especially stress-related psychological issues and disturbed family and community relations are seen as being closely correlated. India has to address this ugly side of its reality due to informalisation and deregulation of the labour market and engagement in flexible labour market practice in the name of ease of business and incentives, which are leaving large sections of citizens unfree. Failure to respect freedom could produce a culture of consent for authoritarian regimes, which have no respect for individual liberties or collective freedoms. Freeing our labour force could well be the fulcrum of protecting India’s independence and the rights it has secured for us.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

G Vijay is faculty, School of Economics, University of Hyderabad

(This appeared in the print as 'An Unequal Republic')