1: The initial version of the Bill, which failed to pass in 2024, was reintroduced in December after which the committee received over 12,500 submissions—many from democratic rights organisations offering detailed critiques.

2: These responses questioned the Bill’s necessity and highlighted substantial overlaps with existing laws such as the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967, Section 113 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita and the Maharashtra Control of Organised Crime Act, 1999.

On July 10, 2025, the Maharashtra Vidhan Sabha passed a revised version of the Maharashtra Special Public Security Act (MSPSA), exactly one year after the original draft was introduced on July 11, 2024, by the Shiv Sena-BJP coalition under Chief Minister Eknath Shinde. Initially framed as a response to the perceived threat of “urban Naxalism”, the Bill claimed to address the alleged infiltration of Maoist ideology into urban areas through affiliated organisations offering logistical support and shelter to underground cadres. Citing intelligence reports and seized materials allegedly linked to Maoist operatives, the government argued for a dedicated legal instrument, referencing similar laws in the states of Chhattisgarh, Telangana and Odisha, and asserting that Maharashtra lacked an equivalent framework.

However, from the outset, the political discourse surrounding the Bill has hinged on the ambiguous and contested construct of the “Urban Naxal”—a loosely defined and politically loaded term often used to delegitimise protest, dissent and civil society activity. Although the initial version of the Bill failed to pass in 2024, it was reintroduced in December that year after Devendra Fadnavis assumed chief ministership. A Joint Select Committee, chaired by Revenue Minister Chandrashekhar Bawankule, was formed to examine the draft. The committee received over 12,500 submissions—many from democratic rights organisations offering detailed critiques. These responses questioned the Bill’s necessity and highlighted substantial overlaps with existing laws such as the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967 (UAPA), Section 113 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), and the Maharashtra Control of Organised Crime Act, 1999 (MCOCA).

Despite the volume of feedback, the committee incorporated only three modest changes: a change in the Bill’s title, a reconstitution of the proposed Advisory Board, and an increase in the minimum rank required for investigating officers. The revised Bill passed the Vidhan Sabha on July 10, 2025, and cleared the Vidhan Parishad the following day, amid opposition walkouts and dissenting notes. It now awaits the Governor’s assent.

Legal Ambiguity, Limitless Scope

One of the most visible amendments to the Bill was the insertion of the phrase “Left-Wing Extremism” (LWE) in its title and preamble. The Act now seeks to curb “unlawful activities of Left-Wing Extremist organisations or similar organisations.” While the Joint Committee claimed that this change narrows the Bill’s scope, the Statement of Objects and Reasons remains unchanged, retaining language originally directed at curbing “Urban Naxalism”. This oxymoron—coined by a Right-Wing ignoramus—was used for the ilk of a professor in a B-school who was accused of propagating anti-establishment ideology to his students. The very setting underscores the absurdity of the proposition: that academic discourse in a business school could be construed as support for armed insurgency in the forests.

The term “Left-Wing Extremism” itself lacks a precise legal definition, though it is widely used by the Ministry of Home Affairs to describe Maoist or Naxalite groups—all of which are already proscribed under the UAPA. Even terms like “Maoist” or “Naxalite” remain undefined, as numerous groups identify with Marxist-Leninist ideology without flaunting arms. Yet over time, their criminalisation has become almost self-evident. LWE is no better—its vagueness only compounds the problem. The addition of “similar organisations” further erodes definitional clarity, vastly expanding the law’s scope and allowing broad interpretive discretion by the executive, thereby undermining legal certainty.

The MSPSA marks a shift in the meaning and application of proscription laws—from targeted, exceptional tools meant to preserve public order to routine instruments of political and ideological control.

Crucially, the Act criminalises “unlawful activity” using vague, sweeping definitions, enabling the government to declare organisations unlawful and prosecute individuals for mere association. It empowers the state to seize and forfeit property, and to designate premises as being associated with banned groups. These powers already exist under the UAPA, which not only includes a wider array of offences but also provides a more detailed regulatory framework. The key distinction is that while the UAPA requires central government sanction, the MSPSA allows the Maharashtra state government to exercise similar authority autonomously.

Yet this rationale is legally unconvincing. State governments already possess the power to ban organisations under the Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1908 (CLA), which remains operative. The MSPSA thus appears more as a political instrument than a legal necessity—raising serious concerns about its underlying intent.

The Politics of Proscription

Rather than enhancing public security, the MSPSA reflects a growing trend in Indian legislative practice: the normalisation of banning as a tool of governance. Article 19(1)(c) of the Indian Constitution guarantees the right to form associations, with reasonable restrictions permitted under Article 19(4). However, the proliferation of state-level public security laws, alongside expansive national laws like the UAPA, have effectively eroded these protections.

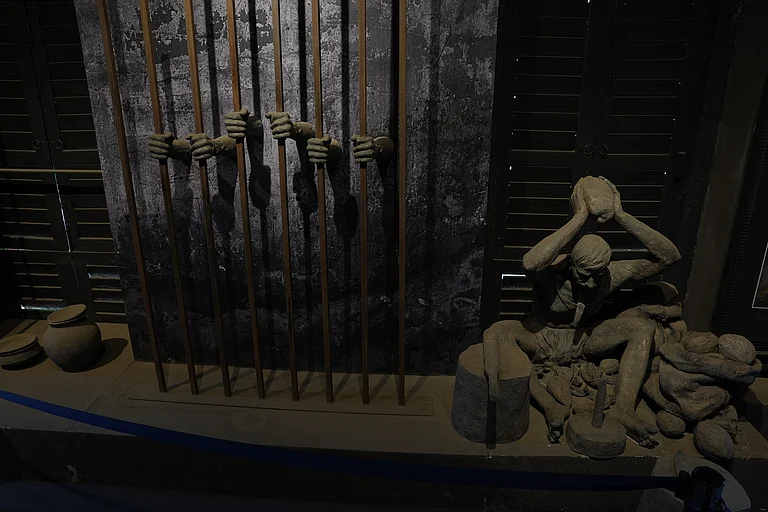

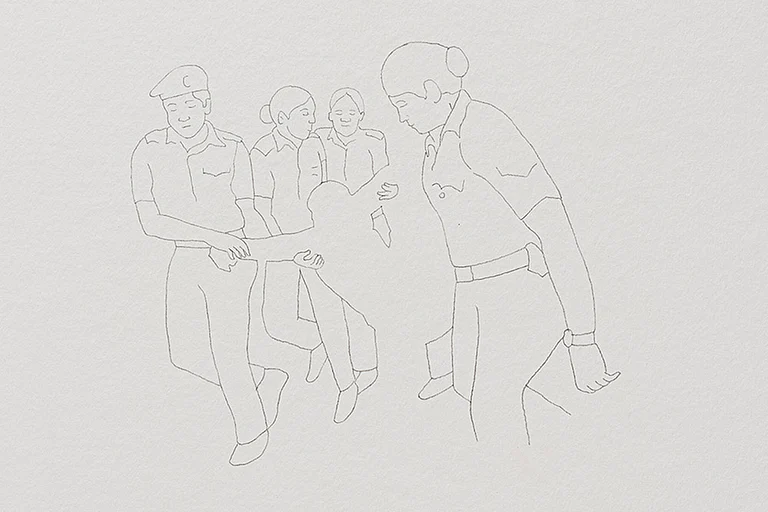

The MSPSA marks a shift in the meaning and application of proscription laws—from targeted, exceptional tools meant to preserve public order to routine instruments of political and ideological control. Increasingly, such laws are not used merely to prevent violence or insurgency, but to curtail the legitimate domain of lawful dissent. The selective application of these laws—often against student groups, academics, journalists and human rights activists—reveals how banning has become a proxy for silencing democratic opposition.

By focusing narrowly on criminalising association and ideological sympathy, the MSPSA enshrines a punitive logic that conflates political dissent with criminal extremism. Its vague language and duplicative provisions are not merely redundant; they are actively dangerous, vesting disproportionate discretionary power in the executive with limited avenues for redress.

A Law Without Necessity

The most troubling feature of the MSPSA is that it attempts to justify itself by invoking threats already addressed under existing laws. The UAPA remains the primary legislation used by Indian authorities to ban organisations, seize assets and prosecute individuals accused of aiding terrorism or insurgency. The Maharashtra CLA, MCOCA and the IPC/BNS already offer supplementary powers to address organised criminal activity. Introducing yet another parallel law muddies the legal terrain and risks legal inconsistency, especially if challenged in the courts.

Moreover, the MSPSA does not establish any new legal or evidentiary thresholds. Its provisions mirror those in other laws but add a new layer of discretionary state control, bypassing central oversight. This may seem like an advantage to a politically dominant state government, but it undermines federal consistency and opens the door to conflicting standards of justice across jurisdictions.

From a jurisprudential standpoint, the absence of a clearly defined necessity test raises red flags. Why legislate again, unless the purpose is not functional but symbolic—intended to signal toughness, intimidate civil society, and brand ideological opponents?

The creation of the MSPSA’s Advisory Board, a body that will review bans and forfeitures, also raises questions about procedural integrity. Though reconstituted to include a retired High Court judge, the Board’s independence is questionable, especially in the absence of judicial review mechanisms that operate automatically and robustly. Further, the burden of proof effectively shifts onto the accused or affiliated organisations to disprove their alleged association with banned groups—a clear departure from criminal law principles of presumed innocence and proportionality.

The notification of premises as associated with “extremist” activity also has far-reaching implications. Such designations can have devastating effects on educational institutions, NGOs, media houses and civil liberties organisations operating in good faith. The potential for misuse is high, and remedies are uncertain, often involving long legal battles against a state apparatus that wields both investigative and prosecutorial authority.

A Pattern of Authoritarian Legalism

The MSPSA fits into a larger national pattern of authoritarian legalism—a mode of governance where laws are not instruments of rights and justice but tools of executive consolidation. Much like the UAPA and the Jammu and Kashmir Public Safety Act, the MSPSA adopts a logic of pre-emptive criminalisation, indefinite surveillance, and expansive interpretation of intent and association.

In this framework, dissent is reframed as deviance; criticism as sedition; solidarity as subversion. The rule of law is preserved in form but hollowed out in substance. The pretext of “public order” becomes a blank cheque for suppressing any challenge to state ideology or authority.

Who is the Public of the MSPSA?

The more pressing question is: who constitutes the “public” that needs security—and from whom? If past experience with draconian laws is any guide, potentially any citizen can be branded, on vague and unsubstantiated grounds, as a supporter of “Left-Wing Extremism” and subjected to the full force of state repression. Such laws manufacture a climate of state terror against individuals who are merely exercising their constitutional rights—freedom of speech, expression, or association. These days, it is the people who need protection from the state’s excesses. What is projected as “public security” thus becomes a veil for shielding those in power from public resentment and questions.

The MSPSA must be viewed not merely as a counterinsurgency measure but in the context of the state’s political economy—particularly urban redevelopment. Mega-projects like the Dharavi Redevelopment, controversially awarded to Adani Realty in 2022, seek to transform informal settlements into elite urban enclaves. Over a million residents face potential displacement, often without clear rehabilitation guarantees. Similar Adani-linked projects in Santacruz have raised alarms over opaque processes and disregard for due process. There may be many such projects and of course industrial ones in the Naxal-cleared areas.

These projects are likely to generate protests and legal resistance from slum dwellers, housing rights groups, environmentalists and grassroots movements. The MSPSA appears designed to pre-emptively criminalise such dissent. Its vague definitions of “unlawful activity” and alleged affiliations with “Left-Wing Extremism” allow the state to arbitrarily proscribe individuals, seize assets and designate meeting spaces or NGO offices as hubs of anti-state activity.

Terms like “right to the city”, “land justice”, or “people’s planning”—central to activist discourse—can be rhetorically weaponised to link movements to Maoist ideologies, thus reframing legitimate civic dissent as a security threat. With the Adani Group closely aligned with the BJP-Shiv Sena government, opposition to its projects risks being delegitimised as subversive.

Such laws enable the state to control narratives, evade democratic scrutiny, and discourage courts or media from engaging with the substance of protest. The MSPSA, then, is not merely a security tool—it is a legislative armature for developmental authoritarianism.

The precedent in Chhattisgarh and Telangana—where similar laws were used against Adivasi leaders and land rights activists—signals the path Maharashtra may now follow. The MSPSA equips the state-corporate nexus with the legal means to impose contested transformations and suppress participatory democracy under the guise of public security.

(Views expressed are personal)

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

This article appeared in Outlook Magazine's 01 September 2025 issue, The Tariff Weapon, as Over Ruled.

Anand Teltumbde is an Indian scholar, writer and human rights activist