Summary of this article

Imagined worlds revisit the bonds, and losses that shape lives.

Spaces reveal a fractured world, where belonging is often contested.

They become places where silenced stories and fragile hopes can still exist.

A story can take place in a space not confined to the present but unfolding in the future, the past and other worlds. What goes on in constructing these worlds? How does the architecture of an imagined building reflect politics, society and us? Is it premonition? Are dystopian spaces prophetic? Is it the urge to belong and negotiate with modernity, as in Malgudi? Or an escape into magic, like Macondo?

The spaces of fiction become social products, expressions of our worldviews, a strange map where memory mixes with everything to render a space not yet reachable, and yet a space which delivers us respite from our restlessness. The backdrop is a character in the narrative.

Home is a major theme of our times, as wars displace people and class divides widen. How do we speak of the nation state, fixed spaces and identity when censorship has become the order of the day? Talking is impossible today, and thus we return to the pen: writers, our allies.

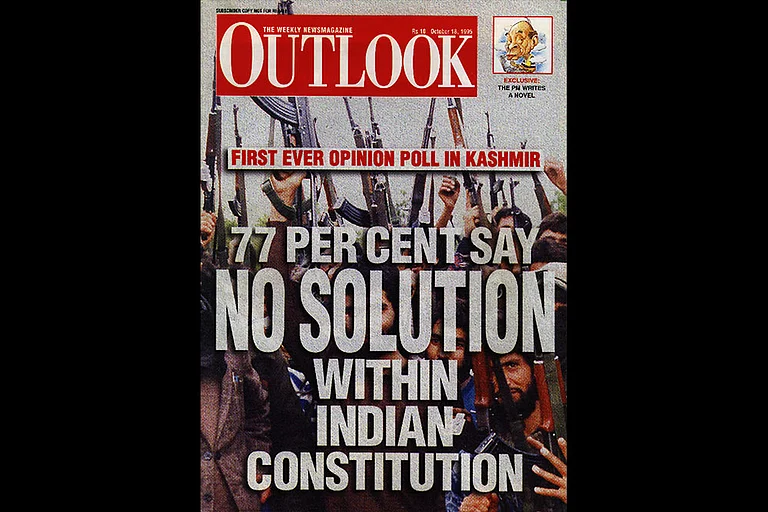

For this anniversary issue of Outlook, celebrating 30 years, we would like to dissect the urge and creation of imagined spaces as acts of transition, prophecy and resistance.

If only, I could go back to my 'elsewhere'

Vidya Ramamurthy

I was walking along the river admiring nature when I stumbled upon a group of women chatting and painting mud pots. Few others were beading beautiful wrist bands and necklaces. The sun was setting and I could smell kitchen fires.

One of the women asked me if I had lost my way. I nodded and asked her to guide me back to the nearest town. Another woman chimed in, "Why don't you eat something and then leave". She called out to a group of men who seemed to be busy with a community kitchen sort of a setup.

Few men were busy chopping vegetables, while others were engrossed, feverishly stirring pots of many sizes. The woman called out again, and a man came hurriedly with a bowl of steaming soup and freshly cooked vegetables.

I was quite curious to know how come the women folk were sitting, while the men were busy cooking. The woman seemed to have read my mind. She laughed and said, "It's a taboo for women to cook in our tribe".

I was now more curious to know what the womenfolk did. "So, you work all day and the men stay at home?", I asked. "Not at all", she replied.

"They cook, go out to the fields, work, come back, and again cook. They do everything, cook, clean, cut, work. We only make handicrafts".

If only, I could go back to my 'elsewhere'.

Our Own Elsewhere

I have been pondering lately, about the idea of an elsewhere. A space that exists slightly apart from the daily labour of being palatable, docile and alert. The idea of an “elsewhere” carries its own ache—a world apart from this one, with only a single lifetime to dream of it. Imagining a utopian reality while the world outside remains relentlessly unforgiving to many, can feel like a betrayal. Yet I realise it is also a form of quiet empowerment. Our world is fractured by wars, women and minorities are unsafe everywhere and governments brutally undercut dissent. In such a reality, an elsewhere becomes a necessary refuge—a place to survive another day and to hold the possibility of freedom, even if only for a moment.

In an attempt at conceiving an “elsewhere”, Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain’s Sultana’s Dream (1905) was the first place my mind drifted off to. Back in the day, it was the first short story in my limited vicinity and exposure that offered a world where women truly moved unapologetically. They were engineers, scientists, writers, rulers and most importantly, themselves. In imagining it, I found a quiet haven and I could linger there for hours, making up friends I had not yet met.

Many years later, I stumbled across an article about the Supershe Island in Finland and scrolled through the photographs. An entire island where only women are allowed—wandering the beach, laughing in the wind, truly unobserved by men. The language around the island within the article itself was cautionary, as though the absence of men needed justification. The comment sections were predictably filled with hate comments. Although, I have often wondered what it would feel like to inhabit that space for even a day. Can one truly be unburdened of a lifetime's worth of vigilance and violence? I truly don’t know how that would feel. Will I go mad? Maddeningly giddy? Perhaps.

For my younger self, “elsewheres” manifested in wistful online spaces too. It was where I first encountered platforms like Tumblr and Pinterest where I continue to return to. It exposed me to so many interesting accounts filled with women sharing art, pictures, fanfictions, academic notes and their frustrations. I also think about “GirlsGoGames”, a cutesy gaming website that reminds me of those late 2000s summer vacations, cold lemonade and not a single care in the world. Back then, Instagram too, was simply a space to document photos. It’s almost absurd to say one yearns for the internet of yesteryear, but over a decade later, it has become an unrecognisable, unwelcome place. I feel the pull of a younger self—the girl who believed she could be anything. I remember how small the world felt when I was nine, how limitless imagination could seem.

Thinking of these spaces brings back memories of girlhood: of mothers, sisters and daughters who never had the chance to be girls themselves. A Sultana’s Dream or a Supershe Island remains my compass in the absence of certainty—a place I can revisit perpetually. In these “elsewheres”, I imagine women reclaiming those lost years, where childhood and adulthood now coexist—first in imagination, then perhaps in the real world, if such spaces are cherished and nurtured.

I wonder if we can ever carry this “elsewhere” into streets, homes, offices and classrooms, or if it will remain forever in imagination, in censored writing, like a radical and tender secret? I carry my invented elsewhere like a secret warmth. It is selfish, yes, to want a space untouched by the constant demands of survival and expectation but in imagining it, I protect the self I have always needed to protect. And in that reclamation, perhaps, we find a courage soft enough to keep dreaming and steady enough to keep living.

No Weird Fishes for Me

Anupam Sai Bollaboina

Last November, I visited the coastal city of Vizag for the first time. I imagined a place with a vast coastline, humid climate and delicious sea food. While I was looking forward for the trip, I came across a rumour which said they were building a data center in Vizag.

My fantasy of eating Prawn Fry shattered as I was now imagining the waters getting polluted.

Once I reached Vizag, I started noticing that the city itself is sponsored by a massive tech conglomerate as the logo appeared on every billboard where Vizag (VizaG) was written.

I sat for dinner with a local on Law College road. While eating some Fried Fish and Calamari, he told me that this place is very close to the IT sector. I asked him if this is where they are building the data center. “Yes”, he said proudly and I couldn’t help myself but ask about the water pollution. He shrugged and said, “the waste always gets dumped in the middle of the sea, there are pipelines.” It made me wonder when I come back to Vizag the next time will I even be eating sea food.

Later the same month, a friend of mine texted me saying he made a meal plan on a popularly used AI chatbot. It recommended him to eat more fish to gain Omega-3s. Ironic as it was, I asked if its the very fish the chatbot is poisoning?

Imagination As Resistance

Karl Marx, in his restless attempt to imagine a world cleansed of exploitation and alienation, never drifted away from the soil of reality. He built his thought on the facts of the world as they exist, yet he insisted that what ultimately sets humans apart in this vast universe is imagination. It is this quiet, anticipatory power that allows human beings to dream a form before it comes into being.His comparison of the spider and the human remains one of the most enduring passages in Capital. A spider weaves with astonishing skill; a bee constructs honeycombs of near-perfect geometry, often surpassing human craftsmanship. And yet, Marx reminds us, even the worst architect differs from the most gifted bee in one decisive way: the human being first raises the structure in the mind before setting it down in the world.Labour, for Marx, is thus not mere exertion of muscle or instinct. It is an act of foresight, a conversation between imagination and matter, where the future is briefly rehearsed in thought before being fixed in brick, steel, or stone.So be it. It may well be that the capacity to imagine is what makes the human being free.

Imagination loosens the grip of necessity; it allows one to step beyond what merely is and glimpse what could be. In art and literature, in the shaping of ideas about society itself, imagination becomes an act of quiet defiance.To imagine is to refuse the tyranny of the given. It is to insist that the present is not final, that history is unfinished. In this sense, freedom does not begin in the streets or in institutions alone, but in the mind, where another world is first conceived before it is struggled for, written into being, or built by collective hands.By refusing tyranny and subjugation, countless people across the world have been imprisoned. History is crowded with bodies behind bars for the simple crime of saying no. Yet the understanding of tyranny—and the resolve to resist it—remains the essential prerequisite for imagining another possible world, one founded on love, compassion, and free of exploitation and alienation.Perhaps this is why certain extraordinary souls, though physically confined, continue to taste freedom. Behind prison walls, imagination becomes an inner horizon that no jailer can seal. It is sustained by a deep comprehension of the world as it is, and a stubborn faith in what it could become. Nelson Mandela may well have survived decades of incarceration through such imaginative endurance. Even Winston Smith, in the fleeting moments of rebellion in Orwell’s 1984, clung to this fragile freedom.So too do thousands of political prisoners languish in jails across the world today. Whether in cells or in clandestine lives, it is the imagination of another world that sustains them. Bars may confine the body, but the idea of freedom—once imagined and understood—refuses to be imprisoned.So where does one take refuge when the heat of the present material world becomes suffocating? There are many worlds on offer, many shelters of thought and belief that one can cling to. The worlds I have invoked above point toward the one I wish to inhabit. Perhaps many of us do—unless we fully surrender to the brutal logic of survival of the fittest.Yet I remain a pragmatist. I know that imagining a world founded on love, compassion, and freedom from exploitation—one that thousands across the globe strive for—comes at a cost. It unsettles. It invites punishment. It can ‘ruin’ lives. And so, faced with this ‘knowledge’, I often choose the wretched certainty of a compromised world over the tumult of a material life lived in open resistance. I accept a topsy-turvy order, not because it is just, but because it is survivable.Imagination, in my political understanding, is never neutral; it invariably challenges the status quo. I, too, imagine. But unlike the hundreds of thousands who imagine and then resist, I recognise that my imagination is crippled by an unwillingness—or perhaps an inability—to resist. This is the contradiction I live with.And so I long for a moment, or a condition, in which I possess the wherewithal to complete the journey—to allow imagination to mature into resistance, to let thought acquire courage, and to step beyond mere survival into the risky terrain of freedom.

A Departure: Away From The Gaze

The idea of an elsewhere inherently suggests fantasy, a lush departure. Reimagination is coded in. When we think of it, we’re whisked to our best hopes, a life of endless possibility. Whether elsewhere is a retreat or a complete radical break can be argued. It may both be a refuge and reinvention. I look at elsewhere closely tied to my identity, particularly, my queerness. It’s a delicate consideration that constantly resigns the self to denial and yearning. To accept yourself is a long journey, fraught with confusion and loathing and shame.

Even besides persecution and judgement, queerness is put on a tight rope. Beyond the coming-out trajectory, we confront families, ecosystems and institutions driven to erase and mute out voices. The system is designed to render uniform identity. Then there’s queerness being hijacked by mainstream cultural expectation. There’s a dangerous co-opting under the excuse of inclusivity that rubs out queer specificities. Suddenly, you find yourself cornered. Unless your existence is actively negated, you’re supposed to look, behave, desire a certain way. The acceptance and celebration move in a neat, tight grid. Precise coordinates are laid out wherein you arrange and mold personality. I’m always hyper-conscious of the performance sought from queerness, the space between it being harmless and genial and uncomfortable. Just the individual level itself gets heightened. You’re acutely made aware of your precarity. Getting to exist beyond almost feels like a privilege, no matter what era it is.

When I dream of an elsewhere, it’s where I can just be, away from a framing, objectifying gaze. This purview instantly implies victimhood and power differentials. In my elsewhere, sexuality wouldn’t be the primary affiliate but couch subjectivity. The two would be conjoined. The trouble with queerness is it’s seen as an add-on, almost creating a remove between the self and the other. In its worst, it can be a prison, even in the absence of hostility or prejudice. Conditioning tricks you into folding within a box. You already internalize difference, perceive yourself as set apart. It’s this strange dislocated space of functioning. You're wired to thinking within the scope of what's at stake. Happiness feels like a mercy. My elsewhere doesn’t let this creep in. The place allows relationships and friendships to view queerness as expansive, not to flinch at. There’s generosity, being welcomed without one cannibalizing the other. When queerness thrives in multiplicity, this elsewhere promises beauty and joy. I wish for sexualities to be embraced, crisscrossing caste, religion, social locations. When we move beyond judgement and court experimentation, freedom can be found. My elsewhere will be kinder to queerness, liberate it from dogmatic presentation, pull it towards glorious diversity. All across various ends of the spectrum would co-exist and learn from one another. This shared language will rescue us.

Finding My Elsewhere In The Mosh Pits

The night I remember most clearly smelled like sweat, dust, and cheap beer, somewhere in the dark lanes of Mumbai. The venue was loud before the music even started—vendors shouting, bikes passing, bass lines leaking through concrete walls. When the first guitar finally let loose, it felt less like sound and more like a physical force, pushing against my chest and rearranging my breathing. In the mosh pit, bodies collided without apology, strangers held each other upright, and for a few hours the city outside dissolved. That space was dense, chaotic, ecstatic and felt like an elsewhere, a place I didn’t have to explain myself.

Heavy metal concerts in Mumbai always carry that sense of defiance. The crowd knows it is claiming something temporary and fragile. You headbang not just to the rhythm but to prove that this music belongs here too, that rage and release can exist alongside traffic jams, monsoons and the hustling spirit of Mumbai. I remember closing my eyes, feeling the drums echo through the floor, and thinking that this was the closest I ever came to silence, because everything unnecessary fell away.

Sometimes my mind drifts further back, to 1991, to Metallica playing in Moscow before 1.5 million people. I wasn’t there, but the footage lives in my imagination like a memory borrowed from another life. A sea of humanity stretching beyond sight, military helicopters overhead, amplifiers roaring louder than history. I imagine what it must have felt like: metal not as subculture, but as an earthquake, a moment when the music cracked open a system and let something wild spill out.

That imagined Moscow crowd and my very real Mumbai mosh pit merge into one feeling. Metal music created a temporary homeland, loud, bruised, honest, where anger turns communal and joy is earned through distortion. That is the elsewhere I return to in my head, whenever the world feels too orderly, too small.

A Land With No Lands

There is a world I would like to see—one that John Lennon sings of, a land with no borders. This imagined world has returned to me again and again, taking different forms each time.

“Imagine there’s no countries,” Lennon sings. And as he said, what he imagined “isn't that hard to do“, for there was a time when borders did not exist as they do today. Benedict Anderson famously described the nation as an “imagined community”, a human-made construct. An environmentalist friend once said something that stayed with me: animals and nature do not recognise borders.

So I find myself wondering—who gets to draw lines across the soil of our shared world and decide which side belongs to whom? Why do we continue to live within borders when it is these very definitions of countries and ideologies that have divided us and fuelled conflict? Is the world not wide enough for all of us?

I imagine a nomadic world, one borrowed from the animal kingdom. We often argue that humans are too different to exist under a single umbrella, yet animals, diverse in every possible way, are grouped under a single term and coexist. They wander freely; prey and predator can drink from the same stream. We, on the other hand, build dams, draft policies, and sign treaties that separate even our water from our fellow humans.

We have become both hunter and hunted—depending on which side of which border we stand.

This idea resurfaced in an unexpected place for me: a light-hearted children’s anime, Spy×Family. In one scene, the child protagonist visits a zoo, drawn in by a banner advertising the world’s most dangerous animal. Inside the cage, there is no beast—only a mirror, reflecting the humans who came to look.

A sign reads:

“This is the cage of Homo sapiens, the most widely distributed animal on Earth. Extremely territorial, they never cease to engage in conflict within and between their packs. An aggressive and dangerous species.”

Man—the most dangerous animal.

If it is our imagined borders and imagined communities that divide us, then I imagine something else entirely: a land with no lands at all.

I Want A Rage Room In My Mother's Home

There was a time when I felt proud of inheriting my mother’s patience. She was widowed at 24, left to raise two daughters and the responsibility of caring for an ageing mother-in-law. After my father passed away, she took up a clerical job and learnt how to survive on routine, restraint and silence. She raised two daughters on her own, gave them the best education she could afford, and held an entire household together without ever appearing overwhelmed. Calm became her architecture of survival.

That belief collapsed the day I lost my patience at work.

Something went wrong and it consumed me. I stopped speaking to anyone. I snapped at those who tried to comfort me. My anger spilled without shape or discipline. And in that moment, I realised that I do not carry my mother’s patience. What I carry instead is an impatience with silence, an inability to stay contained.

What troubles me most is that I have never seen her enraged. She lived through a lifetime of loss. Married at 19, widowed young, never remarried; she endured things I do not wish to speak of and spent her twenties and thirties tending to other people’s needs. There was grief, sadness, guilt but never rage. Rage had no room in the house she built.

But I want to see her furious - breaking-things furious. I want her anger to occupy space, to disrupt the order she so carefully maintained. Not because anger is going to fix anything but because it is honest.

My mother’s home was built on patience and endurance; its walls reinforced by silence. It was a space designed to be livable, not loud. I hope that one day a rage room actually finds its way in her home.

Maybe, at the time, that silence was a necessity. Perhaps restraint was the only way survival was possible. But silence also travels through generations. It becomes inherited architecture. I don’t want my mother’s patience. I want her to have my rage.

Khayali Pulao: My Elsewhere

There is a phrase people use casually.

“Bas khayali pulao paka rahi ho.”

It is usually said with a half-smile, a gentle warning that you are dreaming too much, thinking too far ahead, imagining things that may never happen. I have heard it often. And I have always taken it seriously.

Khayali pulao is my elsewhere.

It is the place I go to when reality feels either too loud or too narrow. It is not a grand escape, and it does not promise success or certainty. It simply gives me space. Space to imagine without being interrupted, corrected, or rushed.

I have been cooking khayali pulao for as long as I can remember.

As a child, I would sit quietly in rooms full of adults and build entire scenes in my head. Conversations that could have happened but did not. Endings that felt kinder or more complete than the ones I witnessed. I was not unhappy. I was occupied. Busy somewhere else.

At family gatherings, while others argued over politics or passed judgment on relatives who were not present, I would drift. My eyes followed ceiling fans, window grills, and patterns on curtains. In my head, I was rewriting the room, making it softer, slower, more forgiving. No one noticed. Or maybe they did and chose not to say anything.

For me, khayali pulao has never been escapism. It has always been a rehearsal.

I imagine things not because I dislike my life, but because imagining helps me understand it better. When I replay moments in my head, I notice details I missed the first time. A hesitation before a reply. A glance that lingered a second too long. A silence that carried more meaning than words.

Over time, my elsewhere became more specific. It began to look like empty spaces. Half-lit rooms. Streets just after rain. Film sets before actors arrive. Places where something has happened or is about to happen, but nothing is demanded of you yet. There is deep comfort in that in-between.

Real life expects clarity. Decisions. Reactions. Opinions. You are supposed to know where you stand, how you feel, and what you want. Khayali pulao does not rush you. It allows you to stay confused for a while. In my imagined space, I sit with unfinished thoughts. I do not force answers. I let them arrive when they are ready.

Some people plan their future in spreadsheets. I plan mine in fragments. Scenes. Moods. A feeling I want to hold on to, even if I do not yet know what to call it.

There are days when my khayali pulao is romantic. I imagine conversations going better than they did. Words spoken at the right time. People understand each other without too much explanation. On other days, it is painfully practical. I imagine worst-case scenarios and prepare myself emotionally, not to panic, but to soften the blow if it comes.

This elsewhere has protected me more than once. When things did not work out the way I hoped, I had already visited that version of disappointment in my head. I knew its shape. I knew how it felt. When it arrived in real life, it did not destroy me.

Khayali pulao is also where my relationship with art lives. Long before I held a camera or opened a diary to write, I was collecting moments in my head. Not dramatic ones, but small, ordinary scenes. Someone is waiting too long at a bus stop. A woman standing at a kitchen sink, lost in thought. A man rehearsing a phone call he never makes. Those images stayed with me, quietly shaping how I see the world.

I realised early on that I am drawn less to spectacle and more to stillness. To what happens just before and just after something important. That comes directly from elsewhere. In khayali pulao, there is no pressure to entertain. Things can be quiet. Even boring. Especially boring. Boredom is where honesty sneaks in.

In real life, I often feel slightly delayed, like the world is running a few seconds ahead of me. By the time I am ready to speak, the conversation has moved on. By the time I process how I feel, the moment has passed. Earlier, this frustrated me. Now, I accept it.

My elsewhere gives me something others might not notice immediately. Patience. Depth. The ability to sit with discomfort without needing to fix it. It teaches me to listen properly, without preparing a response in my head. It also teaches me restraint. Not every thought needs to be shared. Not every emotion needs an explanation. Some things grow better in silence.

People worry that imagining too much distances you from reality. I have found the opposite to be true. Imagining makes me more attentive when I return. I notice people more carefully. I sense when someone needs space instead of advice. My elsewhere sharpens my presence; it does not dull it.

Of course, there are moments when I overstay, when thinking replaces doing. When comfort turns into avoidance, those moments are real. I do not deny them. But even then, my elsewhere nudges me back. It reminds me that imagination without movement goes stale, like food left untouched for too long.

Everyone has an elsewhere. Some call it ambition. Some call it faith. Some bury it under routine. Mine is khayali pulao. A place where I test possibilities before I live them. Where stories begin without knowing how they will end.

The party, as they say, is elsewhere.

And for me, that elsewhere has always been enough.

I Defy And Resist The Erasure!

When I read Uruguayan writer and journalist Eduardo Galeano’s ‘Open Veins of Latin America’, for the first time, it was not merely a moving book difficult to keep aside, not only an imperialist history. It was defiance against human exploitation of all kinds. Galeano refused the erasure of memory.

He (Galeano) walked me through the individual and collective path of human memory. Human Memory is the fragile terrain where worlds are overturned, where joy, pain, suffering, longing, and conflicts coexist. It is where lives are constantly reshaped.

Although structures invade this terrain of memory with many weapons – not arms and nuclear bombs every time, but with carefully designed political projects that impact human lives, inviting more conflicts within. One tends to choose whether boycotting corporate companies complicit with genocide in Gaza can satisfy the self-conscience or sharing ‘All eyes on Rafah’ status will be seen as an act of transnational solidarity. And then there are conflicts about choices we make to survive. The constant race to survive and the survival of humanity is far more complex than ever.

This complexity pulls me back from dreaming Utopia or rather contributing to create one. Utopia-Eduardo Galeano’s Utopia. But beyond this pathway of reaching elsewhere; conflicts between what is happening outside and within often transpires to the erasure of memories.

In my memory log, key words like Starvation in Gaza, missiles on Ukraine, handcuffed Venezuelan president Nicolus Maduro, bail denied to Umar Khalid, massacres from Nazi Germany to Modi’s India and Trump's USA, human-made famines surface easily. These memories collide, entangle with each other often manifested in nightmares. But ‘magically realistic' disappearance of Najeeb Ahmad, a JNU student- has been buried in the piled-up files with dust in my memory – much like how his existence now confined in CBI’s closure file – lies somewhere with dust in an old Almira in a government office. When the state could not ensure his existence, didn’t console the grief of a mother, we the republic, live with the adrenaline rush changing every minute with the modern tech world. But my mind says, Najeeb exists elsewhere. That elsewhere is memory!

Trembling hands of Zakia Jafri used to pray and remember her husband Ehsan every year in February after visiting her old ‘home’ in Gulbarg society in Ahmedabad. Her home, love of life, belonging, neighbours were burnt to death in February 2002 Gujarat Masscare. Zakia could not see her husband after that afternoon in 2002, nor justice. In February 2026, her neighbours will pray for her too! Perhaps, the walls of her home feel more void and cracks than ever.

I am scared to lose these memory files in the world I live in today, defined by algorithms. I am extremely scared of their very existence. I aspire to record every human experience around me – not for the sake of stories needed to be told, but to understand and engage perseverance of human experiences, to decode them with every lens, to challenge the status quo and to imprint the invisible in my world of writing.

But many stories that I won’t be able to tell in my mortal life, should exist elsewhere – in human memories! In my Utopia, I defy and resist the erasure!

An Imaginary World Where There Is No Threat to the Climate

Let’s call this place “city”. Mizo comes down from the 50th floor of his swanky office, which, like most buildings in the city, is made of a glass facade, top to bottom, and is fully air- conditioned. He comes to the parking lot and immediately gets into his AC car; his body struggles to take the natural warmth of the sun. Through the closed window of the car, like every day, he watches the sun melting into the horizon. Like every day, that makes him smile. It adds some sparkle to his solitary, lonely and robotic existence in the city.

He reaches home and is surprised to see an invite at his doorstep. After decades, a physical invite, not an emailed one. He picks it up. After watering the plants and making himself a cup of coffee, he settles on his study table, overlooking a huge Banyan tree. He opens the envelope. There is an invitation to a piano concert. He reads the names of the three female performers. None sounds familiar. He thinks hard. He then faintly remembers a tiny girl in two ponytails. Her name was Misho. He knew her briefly. Their paths had crossed decades ago for a short while when they were 10-11. They went to the same academy. He would play soccer and she would learn the piano. They never interacted.

Why an invite now? An invite specifically addressed to him. Why would she remember him? She definitely went out of her way to find him and his address. But why? Was she interested?

He decided to go. He wasn’t particularly interested in the piano, but he felt like getting out of the city for a picnic. The concert was in a small coastal town close by. Let's call that place “town”. It was predominantly inhabited by fisherfolks and other simple people, but many affluent people from the city had built swanky summer homes by the beaches.

Mizo had been to the town a couple of times as a child. His father, a naval container engineer, would take him. Together, they had been to the museum and the lighthouse. They would buy fish and cream rolls and return in the evening on a ferry. His father loved the town, so Mizo wanted to go there in loving memory of his father.

He woke up early on Sunday. The concert was at 3 pm. He decided to take the intercity train, attend the concert, and take the last train back home. He wore a formal white shirt, black trousers and a jacket.

He bought a small bouquet of red roses at the station. He thought about Misho while waiting for his 11 am train. There were very few passengers and by the time the train reached the town at 1 pm, only three people got off. He felt sad. The Town used to be thriving once upon a time.

He walked to the nearest bus stop. He could smell the sea but could not see the sea. He remembered there used to be many seagulls back then. There were none now. Deserted roads and markets were other things that puzzled him. An empty bus arrived. When he asked for a bus ticket for the concert venue, which was on the top of a hill, the conductor looked at him suspiciously.

As the bus started moving uphill, he spotted the swanky summer homes. But there were no people inside. The iron gates were rotting, rusty cars were stationed outside and the gates were covered with dried brown weed. Still no sign of the sea.

The bus stopped. The conductor instructed him to get off. The bus took a U-turn and went away. He walked up to the concert hall. There was a huge iron lock on the main gate and it seemed it had been there for years. He peeped inside. There was a parking lot, but no cars. There was absolutely no one around whom he could ask. It was 2:45 pm. He took out the invite to check if he had got the date or the venue wrong. No. His mobile showed no signal.

He suddenly started feeling unwell, dizzy, as if he could not breathe. There was a small park nearby. He plonked himself on one of the benches. There was a thick layer of dust on each bench. There were no trees, no grass. There was only one rusted swing covered with weeds. He could see the abandoned lighthouse at a distance. The sea must be close by. With very little strength, he walked up to the edge of the park. He was horrified to see the view—the sea was near- empty; thousands of dead fish and other creatures were lying around. He threw up and came back to a bench and sat there with his eyes shut.

After a while, he felt as if someone had come and sat next to him. Startled, he opened his eyes and found a girl seated there. Not pretty, but attractive. Somehow, he could tell that she was Misho. He wanted to ask her so many questions, but he struggled to speak. Misho was just sitting there, staring at him with no expression. Her face was pale, almost white, as if she were a ghost. She handed over an envelope to him. Inside was written: “Welcome to the land of the dead. There are no trees. There is no water. All the birds have died, so have the animals. The earth is boiling. You, you all, are responsible. You must die.” Next, dozens of men and women came running towards Mizo, daggers in the hands. He ran until he could not feel his heart pumping.

He woke up with a jolt, drenched in sweat. He was in his bed, wearing the same white shirt. The bouquet of red roses was lying next to him. He opened his wallet. There were three bills in it—one in exchange for the red rose bouquet, a train ticket to the town, and a bus ticket to the concert venue. After a while, he opened the newspaper. In one of the inside pages was the news about the piano concert. Misho was one of the three girls.

Mizo took a month-long leave from work. The more he tried to make sense of that episode, the more surreal it seemed. Something, however, had broken inside him. He could not erase the image of the near-empty sea. He would spend hours thinking about the graveyards cities and towns were going to turn into.

He came up with a plan. Once a month, he would go to the Town with a bag full of seeds. He would sprinkle those in the parks and near the seashore. From his end, that’s all he could do.

Her And Our Imagined World

Her hands were calloused. I could notice from a distance the deep furrows on her face. I don’t know how she developed the double chin. The folds of her skin moved as she breathed laboriously. I felt she lived on a hill and had come running down to meet me, panting and breathing heavily. But she was there outside her small house, which had been built on flat land. She caressed her son and stroked his hair. Then she held her girl child in a tight grasp. She ran her eyes over a field that lay across the road separating her house, which had been enclosed by a low brick wall.

“Everything has been lost. The floods destroyed everything,” she said. The worry of how to earn a livelihood occupied her. Her face fell as she talked about the floods. It had rained heavily for a few days. She was happy as it began to rain on a hot afternoon in June. The sun had been beating down harshly, leaving her dismal, as she feared that her vegetable crop would be lost to prolonged drought. And when it rained, she felt that the earth would sprout with grass and relived the time when fields turned into a riot of colours as wild tulips bloomed and mustard crop produced yellow hues. She hoped for a better vegetable harvest and thought she would soon be in the field forking up land to remove the weeds and occasionally water them.

In the evening, she lulled her two children to sleep by reading aloud from a storybook about how a good crop ended the worries of a farmer who had been left famished by years of drought. It was as if the writer had foretold her story, as if the story mirrored her life. She pulled the warm blanket over her children as she put them to bed and turned off the lights. For two days, she was happy, but then on the third night, she could only imagine for herself the hard time ahead. The fields outside their house got waterlogged, and all her vegetable crops were destroyed. Only the dry twigs, which were draped with scraps of cloth to drive away the birds, remained.

“I don’t know what to do? Where would I get money to pay the school fee for my two children?” she told me. Vegetable crop was the only means of survival for Atiqa after her husband died in an accident while he was returning home following the day’s carpentry work.

Since then, she had lived with her brother-in-law, a stolid man with a rotund face and an unusually thin frame as if someone had forcefully put the head on the body and done a disservice to his countenance. The man had also lost his apple crop to the floods, but seemed to be less jittery and knew how not to betray his mind from his face. His apple orchard remained under water for days, and as he couldn’t drain it out, it damaged the trees after the root rot.

From a distance from where Atiqa’s house existed, a sonorous voice rose from a mosque, whose minaret was illuminated with green lights, as someone called people for prayers. Dusk began to fall as I walked through the fields covered with mud brought by the heavy flow of water as the floods breached an earthen embankment in Kashmir’s Pulwama area. I walked back to the cab stand, rode a horse cart for some distance and watched people shovel out sand from the Jhelum River, which had swelled and flooded Atika’s neighbourhood. I was told the floods washed away the banks of the Pulwama village and willow trees too. Now, I saw men rowing the boats filled with the sand that they had removed from Jhelum to sell it off.

I walked back home, wondering what Atiqa’s imagined happy world could be. On my way back, I was lost in thoughts on whether she would be able to feed her two children and send them to school. Months later, when I went back to Atiqa’s village, a grave existed next to her vegetable field. She had been laid to rest and had remained bedridden for several days before she breathed her last. I was told she had been suffering from multiple ailments. Before her death, she had found the means to survive, the means to raise her children. She got the embroidery work and managed to eke out a living. At the place which had remained waterlogged, her two children were smeared with dust as they played in the field. They had cried and screamed as her body remained shrouded in white, but someone had told them that she had turned into a star and was keeping a watch over them from the sky and would soon be converted into flesh and bones to return back. The children’s imagined world was to see that their mother would come back and lull them to sleep, reading out to them the stories from their storybook. The imagined world of Atiqa and her children had been mine too.

A Place Where I Shall Meet My Father Again

Death, in religions around the world, is seen as a journey after life—while for some, it is nothing more than worm food. When I lost my father in 2021, I didn’t know whether to believe in the journey or the worm-food theory. The only thing that continues to eat at me, four years after his demise, is that I don’t have him to share my achievements with, or my losses, or the things that bother me. I feel clueless. I feel an unexplained rage—a despicable hatred towards him at times. He isn’t there when I think I need his assurance or guidance. My mother keeps reminding me of his absence, even though I have become quite accustomed to it, because that is my only coping mechanism. It’s not normal—I am aware. You ignore your trauma long enough to have a once-a-year nervous breakdown. I have mine on his death anniversary, every time.

In many religions, everyone who dies is believed to embark on this after-journey towards hell or heaven. What has somehow made me feel better is the belief that I shall meet my father again in heaven. In my imagination, he is waiting for me under a tree, with his arms wide open and I run to him as I always did before he passed away; I hug him, sob my eyes out, and tell him about all the ups and downs of my life.

I shout at him for not staying long enough to see his kids become independent, make a name for themselves, and continue his legacy.

I tell him about all the plans I had for him and Ma—sending them off to explore new places, letting them spend time together after all their struggles, sending them for Haj together. All the things he never did for himself because he sacrificed everything for his kids. Me walking beside him forever... That’s my imagined place.

Remembering Nani Ka Ghar through Borrowed Memories

Earlier this year, while dusting the back of my father’s cupboard, I came across an old photograph of my elder sister cradled in my grandmother’s arms. I sent it to my sister with the caption, “You have a photo with nani.”

All my life, I have grown up on stories of nani ka ghar—the walls that are withering away, the doors that creak, the steady tick-tock of the old clock, nani ki kahaniyan, the china cabinet filled with treasured tea cups, the laddoo ka dabba and the endless servings of food.

Unfortunately, I never truly got to experience it. My grandmother passed away when I was a toddler, taking away her presence from the world and nani ka ghar from me. For me, it remains an ‘Imagined Space’.

As a premature baby, when my mother fell ill after delivering me, I was sent to my nani ka ghar. I am told I had the time of my life there during the first six months of my life. Needless to say, I have no memory of it. All that remains are stories—from my eldest cousin, who helped nurse me back to health alongside nani; from my mama, who says, “tum bina nani ke soti nahi thi”; and from my mother, who tells me, “Mata ne tumhara bohat khayal rakha hai.”

I only get to hear tales of it. I long for a life I have already lived, one whose textures I can almost taste, yet it feels like a memory implanted rather than lived. Nani ka ghar carries its own values and lessons. I hear friends say, “Nani ne achaar banana sikhaya,” and my mother reflects, “Mata ne humko itni azaadi nahi di jitni humne tumko di hai.”

For me, nani ka ghar exists only in borrowed memories, repeated sentences, and stories retold so often that they almost feel like my own...

I wish I had a photograph with her—the woman who made my mother who she is; who instilled in her the pride of independence, despite never having made the 60-km journey from Unnao to Lucknow herself.

My nani, who taught my mother what education truly means; a woman who was gone too soon.

I am certain she would be proud of my mother for raising two daughters, educated and independent. And even though her house remains an Imagined Place, the principles she bequeathed to me are anything but imagined.

A Candle Across the Kohistan-e-Namak

An entire mountain range made of rock salt. The first time my grandfather uttered the words ‘Kohistan-e-Namak,’ he conjured up an imagery that boggled my mind. As a seven-year-old resting under a quilted blanket with him in the winter chill, I thought grandpa was making up a story. I had no clue that a 300 km-long mountain range in the Punjab province holding the world’s largest deposits of pink Himalayan salt actually existed. But the tales flowed effortlessly out of his mouth and I looked at his withered face and one-and-a-half day old stubble with the wonder reserved for grandpas.

He said the range spread along the south of the Potohar Plateau and the north of the Jhelum River where his village was.

“If you lit a candle on one side of the mountain, you could see it from the other,” he said, even as I gaped at him.

He went on to share anecdotes about how my great- grandfather could pull a horse out of a well with its tail. The tales continued. His father would swim across the Jhelum every day for work. And then one day, the sailab took him. He died trying to rescue his son from the river in spate. From then, my grandfather developed a fear of water.

When the Partition uprooted our family, my grandmother took the train to Shimla, to another mountain, carrying my father. My dad, a Midnight Child, was conceived in the Jhelum province and born in Himachal Pradesh.

Even as I consider Shimla my home-town, stories of that village on the banks of the Jhelum that my grandfather told me refuse to leave my mind.

A newspaper assignment took me to Pakistan in 2004 for a cricket story. I got a single-city visa and returned home. But I still long to visit that riverside village and light a candle at the Kohistan-e-Namak. Till that comes true, the village will remain a place in my imagination.

Spaces Built from What One Has Endured

Spaces which exist only in the imagination. No fantasies, no mythical lands, no legends. These spaces are built out of the experiences:

Quiet rooms. Open windows. Mellow mornings.

Peaceful voices and calm breathes.

Sunlight is streaming in on the floor, a child sleeping without fear. There’re unpretentious smiles and uncomplicated joy.

Imagined places have: Women who survived, women who imagine, women who rebuild, women who didn’t explain.

Women laughing loudly because survival must also sound like joy. For them courage, like quiet fire. And love, that begins with themselves.

Imagined places are held close, built slowly and lived into.

When Nina Simone sings Feeling Good and you suddenly believe her because hope isn’t linear.

Some Urdu words that taste like ache: qurbat, rehmat and sabr.

Books stacked on the floor: Agha Shahid Ali, Parveen Shakir and Arundhati Roy. There’re dog-eared pages and many more stories that refuse to betray us.

Traces of perfume on winter shawls.

Snow from the homeland when the world refuses to be kind or the memories of almond blossom air.

Photographs of the person you once used to be. Prayers that no longer know what to ask for. Grace again because we keep trying. Hurt again because life keeps insisting.

Borders that don’t bleed and countries that do not punish the living.

At imagined places, tomorrow is kinder. Joy stays, Gaza lives and Kashmir heals.

Faiz Ahmed Faiz softly in the mind: “dil na-umeed to nahi, na-kaam he toh hai...”

Kindness of strangers:

Someone holds a door; someone pays a fare quietly; someone sends chai when the world collapses; and someone says 'I see you' without asking for your story.

Somewhere, Kendrick Lamar in the background, reminding us that survival can be defiant; that pain can speak without breaking.

That dignity is not a gift, it is claimed, even when bodies ache, even when the world trembles.

Even when small victories are swallowed by headlines.

At imagined have:

Dua, the everyday kind that keeps you standing;

Sura, half-remembered from the childhood, when the world trembles;

Tasalli, arriving without permission. And Tawakul.

A heart unafraid of hope.

Leonard Cohen on a rainy evening… “there is a crack…” and healing suddenly feels possible.

Roads that lead home even when you don’t know what home is anymore. And in your imagined places, you are not perfect. You are you. Unapologetically. You are enough. You are allowed. You are whole.

A Liminal Space

I once asked a favourite writer—famous, but not blinded by fame—how to write about this world while also being in it. How does one take in all the beauty and ugliness, all the kindness and cruelty, all the information and disinformation, all the innocence and intrigue, and find a way to weave it all into a coherent narrative? His answer set me off on a search: to find a place that is elsewhere, a place which offers a vantage point to all that is going on, but also offers a certain remove from all the storms that sweep across our seas.

This place isn’t on any map. Its latitude and longitude are not set by geographers. Its borders are fluid. It glides between the past and the present, between the real and the surreal, between the here and now and the hereafter. It stands still, it is quiet. But the silence is not the silence of the grave. The cries of the world can be heard from there, the colours seen, the rumbles sensed. Nothing is shut out, but nothing overwhelms. In this liminal space, fragmented thoughts coalesce. Ideas, buried deep in the mind, sprout like tender shoots. Stories take shape. Characters become flesh-and-blood figures. There is freedom to wander in this liminal space; room to let my mind out of its iron cage. To let go of jaded thought patterns; to cut through the everyday chaos and arrive at clarity.

Nostalgia Is Elsewhere

Champak Bhattacharjee

When I think of Tezpur, Assam, my birthplace, I don’t just remember a place—I remember a feeling. Slow mornings, green everywhere, fresh air, clear blue sky, rain that used to change the shape of my days. Life felt lighter. As a child, I lived in that real world and spent a lot of time with my friends.

Growing up took me far away from that world. Work, metros, deadlines—all real, all necessary. But somewhere, those earlier days in Assam stayed in my memory. I always imagine that I would go and live there again.

But today, that place has changed completely. I can't feel the same way about it and the way it was preserved in my memory.

Now, I always feel the place I want to live in is elsewhere—not in another country, but in that older space I once knew. An imaginary place shaped by nostalgia, where time moves slowly, and life feels great again. Like Assam once did.

Seeking Solace In Nature

Subhashree Rath

One of my earliest childhood memories happens to be that of taking an early morning stroll under the summer sun to pick flowers in a wicker basket. My grandmother would use these for her morning prayer. Little did I know that this ritual would cultivate my lifelong curiosity about the natural world. I distinctly remember the first time I wanted to ‘capture’ a moment—the home garden was drenched in fresh rain and little creatures buzzed and flitted about, 12-year-old me was fascinated by the fleeting formation of water droplets on leaves. There was no turning back; I would eagerly wait for it to rain in Bhubaneswar so I could see what nature had in store for me to capture with a point-and-shoot camera. It makes sense then that so many years later I continue to seek solace in nature. I am pleasantly surprised if I spot the moon or the rare star, twinkling in the Delhi night sky, watching over us city dwellers waiting to get home so we can stare at a bigger screen than the one we have at office.

My favourite place is now perhaps fiction, a world where I don’t have to document every crescent moon and tiny lady bug because I’m not sure how many more of these I will see.

In My Imagined Place, Memory Is Shelter

Mohammad Ali

I did not set out to imagine another country. I wanted only to write on the one I lived in. But somewhere along the way, the nation I thought I knew became harder to describe, and then harder to name. Words I had once used freely began to feel heavy in the mouth. Sentences arrived already rehearsed, already cautious. I found myself writing not what I saw, but what I could safely phrase.

That is how my imagined place began to take shape. It grew quietly, through small acts of subtraction. A word I chose not to use. A detail I softened. A paragraph I rephrased to avoid misinterpretation. Over time, the censor moved inside me, settling into instinct.

I am a journalist. Or at least, I used to think that was the most relevant thing about me. Increasingly, it is not. In public debate, online abuse, television studios, police paperwork, and casual conversation, my professional identity is overridden by something else: my religious one. I am not encountered first as a reporter, but as a Muslim reporter. Sometimes not even that—just a Muslim, fullstop. The nation has a way of shrinking you like this.

You are allowed to belong, but conditionally. Your grief must be measured, your anger moderated, your questions phrased carefully. You learn quickly that some stories will always be read as confession, not reporting; as grievance, not inquiry. This produces a strange form of internal exile. I live in the country of my birth, speak its languages, report on its institutions, and yet feel increasingly foreign to its official imagination. I have not crossed a border, but a border has crossed me. I carry it into newsrooms, courtrooms, airports, social media feeds.

The imagined place I inhabit now is built around this awareness.

It is a country of pauses. In this place, silence is not emptiness; it is a strategy. I know when not to speak, when to lower my voice. I know which words will trigger suspicion or surveillance, which will summon a mob of good-faith interrogators asking me to prove my loyalty.

The public language of the nation is loud, muscular, triumphant. Flags wave constantly. Slogans repeat until they sound like truths. As a journalist, this is disorienting. Journalism depends on friction—between claim and fact, power and accountability. But friction is precisely what the nation increasingly refuses. It wants affirmation, not inquiry. Participation, not critique.

I find myself returning obsessively to the past—not because it was better, but because it felt less surveilled. There were arguments then, bitter ones. There was violence. But there was also space to disagree without being assigned a permanent identity. Today, remembering that plurality feels almost subversive.

In my imagined place, memory is a form of shelter. I remember cities before they were renamed into uniformity. Neighbourhoods before they were policed into silence. Newsrooms where disagreement was expected rather than pathologised. These memories operate as proof that another way of being national once existed.

Violence, when it arrives, often does so indirectly. A threat on the phone. A message forwarded “for awareness.” A list circulating quietly. A case filed to teach a lesson. You learn to feel it before it happens. This anticipation changes how you walk, how you speak, how you choose your words. The imagined place I inhabit is attentive to these bodily cues. It is always alert, scanning. Exhaustion is part of its architecture.

Language fractures under this pressure. I notice it in my own writing. I rely more on quotation, less on assertion. I let others speak for me.

When direct speech becomes dangerous or futile, writing finds other routes. Allegory, memory, reflection, fragmentation—these are not aesthetic choices alone. They are survival tools.

My imagined place is a space where contradictions are allowed to coexist. Where I can be a journalist and a Muslim without apology. Where silence is chosen, not imposed.

Home, in this place, is unstable but real. It is made of friendships, shared meals, late-night conversations. It is sustained by those who recognise the difference between criticism and hatred, between faith and fanaticism. It exists despite the nation’s narrowing imagination.

This imagined place feels fragile. It depends on memory, language, and the stubborn refusal to surrender complexity. But for now, it is where I write from.

My Imaginary Landscape is Actually Real

A move to the hills means different things to different people.

For me, it was being able to reconnect with my parents.

Once I moved to my house-with-a garden in Kodaikanal, I invited my father over (he is the one who has land skills in the family). Within two weeks, he had cleared my backyard, planted some wild sevanthis (chrysanthemums) in my front yard to join the poinsettias, roses and hydrangeas. There is a plantain and a pink lily uncurling in my backyard, revealing one leaf at a time. We cooked together every day with fresh produce from the local Sunday market. I made notes, because none of these recipes are on the internet.

And we talked. Something we hadn’t done in years, decades. It helped that the frequent power failures induced many candle-lit evenings where he mostly spoke about his childhood, his aunts and uncles, working on the land with his father and his many travels on Indian Railways...

Legend has it that if you ever encounter a bison in the Palani Hills, there’s only one thing to do—step aside and wait for it to pass. It could take hours but wait you must, because everything is smaller in comparison to the bison—you, your car, the path to your home. Sometimes, I would spend hours watching a family of bison from my window or terrace until they were sated and left.

And then I realised, I don’t need an imaginary landscape to escape to. I live in it.

My Ancestral Village That I Never Visited

Animikh Chakrabarty

My father left Bangladesh in the middle of the night with a few tattered sacks, accompanied by his mother and grandmother and his ailing younger brother. The riots of 71 had spread over the land, including the village of Narail, where we had our ancestral home. I grew up in a small room, of a humble home my father managed to raise a year before my birth. We struggled as a family, with my father’s job in a jute mill, and my mother, still studying to get a job as soon as possible. At night, after work, my father would tell me stories of Narail, of the river that flowed past our ancestral house of generations, the fields, the mango trees. He would tell me how he used to go to the market to sell mangoes after my grandfather’s death, about the Durga puja in the village, his school, the vast landscape… He created this idea of Narail in my mind, where, if we had stayed, we wouldn’t have had to struggle as we did. Before falling asleep, I often wished I was playing with my father in the fields of our ancestral house. I could imagine him as a boy of my age.

I never visited Narail. I have been to Bangladesh, as an invited artist. I have been to many other places, but never Narail. I felt that the reality of the place will break my imaginary perception. It will not be enough for me, it will never be satisfactory.

A Space Where No One Else Can Enter

Jagisha Arora

Since childhood, there has been an imaginary place that lives in my mind—a place of my own. When the world grows too loud or stops listening, I go there quietly. It is a place where I exist without explanation.

In this place, there is a single flower pot with red roses. Beside my bed, there is a small shelf of my favourite books which are familiar and comforting. A music player plays the songs I love and melodies that seem to understand my moods. A writing desk stands nearby where I write without interruption. Here, I cook my favourite meals, and there is no hurry to do the dishes. No one is waiting. No one is watching. This place remains entirely mine.

This imaginary place was not escapism but survival. It held my fears, my loneliness, and my dreams.

It appears when I write—my very own imaginary place.

Elsewhere, Away from Everywhere Else

The idea of elsewhere is a very raw, feminine desire for me.

And when I think of my elsewhere, I think of ducks. The cute little yellow ducklings, the brown and white adults, some swimming, some asleep, some flapping their wings violently at their mates and attempting flights over the small body of water I own. Is it a pond or a lake? Pond, I think. Even in my fantasies, I do not own a parcel of land large enough to have a lake. Let’s have some realism in our fantasies. But there are trees, tall and dense forest walls in our escape from the world. It is protected by nature.

I yearn for this piece of land. It is my revenge against this world. The world that wants to stifle any desire among my kind. Where even owning land was not allowed for my ancient and long-dead sisters. But my imagined land will have a coven of sisters (witches). We will work the land. Not like Mother India. No, a lot more sophisticated because we won’t have to deal with an evil Lala. In fact, there will be no Lala of any kind, good or evil. This will be a reclusive space, an escape, from the world build by men, for men. This land is also my revenge against my relatives. It will look a lot like the land my father once owned. They first tried to plant semal and seesham. The roots failed. They then tried mangoes. Those, too, died.

The litchis, though, survived. And thrived. It was the sight of my father’s labours, his most prized possession. A spot where my sister and I ran through fields of mustard on terribly hot afternoons of the chilly winters; before departing to the madahi (shed) under the litchi trees where my father sat looking down at his jewels. Red rubies of litchi, yellow sapphires of mustard, green emeralds of guava, and strings of other vegetation living in between these.

I loved this place. It was where I met friends, all four-legged. The cattle of the villagers which came to graze. One time, a herd of goats befriended me. I started plucking litchi leaves from the lower branches to help my horned friends eat more. Too late I realised, there was a bee or a wasp’s nest. I was attacked brutally. Bitten all over my face and body for attacking their home.

The villagers from the musahar toli who lived around the orchard—slathered me in mehndi paste. I was orange for weeks.

But years passed, the mustard farm was sold to get some much-needed funds, the ganne ke khet gone during another financial crisis. All that remained was that litchi grove. The stubborn patch of Bihar’s most famous fruit next to a nala (drain).

The land, which he didn’t inherit but bought, was passed on to his youngest daughter—me. I was to go back, build it anew. Mushrooms. Maybe flowers. Something long-lasting perhaps? I settled on an idea. Wait till you get better, we go back, and chart out a plan. It will be a cold storage, a ginger farm, and a mushroom farm. He agreed. He rejoiced, his daughter was thinking of his legacy. Then, he died. He left me alone. The idea of reviving that land kept me going. Three years later, another shocker came my way. The land was ‘sold’, by a relative. It was ‘sold’ or promised to a Bahubali, Bihar is famous for them after all. There wasn’t much I could do. He must have assumed my father didn’t have sons so why not!

My ‘Elsewhere Land’, which is as real in my fantasies as the laptop where I type this, is planned as a two-fold revenge. One against this cruel world. One against the patriarchal relatives. No Twitter allowed on my land. We choose peace. We laugh as we grill the mushrooms we grew and the chickens we raised. We drink rum as we watch the sunset across a hill far away from our land. Our ducks have to sleep now. My dogs are awake, along with my coven, and we dance barefoot on moist grass till midnight. We wear our heart’s desires to cover our bodies; nothing for anyone’s gaze. Billowing robes of a forgotten medieval era to satin nightgowns well suited for a rich heiress. We don’t have to care. We just have to be.

The fire dies down to embers and embers are now being smothered by the foggy envelope around us.

I go inside, our mansion we built together. The lights are dim, we are away from people but not away from technology, duh! The light aches in our feet soon ebbs away as we cocoon ourselves in blankets made of fleece.

Ready for a new day. To harvest more mushrooms. To feed more chicken. To write my next best-selling thriller novel. To read till my eyes hurt. To feel safe in my coven and know no betrayals are imminent.

A Country Where My Friend is Free

A chilly night at the dhaba, where your breath turns to steam and goosebumps run through the breadth of your body; a bonfire, whose warmth seeps through your woollens, as if lifting your soul from a slumber; a cup of tea that keeps your enthusiasm invigorated as you shiver in the December winds; and friends talking into the night, without a care for when tomorrow arrives.

My favourite spaces have always been defined by the people who inhabit them. And nothing comforts me more than to recall the times that I spent with my friend, Umar, at our university, when he was a free man. When I think of a landscape that I would want to keep going back to, I conjure an alternate imagination of the five years that my friend has spent behind bars as an undertrial, for the crime of dissenting against the powers that be.

In that happy place, my friend is not hounded for who he is, not criminalised for what he believes, not persecuted for his wants and needs. There, we speak over each other incessantly in the heat of our arguments, we fight for what we think is right without fear and we laugh at the terrible jokes he loves to crack. In this imagined world, there are no limits to learning or to loving. There is no one to abuse or harass you for choosing a friend who happens to belong to another religion. You don’t live under a cloud of suspicion and hate for believing in something that others may not always agree to. It’s a place where smiles don’t perpetually carry the painful awareness that someone has been torn away from you and condemned to a life of isolation and infinite darkness. It’s a place that is just and free. Only in one’s imagination does this world come alive, but what a wonderful place it could have been!

Elsewhere, Where I Can Step Back And Find My Rhythm

X types out a few words, tilts his head, and looks at the screen. The gentle tap of the keys turns into a loud thud of the screen being shut. The anger at not being able to write is consuming. The despair palpable...In a bit, X reopens his laptop, looks at the screen, and toggles between the countless open tabs. This was his sixth piece of the day. He goes back to his published pieces for the day and reads the first one loudly enough to drown out the ticking clock. Research, facts, clarity—it has all of these. It reads well. X hides a smile and toggles back to the blank page on his screen. He still has three more to do for the day and must find a way. Taking a deep breath, he looks out of the window, staring at the city lights till they blur into oblivion. He snaps out of the short-lived daze. Reminds himself that it was only normal to feel frazzled. He has done good work and claws back to the dream he chases with every word he writes —of becoming a journalist who dives deeper into issues, asking difficult questions, holding people in power to account.

My imaginative escape is into a world where news isn't content, where traction doesn't control creativity, and where populating websites don’t define X's work. A world where the impact of the 24*7 news cycle is critiqued and where information overload is acknowledged.

My favourite 'elsewhere' is a land where X can choose to take a step back and find his rhythm without the ticking growing louder. A land where X is a journalist and gets to call himself one— where every word he writes reminds him of the reason he chose to pursue the profession in the first place.

The Pride Lands: Where Balance Matters More than Conquest

Frame9, TextboxMy favourite landscape is the Pride Lands—the fictional savannah at the centre of The Lion King. A vast swathe of golden grasslands, acacia silhouettes against burning sunsets, and Pride Rock rising like a witness to time—the Pride Lands are imagined as a world governed by balance rather than conquest.

What draws me to this landscape is how it visualises responsibility. The land flourishes when its ruler understands stewardship; it withers when power becomes extractive. In this sense, the Pride Lands feel less like fantasy and more like allegory. Seasons change, herds migrate, life and death are part of a visible cycle—a reminder that belonging to a place means recognising one’s smallness within it.

In a world facing ecological collapse and leadership crises, this imagined place continues to offer a quiet lesson: landscapes are not backdrops to human ambition, but living systems shaped by how we choose to lead, inhabit, and listen.

The Pride Lands stay with me because they ask a simple, unsettling question: what does it mean to deserve the land you stand on?

Multicultural Malaysia

S. S. Jeevan

When I went to Malaysia in 2005, I was told that the country’s landscape had been crippled by racial tensions. But it was only when I stepped out of the airport, I saw Malaysia’s amazing tryst with multiculturalism. Though an Islamic country, Muslims enjoy much more freedom than most other countries. Women wear the tudong—a tight drape framing the face—along with jeans or T-shirts. But it is not a mandatory dress code.

Pork and alcohol too are available in almost every part of the country. The multiculturalism manifests itself in the rendang that peacefully co-exists with the kway teow or the butter chicken in numerous food courts. And for a country with a huge ethnic minority—Chinese and Indian—Malaysia’s inclusive culture is truly remarkable.

Close to seven per cent of the country’s population comprises second and third generation Indians, most of them employed in the service sector. Indians came to Malaysia as illegal workers in the early part of the century. A growing number of new generation Indians now occupy Malaysia’s upper middle-class society, working as doctors, engineers and computer professionals. In many ways, Indians add colour to Malaysia’s multi-cultural society and they hope to get a bigger share of the country’s fast-paced developmental cake.