Residents of Delhi’s JJ clusters have lived in unsafe, crowded conditions for years, awaiting promised flats.

Policies meant to protect them are poorly implemented, leaving the urban poor marginalized and vulnerable.

Even officially recognised JJ clusters face demolitions, showing systemic neglect and failure to implement in-situ rehabilitation policies.

Behind Gate No. 6 of the INA Metro Station rests a flyover. A road under this flyover leads straight to a row of newly built high rise apartments. Their glass windows catch the sun, and a main gate displays the name of a residential colony that, say residents of Shaheed Arjun Das Camp at East Kidwai Nagar, didn’t exist four-five years ago. They say it was a part of the camp: the site of the only home they have known.

A narrow side path breaks off to the right of the polished gate, leading into the camp. The entry lane is so narrow that even walking through feels like squeezing past walls. Small homes, mostly single rooms, are packed next to one another with no visible boundaries; it’s difficult to tell where one ends and another begins.

Down that path is the edge of a nullah, a drain filled with garbage, black water and plastic waste. The stench is overwhelming but people have built their homes all along it. They live here, getting sick, breathing the air, staying on because there’s nowhere else to go. They have been waiting for their promised flats for the last six years.

Rinki Gupta, a resident of the Shaheed Arjun Camp, said she has lived in the jhuggi for nearly three decades, ever since her marriage. Living on the banks of the Kushak nullah, life can get unbearable. During the monsoon, the water rises so high that Gupta's home fills up and everyone around is forced to flee. “Everyone's entire house gets submerged. Last year, all of Delhi was flooded, and all our belongings were destroyed. We were lucky just to survive,” she said.

Gupta pointed to a cracked wall in her home that half-collapsed during last year’s rainfall and said her jhuggi was no longer safe to live in. “The entire wall broke and fell after it rained. Tell me, how are we supposed to live here?” The walls are damp and cracked with only temporary plastic sheets holding them together. Exposed electricity wires run dangerously across the waterlogged homes in the area.

She said her 75-year-old father, once a roadside vendor, is seriously ill. “The doctor asked for an ultrasound from outside [the hospital], but it’s too expensive. My only brother has already died. The government doesn’t care about us,” she said. At the government dispensary, she said, they’re treated “like insects,” which forces them to seek costly private care. “Even then, they just say come back, wait, six months, a year and nothing improves.”

She said no party has helped despite having voted for all of them. “BJP, Kejriwal, Congress, we’ve tried everyone. They make promises before elections, but once they win, they forget the poor even exist,” she said. Still she clings to hope. “Modi ji said, where there’s a jhuggi, there will be a house. If he’s promised, I hope he keeps it.”

“Even in a single room with a bathroom, we’ll manage,” she said. “Just give us dignity.”

‘We’ve Paid, Houses Exist, Why Can’t We Live In Them?’

Just 6–7 km away is the Partap Camp at Nehru Nagar, another JJ cluster. Here, too, people have been waiting for their promised flats for over a decade. Women show their documents as proof of registration and payments made for flats under the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM).

They say they have been waiting for their turn to finally move into dignified living spaces after living in the hostile surroundings of the camp for decades. The site is dangerous for their children, they say, as they hope their children would get a better shot at life.

But patience at Partap Camp is running thin, turning into anger.

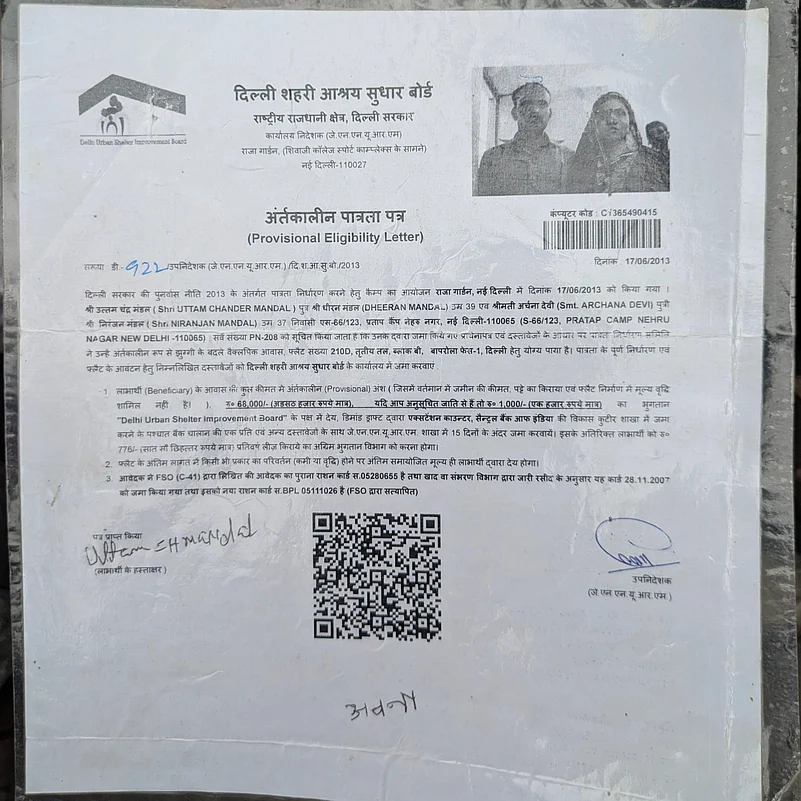

Archana Devi has lived in the camp since the late 2000s. Like the nearly 600 other residents, she’s spent over a decade waiting for relocation under the JNNURM. In 2013, she says, this basti was found eligible for relocation. About 300 families, including hers, paid the full amount required under the scheme, over ₹1 lakh each, on a tight deadline.

Archana borrowed from her relatives in her village to clear the payment in one go. “They told us if we didn’t pay at once, they would cut our names off the list.”

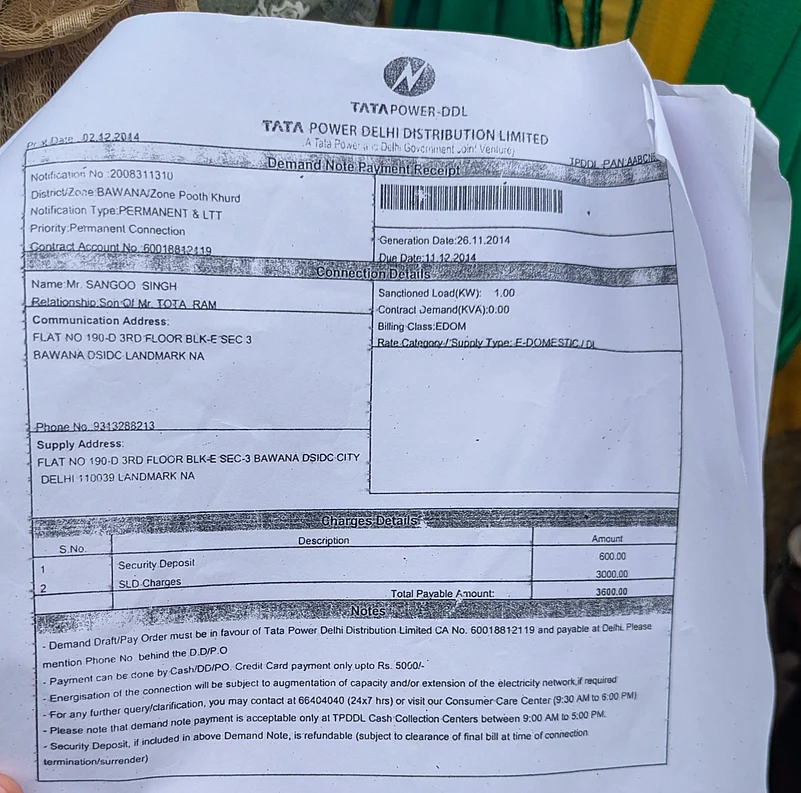

Around 50 others have even paid for electricity meters installed at the new flats that they have not spent a single day or night in, she says. “The meters are in our names; we’ve seen them with these eyes,” she says. The new flats, located in places like Baprola and Dwarka, remain locked and out of their reach.

“No one has been given possession papers. It’s been twelve years. They [officials and politicians] keep saying, another two months, four months, six months. How long will this go on for?” All the residents express surprise, even shock, that the flats meant for them exist, they have even visited them, but moving into them has proved impossible. “We don’t care if they’re unfinished. We’ll live in them the way they are. Just give us something,” said Archana.

“My message to Rekha ji [Delhi Chief Minister Rekha Gupta] is that she went to Dwarka, Baprola and Bawana. Flats have been approved for us in all three places. She should just send us there; no need to inspect anything. That’s all we say: we'll fix what is broken inside, just give us water and electricity connections,” says Archana.

What frustrates residents the most is the administrative runaround they're made to face. “The DDA says talk to L&DO, the Land and Development Office says talk to Delhi sarkar. Delhi sarkar says the flats haven’t been handed over by Delhi Development Authority. One throws the ball to the other,” said Archana. With the BJP in power as a three-engine government, at the Centre, in the State, and the MCD, she asks, “So why is nothing happening?” A woman sitting beside her mutters, “Over-engine ho gaya hai ab.” Devi laughs for a second, then quickly returns to serious.

In between their puns, one might forget basic survival is at stake. There’s no clean water connection inside the basti and no toilets. “We buy water cans every two days. Our daughters have to go all the way to the main road at night to relieve themselves; they are not safe.”

She doesn’t want subsidies or payouts, not even the promised financial assistance scheme launched with much fanfare. “I don’t want ₹2,500. I want bijli, paani and a dignified place to live. We’ll earn and eat,” Archana said.

In The Name Of Rehabilitation

There are 675 recognised JJ clusters in Delhi, as per a list maintained by the Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board (DUSIB). These have come up on land owned by multiple agencies, including the Indian Railways, the DDA, the L&DO, the Municipal Corporation of Delhi, the Central Public Works Department, New Delhi Municipal Council and others. Some bastis are decades old and the only home known to thousands.

The Indian Institute for Human Settlements (IIHS), in its 2020 report, Isn’t There Enough Land? Spatial Assessments of ‘Slums’ in New Delhi, takes apart the popular idea that JJ clusters have swallowed up large chunks of the city.

Drawing on field checks of the 675 plus 82 sites listed by the Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board, GPS mapping and Master Plan data, the researchers found that all JJ clusters together cover just 6.92–8.44 sq km, about 0.5–0.6% of Delhi’s total land, and 2.7–3.4% of land zoned residential.

Yet this sliver of land is home to 11–15 per cent, and perhaps as much as 30 per cent, of the city’s people. For IIHS, this is less a story of “encroachment” than of what it calls a “deep structural failure” of planning, decades in which “adequate land has never been made available for low-income residents,” leaving informal settlements as the only viable, affordable option for many.

The report calls for recognising existing settlements, reserving land for Affordable Housing Zones, and prioritising in-situ upgrades over mass evictions.

A separate list of 'Additional JJ Bastis' records more settlements not counted in the original list, often smaller clusters or those on forest, PWD, and gram sabha land. The combined list shows how crucial informal housing is to the city's immigrants, who make up its working class.

According to a report in The Times of India, the Urban Development Department has asked DUSIB to provide details of 82 slum clusters that have 'disappeared' from the official record. Though the list of 82 was briefly posted on DUSIB’s website, it was later removed, making its provenance uncertain.

Now, the Urban Development Department is demanding to see the complete file and records of surveys of these 82 clusters.

While DUSIB is responsible for rehabilitation of people living on slum clusters located on Delhi government land, DDA handles slums on Union government land. Most JJ residents are informal workers who must live near the colonies where they work, and include drivers, house help, sanitation staff and vendors.

The Delhi Slum & JJ Rehabilitation and Relocation Policy, 2015, approved in April 2016, deals with the lack of secure housing for the urban poor. Its core principle is in-situ rehabilitation, meaning jhuggi residents must be given permanent flats at the same site or within a five-km radius. Relocation is allowed under fairly broad circumstances, though, such as when the land is needed for an urgent public project, a court orders it to be removed or relocated, or the basti lies on a road, railway, park or safety zone.

To be eligible, a basti must have existed before 1 January 2006 and a jhuggi before 1 January 2015. A basti stands for a whole colony, whereas a jhuggi refers to a single dwelling place. The resident seeking eligibility for relocation or rehabilitation must appear in a survey conducted by the DUSIB, hold a voter ID card issued between 2012 and 2015, possess at least one of 12 identification documents and must not own a house in Delhi. Any jhuggi built after 1 January 2015 is not covered under the policy.

Each family must pay ₹1.12 lakh for a 25 sq m flat plus ₹30,000 for five years of maintenance. The housing is not free. That is why the residents of both camps Outlook visited said they paid up to ₹1.42 lakh or thereabouts for their own homes.

The Draft Master Plan for Delhi–2041, known as MPD-2041 was prepared by DDA and published in 2021, intending to guide Delhi’s development for the next 20 years. It projects a population of 29.1 million (2.9 crore) by 2041 and stresses the need for inclusive, affordable and climate-responsive housing.

MPD–2041 supports in-situ rehabilitation of informal settlements and encourages planned redevelopment of unplanned areas. It promotes rental housing, worker accommodation, hostels and dormitories, especially near mass transit corridors like the Delhi Metro. The plan recommends land pooling, public-private partnerships, and mixed-use development to integrate low-income housing into the city's fabric.

The plan was approved by DDA on 28 February 2023 and sent to the Union Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs on 13 April 2023. As of August 2025, it is still awaiting central notification, stalling implementation, and dashing hopes for a dignified home at Partap Camp and Shaheed Arjun Das Camp.

Even being on DUSIB’s list of recognised JJ clusters, the government of Delhi has demolished several bastis. On June 1, the Madrasi Camp at Jangpura, long-standing home to around 370 families, was cleared under a Delhi High Court order linked to cleaning the Barapullah drain. It featured in the official list of 675. In late May, over 300 jhuggis at the Bhoomiheen Camp in Govindpuri were demolished after the High Court dismissed petitions from households who did not feature on the official survey.

From late August to early September 2024, parts of Janata Jeevan Camp in Okhla (serial nos. 371, 378, 379) were demolished by the MCD despite pending court proceedings, displacing hundreds included in the DUSIB list.

A City Built By The Poor, Taken From Them

Karuvaki Mohanty, a lawyer with iProbono India, which advances housing justice, speaking to Outlook said that residents of Shaheed Arjun Das Camp and Partap Camp have followed every requirement under the rehabilitation policy.

“They’ve been surveyed, found eligible and paid the amount they were supposed to. Still nothing has moved,” Mohanty said. Despite the policy being in their favour, demolitions continue, often without notice.

“Sometimes there is no notice at all. Sometimes it’s just verbal, which we can’t even show in court. And if there’s no written threat, the court says, where is the notice?” Even bastis listed in DUSIB’s 2019 list of 675 JJ clusters are not spared.

She added that the promise of in-situ rehabilitation is not being implemented anywhere in Delhi. “Forget five kilometres, people are being pushed 30 kilometres away. They’re agreeing to [be moved to northwest Delhi's] Savda Ghevra, only because they’re desperate. When they shouldn’t even be sent so far, as they’ll lose everything.”

In September 2024, residents of Madrasi Camp in Jangpura, notified as JJ cluster under the DUSIB Act, were served a sudden demolition notice by the PWD, sparking urgent legal action. Though the cluster is legally protected under the DUSIB Policy, 2015 and the NCT of Delhi (Special Provisions) Act, 2011, authorities simply cited a prior court order concerning encroachments along the Barapullah to snatch away their only home.

Legal experts say the demolition was done without any rehabilitation plan, pre-demolition survey or meaningful consultation, all of which are mandatory under binding precedents like Sudama Singh v. Government of Delhi (no eviction without survey, engagement with those eligible for rehabilitation), reiterated in the Ajay Maken v. Union of India case. The Madrasi Camp case is currently before the Delhi High Court.

Advocate Talha Abdul Rehman, the lawyer for the Madrasi Camp residents, told Outlook that Delhi’s governance model has been set up so that real power doesn’t rest with the elected government. And says that instead, it lies with the DDA and the Lieutenant Governor, “neither of whom face electoral accountability.” According to him, this isn’t just a legal loophole but a “constitutional anomaly” that has the effect of silencing voters. “It places their lives at the mercy of unelected bureaucrats.”

The problem at the core of it all, he said, is structural: the poor are treated as disposable, allowed to build the city but pushed aside for its 'development'. “They’re not just dismissed as vote banks but vilified as obstacles to development,” Rehman said, adding, "What's happening is erasure masquerading as planning."

The residents of Partap Camp and Shaheed Arjun Das Camp have little to do with planning or governance. All they want is a new home, one that promises them better health and, most of all, dignity, especially after they have paid for it.