Majnu Ka Tila, a Tibetan settlement in North Delhi, is often referred to as the ‘Mini Tibet’ of the capital. It was established in the 1960s, after Tibetan refugees arrived in India following the Chinese occupation of Tibet. The area is marked by restaurants, shops, prayer flags and other symbols of Tibetan identity that reflect the community’s roots.

A short distance from Majnu Ka Tila is another refugee settlement, much less famous and home to Hindu families, mostly farmers, who came to India from Sindh, Pakistan, in 2013, citing religious persecution. Around 800 people currently live in the camp, and at least 300 of them have been granted Indian citizenship, whereas others continue to face delays and rejections in their applications.

Many say that renewing long-term visas every year is both costly and difficult, and that despite having lived in India for over a decade, they still lack permanent legal status. The refugees said the area was once a jungle, and that they cleared it themselves to make it liveable for their families and future generations.

However, the Delhi Development Authority (DDA) has now issued a demolition notice, throwing their lives into fresh uncertainty. The agency states that it’s acting under environmental regulations and a Delhi High Court order, which upheld plans to clear all settlements from the Yamuna floodplain, the land on which this camp stands. The court ruled that even though the families have lived here for over a decade, they have no legal right to stay. Environmental law, it said, cannot be set aside, not even on humanitarian grounds.

'We’ll Die Here, But We Won’t Leave.'

The entrance to the camp appears just after the Majnu Ka Tila gurudwara. Along the roadside, vendors, mostly from the settlement, sell mobile phone accessories alongside small general stores. A narrow path after these stalls leads into the camp, where the homes are made from tin sheets, wood and bricks.

Each house is marked with a jhuggi number allotted by the government, says Ganga, a resident of the camp.

“This is one house with one washroom and one kitchen, shared by at least four different families. There are twelve of us living here, and this is how compactly everyone lives,” Ganga says.

Ganga introduced me to her mother-in-law, Shanti Kumari, who has been living at the camp since it started to take shape in 2013.

“Where will we go?” asked Kumari. “Pakistan was our birthplace, but we came to India hoping for safety and dignity. We can’t go back. The government let us settle here, and it took years to turn our shelters into pucca homes. Now they want to evict us, what kind of protection is that?”

She said they had done everything possible to get citizenship, trusting that India would give them a fair chance. “We don’t even have a gaon [village] here. Others can return to their villages in Bihar or UP when things go wrong. We have nothing. This camp is our home.”

Asked if she would move if offered another place, she shook her head. “Where will they send us? Will there be a school like the one our kids go to? Hospitals? Roads? Safety?” She paused. “They’ll dump us in some khandar [deserted area]. We’re not going anywhere.”

Ganga, Kumari’s daughter-in-law, said the government might see their settlement as a stain on the city or a hurdle to development, but both sides had their reasons. “They’re right in their own way, and we are in ours,” she said. “But who decides which truth matters more?” For them, this place, despite its hardships, was still home. It held more value than gold. Somehow, they were surviving and even finding moments of happiness.

“Do you know gods live here?” cackled Pooja, Sukhnand Pradhan’s wife, a longtime resident. Her children were all named after Hindu deities, Laxmi, Ram, Krishna and Saraswati. It had taken blood, sweat and years to rebuild what was lost. What began as a makeshift cluster had slowly become homes with solid roofs. Electricity arrived only four years ago.

But when I brought up the eviction notice, the laughter faded, and her expression changed. “And now, just as we’re beginning to live a little,” she said, “they want to throw us out again.”

“Our children are safe here, and it makes us happy to see them go to school here and have a life. We’re not leaving, no matter what. Even if it means dying here,” she declared.

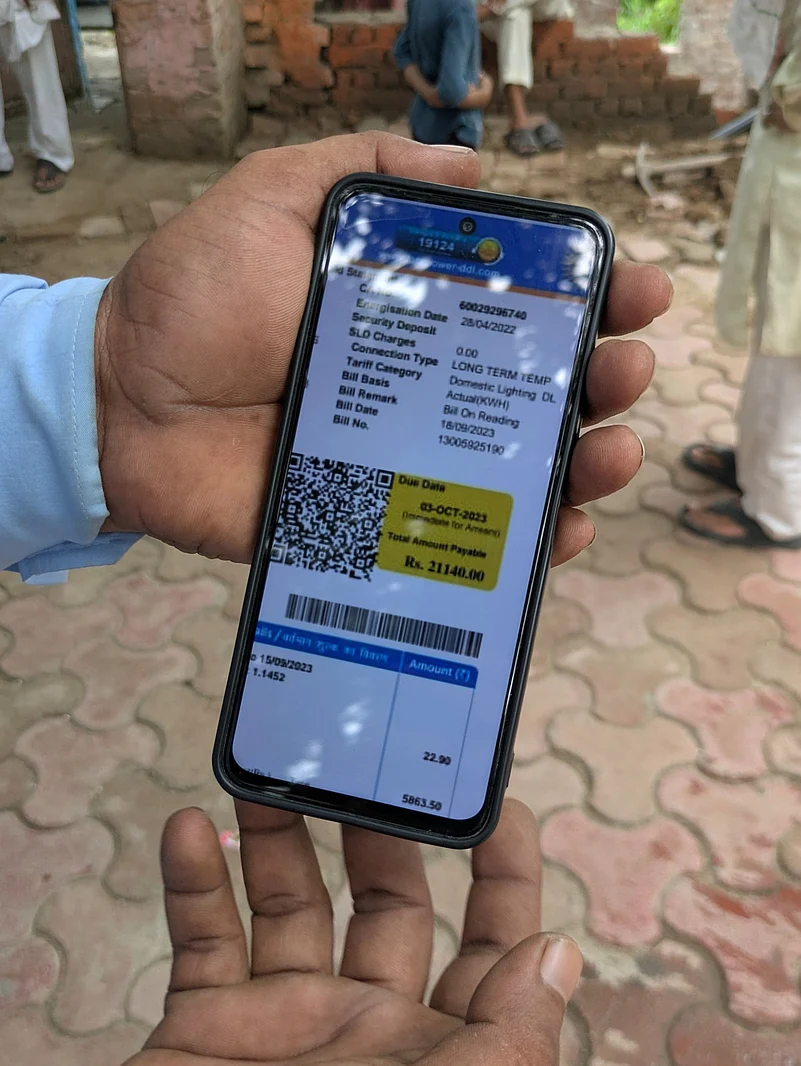

Basic services are available in the camp, though not always reliably. Drinking water is supplied through Delhi Jal Board tanks and electricity is accessed through installed meters. However, residents say that the bills are often too high to manage.

All residents echoed how electricity bills were causing them the most distress. The high charges added to their already difficult lives, where most of the men rely on pulling rickshaws, doing daily-wage work, or running small vends.

“It’s extremely difficult. We don’t even get the 200-unit free incentive that the Delhi government gives to others,” said one resident, back at Majnu Ka Tila. “We get bills of 15,000 to 20,000 rupees per house, even though we only use fans, lights and coolers. How's this fair?"

'Not Even Allowed to Struggle': A Refugee Teacher’s Plea

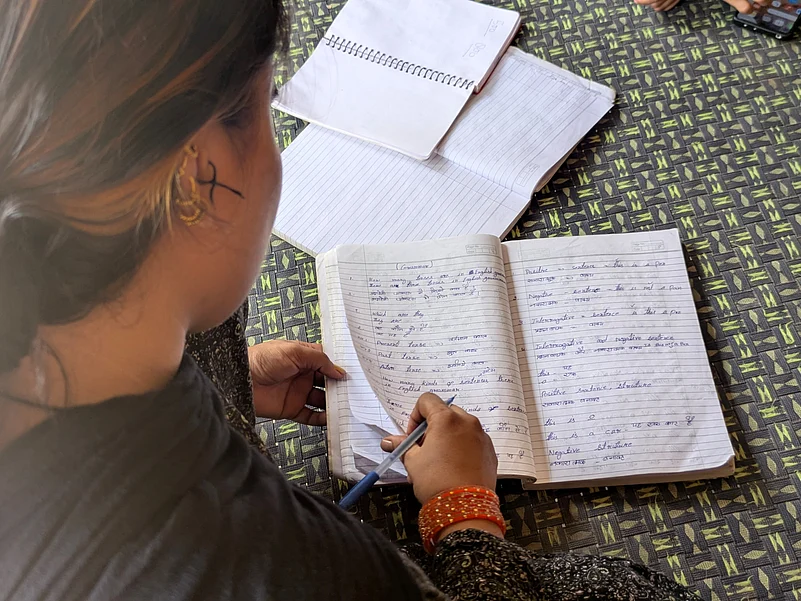

Ram, 28, lives in the Signature Bridge camp and travels the roughly 2 km to Majnu Ka Tila every day to teach refugee children Hindi and English. He arrived from Sindh, Pakistan, just three months ago. In Pakistan, he had run three private coaching centres named Bright Future, where he taught English grammar to schoolchildren. Many of his former students, he says, now have good jobs. Here in Delhi, he earns ₹300–400 a day by teaching outside the camp but still finds it difficult to meet basic needs.

He had come to India with a vision, not to escape, but to rebuild. “A dream is not what you see when you sleep,” he said. “It’s what keeps you from sleeping.” But the reality he encountered was one of closed doors and deep frustration. “People don’t even let us struggle,” he said.

What moved him most, he said, was the condition of the children in the camp. Some of them, already ten or twelve years old, were unable to get admission to schools because they lacked Aadhaar or PAN cards. Ram feared that without education or recognition, they would be forced into a cycle of poverty. “They’ll end up selling kachori or pakoras on the street,” he said, not because of a lack of ability, but because of bureaucratic cruelty.

His own efforts to legalise his stay had repeatedly failed. Despite holding Intermediate and Matric certificates from Matyari Degree College in Sindh, and despite proving that he is a Hindu refugee, his Long-Term Visa application was cancelled multiple times. Each time, he was told to reapply. “How can someone like me, with no income, keep applying again and again?” he asked.

Ram believes there is a double standard. He said that foreigners from places like Turkey, China or Australia often live and work freely in Delhi, yet Pakistani Hindus like him are questioned at every step. “They ask us, who are you, what did you do back there?” He said that even after showing documents proving both his religion and education, officials still dismissed his case.

He insisted he wasn't asking for charity, only the bare minimum to survive with dignity: “We don’t want money. Just give us Aadhaar cards and citizenship. We’ll earn and live on our own.” The psychological weight of uncertainty is compounded by what he sees as a lack of empathy. “Imagine an Indian leaving their home, their job, their family and going somewhere completely unknown. That’s what we’ve done.”

For him, the choice was never between poverty and comfort; it was between dignity and extinction. “We built a life in Pakistan. We left everything behind. Now we’re building again. But if they take this land too, how will we survive?”

Visas, Evictions and Unequal Neighbours

The DDA issued a public notice on 14 July 2025, asking residents of the refugee settlement near Majnu Ka Tila to vacate the area by the next day. The notice cites a 29 January 2024 directive by the National Green Tribunal, which instructed DDA to clear all encroachments from the Yamuna floodplain under its jurisdiction. It also references a Delhi High Court judgement that ruled in DDA’s favour.

A demolition drive was scheduled for 15 and 16 July, targeting the DDA land south of the Gurudwara at Majnu Ka Tila, along the Yamuna’s western bank. The notice warned residents that if they failed to vacate by 14 July, they would be held personally responsible for any loss or damage caused during the demolition.

Many pointed to the nearby Tibetan refugee settlement, expressing frustration at how those refugees seemed to have built far better lives. They said the government had been more cooperative with them, allowing them to run restaurants, access work opportunities and send their children to good schools.

Krishn Bagli, a farmer from Sindh now living in the camp, said it felt like his community had been forgotten. “How come the Tibetans have a better life than us? They get all the facilities,” he said.

Bagli recalled how the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government had settled them in this area, and now, just as their lives were beginning to stabilise, they were being asked to leave. “If they remove us from here, it’s unjust,” he said, adding that many residents who had received Indian citizenship had voted for the "Rekha sarkar", referring to Delhi's first BJP Chief Minister in 26 years, Rekha Gupta, who took charge after elections this year.

He admitted that city life had never suited them. “We are farmers from Pakistan. Honestly, we don’t even like it in the city,” he said. “If the government gives us a safe haven where we can peacefully farm and send our children to school, that will be more than enough. But if that’s not possible, then we just request them to let us stay here. We’re not harming anybody. We earn little, eat little and somehow survive.”

Amarlal, another resident of the camp, said it was unfair for the government to suddenly raise objections now, after letting them live here quietly for so many years.

The government tells them to renew their Pakistani passports, even though many question why that’s needed after a decade in exile. “Even if we somehow collect the money and get the passports renewed, what difference does it make? We’re still stuck in the same place," Amarlal said.

What they really want, he said, is simple; citizenship, safety, and the right to live in peace.

No Home, No Ruling, No Relief: What the Court Said

The legal case around the Pakistani Hindu refugee settlement near Majnu Ka Tila began early last year with a petition filed in the Delhi High Court by Ravi Ranjan Singh. He asked the court to stop the DDA from evicting around 800 residents. He argued that the demolition should not take place until the government gave them another place to live. He also referred to the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), 2019, which was meant to support persecuted minorities from Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh.

On 12 March 2024, the court gave the residents temporary relief. It stopped the DDA from taking any action against the camp for the time being. It also took note that the community had been living there for several years, had access to basic facilities like water and electricity, and that many of their children were studying in nearby government schools. The residents had been told to vacate by 6 March, just two days after receiving the notice.

Ravi Ranjan Singh also referred to a 2013 court order in the case of Nahar Singh v. Union of India, where the central government had said it would support Pakistani Hindu refugees. But the High Court said that the 2013 order only mentioned visa support. It had not promised permanent housing or land. So, the court ruled that the current residents had no legal right to demand alternate land.

One major issue in the case was the location of the camp. It lies in Zone ‘O’ of the Delhi Master Plan, marked as part of the Yamuna’s floodplain. Under orders from the NGT and the Supreme Court, no houses or buildings are allowed on this land. The DDA said it was following these rules and had to clear all encroachments, whether shops, homes or any other structures. The court agreed and said humanitarian concerns could not override environmental laws.

On 30 May 2025, the court also noted that even after several hearings, different departments of the government had failed to come up with any solution. It described the situation as “a classic case of bureaucratic buck-passing”. It pointed out that neither the Ministry of Home Affairs nor the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs had proposed any relocation plan for the residents.

The Ministry of Home Affairs told the court that it had no role in relocation. Its responsibility, it said, was only to process citizenship applications under the CAA, 2019. It added that refugees who are eligible can apply for Indian citizenship through the official portal.

The court also looked at the Delhi Slum and JJ Rehabilitation and Relocation Policy of 2015. This policy applies only to Indian citizens, which means most of the residents of the camp are ineligible. The court noted that even citizens cannot be guaranteed land in areas like the Yamuna floodplain, where construction is banned.

In the final order passed on 30 May 2025, the petition was dismissed and the protection given earlier was removed. It said the court could not change environmental rules or create new policies. As a result, the residents now face the risk of eviction, with no confirmed plan for where they will go next.