On a May afternoon at a Lucknow brick kiln, 25-year-old Mithilesh and his wife were dragging themselves to set the layers of brick moulds. High fever was not letting them walk. In the scorching heat, with burnt legs, heavy heads and dizzy vision, they were stumbling upon the stacks of bricks. They could barely hear the voice of their one-year-old who was crying uncontrollably, lying inside their temporary brick shelter that felt like a ‘furnace’. Still, they must hunch over to set the layers—they have to make 1,000 bricks a day—to get Rs 50. Or else, they must sleep hungry, and their child would perhaps ‘die’. Neither could they leave the place nor could they ask for relief—they were ‘bonded labourers.’ He didn’t know any other way of living—for generations, his forefathers have been working as bonded labourers at the local zamindar’s land. And now, it was his turn.

Mithilesh and his wife, along with their two children, had been taken away by a contractor to Lucknow from Gaya in Bihar for a paltry advance of Rs 2,000. They were asked to work until they repaid the loan. However, even after working day in and day out for 10 months, their loan was not repaid. “We used to start work from 2 am and had to work up to 10 pm to produce at least 1,000 bricks. Only then, they would give us Rs 50 for the daily meal. But as per their promise, they were supposed to give us Rs 200, but they used to keep Rs 150 per day as instalment for the loan,” recalls Mithilesh, standing near his mud house in Bargaon village of Gaya district.

When they used to fall sick and could not work, the contractors would get medicines for them. “Kaam kar lo nahi to khoraki nahi milega (work or else you will miss the daily allowance for meal),” they would say. One of their children, who was three then, also worked with them. “These children used to turn over the bricks during the drying process. Their light weight came in handy,” says another worker who used to work in a different brick kiln and didn’t wish to be named.

The misery of Mithilesh’s family neither starts with him nor does it end with his children. They have been working as ‘bonded labour’ since forever. Even if they get free from physical bondage, their caste forces them towards different forms of despondency.

Belonging to the Mahadalit community known as Rajbanshi, his predecessors served the local landlord from the Bhumihar caste for decades. “When I got married and came here, I discovered that my in-laws worked at the fields for the landlord. I joined them. For everyday work—sowing the seeds, watering plants, separating the chaff from the grains—we used to get one kg of grains,” says Dulari Devi, Mithilesh’s mother, now in her 70s. After the day’s work, she used to spread her koycha and the Bhumihar’s man used to give her grains. They were given a small piece of land for accommodation. Later, Mithilesh got to know from court records—with the help of some social activists—that their forefathers had around 10 decimal land that was deceptively grabbed by the upper caste landlord. “It is still in our name. Nobody ever sold it to him. They gave us one-tenth of our own land for accommodation and asked us to work for him against it!” says Dulari. Now, a case is going on over the land dispute, but they have already grabbed a part of the land.

In the early 2000s, Dulari informed the landlord that she wanted to work elsewhere as it was impossible for her to feed her seven children with the limited grains she was getting. “After hearing this, he hit me with a plough, and I got 20 stitches. I couldn’t leave from there. Even the police asked me to work there,” she says.

***

Though the bonded labour system was abolished in 1976 through the Bonded Labour System Abolition Act, 1976, it is still prevalent across the country. People from the lower castes living in the interiors of Bihar, Odisha, Jharkhand, Rajasthan, Assam and several other states are taken away to faraway places against some paltry advance and forced to work until they repay their loans.

As per the Act, bonded labour is defined as “the system of forced, or partly forced, labour under which a debtor enters, or has, or is presumed to have, entered, into an agreement with the creditor to the effect that in consideration of ‘advance’, ‘customary obligation’, or any other form, “render, by himself or through any member of his family, or any person dependent on him, labour or service to the creditor, or for the benefit of the creditor, for a specified period or for an unspecified period, either without wages or for nominal wages.”

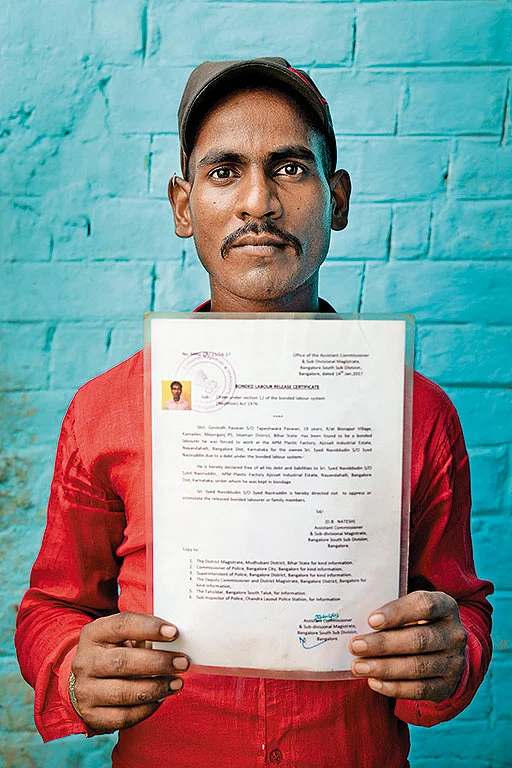

In 2016, while responding to a question in the Rajya Sabha, the Ministry of Labour and Employment said that they had rescued/rehabilitated 2,82,429 people from bonded labour. It also promised to rehabilitate and release around 18.4 million bonded labourers by 2030, leading to its abolition.

In 2021, the government notified the Central Sector Scheme for Rehabilitation of Bonded Labourer-2021, increasing the earlier rehabilitation amount, and adding provisions like a piece of land and a house for the family of the rehabilitated labourer.

Currently, bonded labourers get a one-time help of Rs 30,000 from the government after their release. Earlier, they would get Rs 20,000. Later, upon the conviction of the employer, they are entitled to get Rs 1 lakh for males, Rs two lakh for women and children and Rs 3 lakh in extreme cases of sexual trafficking and sexual bondage of women, children or transgenders.

A social worker who is engaged in the rescue of these labourers says on condition of anonymity: “While the district magistrate or the SDM is responsible for recognising them as bonded labourer, they don’t want to do it. In most cases, they don’t give them certificates of bonded labourers, depriving them of the basic rehabilitation facilities that they are entitled to”. Even after 48 years of the Abolition Act being passed, things have not changed on the ground.

Elaborating on the importance of the abolition of the bonded labour, David Sundar Singh, a lawyer in the Tamil Nadu High Court, says: “The Act was passed during the emergency and had a lot of potential. However, over the years, the character of bonded labour has changed, and it has merged with human trafficking. So, changes are needed in its formulation.”

Under the act, the maximum punishment for an employer stands at three years whereas for human trafficking it is not less than five years in prison and this can be extended to seven years if it is a case of child trafficking. In this context, Singh says, that the employers must be tried under the Human Trafficking Act as well.

The major change in the character of bonded labour, as witnessed in recent times, is related to the ‘advance’ paid to the labourers. “Earlier, labourers were paid an advance and were forced to work as bonded labourers but now, some contractors promise labourers that they will be employed for two-three years and would be paid the total amount at the end of the term. These labourers are forced to work for the same owner and freedom of employment is denied to them,” adds Singh. But what forces them to remain trapped in such bondage? Extreme poverty, lack of government support and caste oppression make this population vulnerable to easy luring.

***

On a moderately cold February morning in Chennai, in a room occupied by around 60 people, 11-year-old Gautam woke up and looked in the direction of the window. The bustling city was largely unseen from where he was sitting but he had pinned his hopes on the few scattered shops and pedestrians. He wanted to ask for help. “Neither could I scream, nor could I call out to anyone for help because of the language barrier. I was also scared. I had witnessed the locals beating us up.” The window couldn’t bring any respite to his life. The sounds of machines and the continuous pressure to stitch chains of school bags that a child of his age would carry to school made his life unbearable. He wanted to go back home. He wanted to see his mother. But didn’t realise that he was asking for ‘too much’ as a bonded child labour.

Belonging to the Mushahar Mahadalit community, Gautam was taken away by a trafficker around September 2022 to work in a bag factory in Chennai. He was just 10 then.

Extreme poverty, lack of government support and caste oppression make the economically and socially deprived population vulnerable to easy luring.

The family of six— three brothers, one sister and parents—live in absolute destitution in Rupauli village in Sitamarhi district of Bihar. His father was a contractual labourer—barely managing to arrange for two meals a day. A mud hut with a roof made of hay and straw tied to bamboo poles is what they call ‘home’. As one peeps into their kitchen—an extension of the house—one can’t even find basic utensils. Storage of food items or vegetables is a faraway dream. “People belonging to the mostly landless Mushahar community barely manage one meal a day,” says a social activist.

“I was in Class 5 when an uncle from the adjacent village came and told us that we would get to earn if we went to Chennai with him. My parents didn’t want me to go but all my friends were going, so I went,” says Gautam. A total of 16 children from the village were taken to Chennai’s bag factory. They were crammed into a general compartment and were given only samosas in their 48-hour-long journey. As soon as they reached Chennai, Gautam realised that there would hardly be any chance for him to escape.

On his first day, he slept through waiting for a chance to call his parents. The next day, he started working. “I was missing my mother. I requested them to let me talk to her once, but they called her only after a week. I cried and told her that I am in Chennai and requested her to take me back. She could hardly say anything and kept crying.”

Wiping her tears while remembering those horrific days, Gautam’s mother says: “We told him not to go. When we got to know that he was working in Chennai and wouldn’t be sent back home, we were broken. But we didn’t know where to go for help or which door to knock on. The contractor told us that he was safe and would be sent back after a year. He also promised a salary of Rs 3,000 per month, but that Gautam never received.”

Two houses away from Gautam, stays Lalit. His home situation is the same as Gautam, but he was the most vulnerable among the children, making him easy prey for the contractor. “His mother killed his father, and she is now in prison,” informs a neighbour. Since then, he has been growing up at the mercy of his relatives. When the contractor came, it was easy for him to woo Lalit, they add.

Amid this crisis where fear dominated their everyday lives, Gautam found his own space of relief—perhaps the only way to cope with the uncertainty of life. “Twice a month, our Sardar used to take us to the beach. I used to love playing with the sand. I still remember those days,” says the teenager while sweating profusely in the unbearable July heat. Due to the dearth of electricity, food and basic amenities in their own village, the muggy wind blowing by the beach gave them respite.

While Gautam, after his rescue, got a certificate and the one-time assistance of Rs 30,000, his family has not received the piece of land or a house as promised in the new rehabilitation package.

There are three major factors that drive traffickers to target certain communities—financial impoverishment, caste identity and the relationship between the trafficker and the trafficked.

When we went to the block office of Bathnaha under whose jurisdiction Rupauli village falls, Rajaram Paswan, the current BDO, said that he had taken charge just a few days ago. The next day, he personally went to survey the houses and informed us that the children and their families would be rehabilitated, and their education would also be taken care of.

However, the infrastructural condition of the government middle school at Rupauli where Gautam, Lalit and other children have been readmitted after their rescue is too poor to even deliver basic education. With no fans and lights in the classrooms, eight teachers are delivering lessons to more than 360 students. While the physical education teacher was teaching mathematics, the headmaster, Shambhu Saran, was busy accusing the community (the Mushahars) of a lack of interest in studies. “We can’t run behind the students. Their parents don’t take care of them. They are drowned in alcohol addiction. What can we do? Still, we are trying,” he says. Rupauli village consists of extremely marginalised communities like Mushahar, Fakir, Yadav and Kushwahas.

After their readmission, Gautam, along with his friends, were directly promoted to class eight. On being asked whether he could add eight and nine, he was silent. However, when he was asked to add Rs 8 and Rs 9—his response came fast—“Rs 17”.

“Their life is all about working relentlessly on others’ fields or factories and thus they can only count when it is asked in monetary terms,” says a local activist.

Around 15 km away from Rupauli, at the margin of Singhrahiya village, Deepak and his mother couldn’t even keep their rehabilitation amount as the contractor came and snatched it. Deepak was taken away to Chennai by one of his brothers’ acquaintances named Abulesh. He was crammed into a school bag production unit with at least 15 other children. “I used to oil the machines and cut stitches from the bag. I cried everyday but no one was there to help us. I couldn’t leave. They told me that I had to continue working there as long as they wished me to,” says Deepak.

But even after his rescue, his misery hasn’t ended. “We got Rs 30,000 from the government but soon after Abulesh came and forced us to give that money to him. He said that he had to bear the loss due to the court case he had to fight. We went to the police, but Abulesh threatened my elder son, and we withdrew the complaint,” says Deepak’s mother.

Deepak lost his father two months ago and now their livelihood depends on the meagre wage that his mother earns working at others’ agricultural land. His father lost his vision while cutting rice around ten years ago. “Since then, we used to get a disability pension. After his death, even that has stopped,” she adds. They also haven’t received the promised land and the house. Notably, Deepak’s family belongs to the Chamar caste that falls in the SC category.

So, there are three major factors that drive traffickers to target certain villages and communities. The first factor is financial impoverishment, the second factor is their caste identity and the third is the relationship between the trafficker and the trafficked. “In most cases, you can see that the trafficker knows the trafficked. It becomes easy for them to lure them away against some advance,” says a social worker on condition of anonymity.

***

The rehabilitation of bonded labourers, however, has not been successful in most cases. Rameshwar Teli, the former Union Minister of State for Labour and Employment, in his written reply to the Lok Sabha in December 2023, noted that the government has given assistance of Rs 43.65 lakh to rehabilitated bonded labourers in Bihar in 2021-22. The amount of assistance was increased to Rs 58 lakh in the next financial year. Still, people like Mithilesh are not even receiving ration under the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana (PMGKAY).

“Neither did we get money for a pucca house, nor did we receive the monthly ration. Our families have been into generational bondage for decades but there is no one to take care of us,” Mithilesh quips while saving himself from the raindrops incessantly pouring through the leak in the roof made of straw. The double whammy of bondage and caste never left them.

After he received the one-time assistance, he opened a small shop selling samosas in the village. But that was burnt down by the upper caste people of the village. We tried to reach the mukhiya of the village who didn’t show up for a comment. Ajay Paswan, the sarpanch of Mataso, under whose jurisdiction the village falls, says that it is the responsibility of the mukhiya to look into such matters. We reached out to Rahul Ranjan, the BDO of Fatehpur block, who promised to register Mithilesh and his family members under different schemes. The next week, Mithilesh confirmed that the BDO contacted him and asked him to come to the office to process the applications.

While rehabilitation has been a continuous matter of concern for the government and other stakeholders working in tandem to abolish the bonded labour system, in a few cases, they have managed to change the lives of the rescued labourers.

Govind Paswan, 25, lives in Bishanpur Kamdeo village in Sitamarhi district. He was taken to Bengaluru by his uncle and was dumped in a 20/10 foot room where machines and sacks of plastic granules took away the carpet area—leaving hardly any space for them to sleep or breathe. The dark, dingy, claustrophobic room with its faded walls from where layers of plaster were coming out like skin flakes became his home in bondage. The blue iron door that was locked all the time until they were rescued—only to see the sun after eight months—made it a ‘cage’.

Their physical bondage turned out to be more brutal with the incessant violence that choked Govind in fear. “I couldn’t say anything to the contractor. The supervisor used to force labourers to urinate on others if they skipped work even for a while. I used to follow his instructions blindly,” recalls a shivering Govind. And when he got the chance to come out of the bondage with the help of some NGOs and government officials—he called it ‘Azaadi’.

After his ‘Azaadi’, he started a small fruit shop and also bought an auto-rickshaw. Last year, he was elected as a ward member of the panchayat. He now asks people to not fall into the trap of bondage for a mere advance. “Be wherever you are and find work. Don’t fall into these traps,” he says.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

The celebration of ‘Azaadi’ for people like Mithilesh, Govind, Dulari Devi and Gautam is freedom from bonded labour—a freedom that they cherish throughout—even in paucity.

(This appeared in the print as 'Of Human Bondage')