Posters proclaiming Chirag Paswan as Bihar’s “future leader” and the NDA’s new seat-sharing formula have unsettled Chief Minister Nitish Kumar, marking a symbolic decline in his party’s dominance.

Analysts say Paswan’s influence within the NDA has grown with BJP’s tacit backing, as many of his candidates are effectively BJP proxies — a strategy seen as paving the way for a post-Nitish power shift.

Internal discontent simmers within JD(U), with leaders accusing the BJP of deliberately empowering Paswan to weaken Nitish and prepare the ground for a BJP Chief Minister in Bihar.

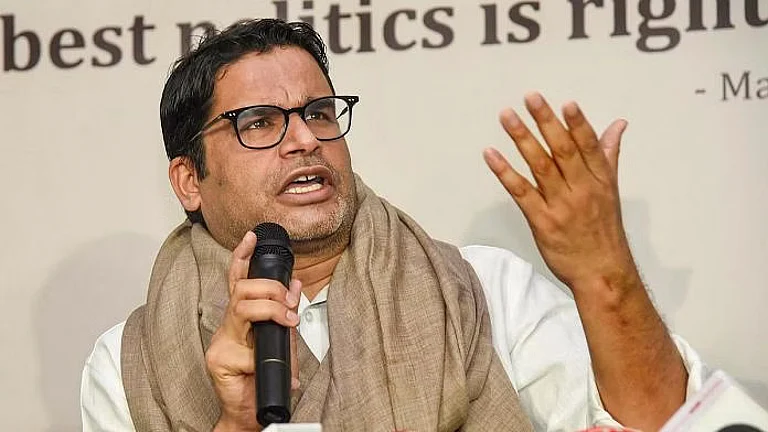

When political posters claiming ‘Bihar kar raha hai tajposhi ka intezaar, Chirag ke swagat ko Bihar taiyaar’ (Bihar awaits its coronation, ready to welcome Chirag) appeared across Patna in May this year, they set off quiet tremors in Bihar’s political circles.

The talk of “coronation” hinted at a generational shift and a possible new face in the state’s politics. The peppering of such posters across the state capital has made the JD(U) visibly uneasy, even as the BJP appears to be silent. Days later, Union Minister for Food Processing and president of National Democratic Alliance (NDA) ally Lok Janshakti Party (R) Chirag Paswan met Chief Minister Nitish Kumar and sought to play down the speculation, claiming: “This time, there is no vacancy for the post of Chief Minister in Bihar.”

That brief remark carried more weight than its tone suggested. Many saw it as Paswan’s way of quietly positioning himself as a future contender for Bihar’s top post. The question that followed was straightforward but significant: is the BJP backing Paswan as a long-term political bet, or is it using him to clear the path for its own Chief Minister in Bihar? The NDA’s seat-sharing announcement on October 12 brought that question back into focus.

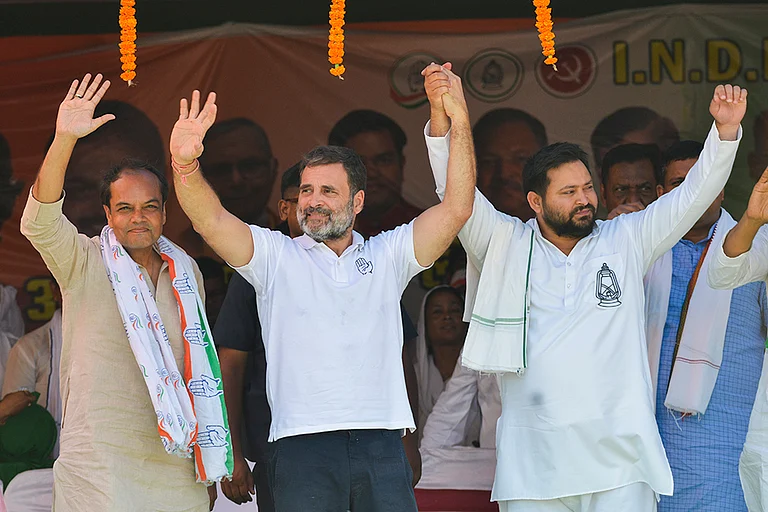

Across the aisle, the Mahagathbandhan is yet to settle its own equations. A month ago, it seemed Rahul Gandhi and Tejashwi Yadav had resolved their differences, but questions about the same continue to linger. With polling just weeks away and election campaign fervour nearing its peak, seat allocation arrangements between the Congress and the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) continue to be shaky.

Meanwhile, while the NDA may have formalised its own seat-sharing arrangement, the ambitious BJP’s constant jostling with the JD(U) over cornering of seats and the latter’s discomfiture with Paswan’s rise also suggests that ruling alliance’s feathers continue to be ruffled.

Under the seat-sharing arrangement, the JD(U) and the BJP will contest 101 seats each, while Paswan’s LJP (R) has been given 29 seats. The smaller allies, Hindustani Awam Morcha (Secular) and Rashtriya Lok Morcha (RLM) , will contest six seats each.

Amid reports of unease within the NDA, a senior JD(U) leader said his party had wanted Paswan to get the fewest seats possible, fearing that if the NDA and the opposition finished with similar numbers, Paswan could gain undue leverage in forming or unsettling the government.

Political analyst Mahendra Suman believes Paswan’s bargaining power has grown. “He enjoyed BJP’s tacit support even in the last election, when he contested alone. Most of his candidates were, in fact, BJP-backed and later rejoined the BJP,” Suman says. “It was Chirag who helped the BJP claim the ‘senior partner’ status within the NDA by damaging JD(U).”

Suman adds that many of the 29 LJP(R) candidates this time are effectively BJP nominees, which means the BJP is contesting 142 seats in practice. “The BJP’s goal is to form the government on the strength of those 142 seats,” he says. “If the JD(U) performs poorly, it will be Chirag who demands the Chief Minister’s chair.”

He also points out that the allocation of just six seats each to Jitan Ram Manjhi’s HAM and Upendra Kushwaha’s RLM is deliberate. If they rebel, their small groups of winning MLAs can be easily absorbed.

JDU Loses Its “Big Brother” Status

For the first time since Nitish Kumar came to power in 2005, the JD(U) is not the senior partner in seat distribution. In 2020, it contested 115 seats against the BJP’s 110. In 2010, the ratio was 141 to 102 and in the 2005 elections, the JD(U) contested 139 seats to the BJP’s 102. Even in Lok Sabha elections, JD(U) had held an advantage, contesting 24 seats to BJP’s 16 in 2004, 25 to 15 in 2009, and reaching parity at 17 each only in 2019. In 2024, JD(U) slipped slightly, contesting 16 seats to BJP’s 17.

“The BJP wants the JD(U) to win enough seats to remain relevant but not enough to dominate. Chirag’s strong performance will serve BJP’s long-term objective of leadership control in Bihar.”

This time, Nitish Kumar is said to have insisted that JD(U) contest at least one seat more than the BJP to retain psychological dominance, but that did not happen. The equal seat share marks a symbolic setback for the JD(U), and the 29 seats given to Chirag Paswan are being seen within the party as a greater concern than parity with the BJP.

Discontent remains within JD(U), though leaders have not expressed it publicly. One senior leader said off record: “Former state president Vishist Narayan Singh is deeply upset. His calls go unanswered. It seems Chirag has been deliberately empowered to sideline Nitish Kumar. The BJP is contesting 142 seats in reality to ensure JD(U) weakens, paving the way for its own Chief Minister.”

Allegations and Counterclaims

Following the announcement, reports indicated that Nitish Kumar was unhappy with the arrangement. Critics accused JD(U) working president Sanjay Kumar Jha of compromising the party’s position. MP Pappu Yadav wrote on X that Jha had “completed his mission to force Nitish Kumar out of the Chief Minister’s chair.”

Jha dismissed the allegations, saying: “Every NDA decision is being taken in consultation with Chief Minister Nitish Kumar.” He accused the opposition of spreading misinformation and planting false reports.

HAM leader Jitan Ram Manjhi, unhappy with his six-seat share, warned that the NDA would pay a price for underestimating him. He later echoed Nitish Kumar’s reported displeasure and announced that his party would contest two more seats independently.

Analysts See a Strategic Continuity

According to Pushpendra, a former professor at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai, the seat-sharing formula is not unexpected and follows the strategy adopted by the BJP in 2020. “Chirag was extremely useful to the BJP in 2020. He demonstrated his potential by weakening JD(U),” he says.

“The BJP wants the JD(U) to win enough seats to remain relevant but not enough to dominate. Chirag’s strong performance will serve BJP’s long-term objective of leadership control in Bihar,” Pushpendra adds.

“The JD(U) got roughly the same number of seats as in 2020 because, despite his frailty, Nitish remains both a necessity and a compulsion for the BJP, since it lacks a credible CM face in Bihar.”

On the BJP’s focus on Chirag, he says: “In 2020, Chirag’s priority was to defeat JD(U), while BJP’s agenda was to make JD(U) its junior partner. That experiment worked. Now, Chirag has proven himself a potent spoiler, perhaps even a potential winner under the NDA umbrella.”

Pushpendra, however, questions Chirag’s popular appeal. “His image hasn’t truly grown among the people, but the BJP’s promotion has amplified his presence. Chirag is not a banyan tree like his father, Ram Vilas Paswan, but he’s more like an Ashoka tree, strong but limited in spread.”

In the 2020 Bihar Assembly election, Paswan’s LJP contested 135 seats and won just one. But the party had fielded candidates against every JD(U) nominee. The outcome saw JD(U) reduced to 43 seats, while the BJP, with 74, became the largest NDA party for the first time. Analysts widely credited Chirag for JD(U)’s loss of at least 28 seats.

Even so, the BJP honoured its pre-poll commitment and retained Nitish Kumar as Chief Minister. In the subsequent cabinet expansion, however, all new ministers came from the BJP quota, with none from JD(U), signalling a clear shift in balance. Since then, JD(U) leaders have repeatedly sought a larger share of seats for the next election, but that demand has not been met, while Chirag’s share has grown.

The Road Ahead

An LJP(R) functionary, speaking on condition of anonymity, said: “Getting 29 seats is a victory for us. The JD(U) now fears that Chirag might avenge what they did to his father’s legacy, when Nitish Kumar politically sidelined Ram Vilas Paswan by creating the ‘Mahadalit’ category, excluding the Paswan caste grouping. But we believe Nitish ji will remain CM, for now.”

Mahendra Suman says Paswan’s fortunes remain linked to the BJP. “When the BJP wanted to weaken him, it promoted his uncle Pashupati Paras, splitting his party. Now it’s promoting Chirag again, leaving Paras isolated.”

He suggests the BJP is making use of the long-standing rivalry between Nitish Kumar and the Paswans, which dates back to 2005, when Nitish’s Mahadalit policy reduced Ram Vilas Paswan’s Dalit base.

Paswan, however, lacks his father’s ideological depth as a socialist leader. Charismatic but less grounded, his approach leans more towards image-building than grassroots politics.

Whether inside or outside the NDA, Paswan has remained Nitish Kumar’s most persistent critic, targeting his government on issues like crime and declaring he would contest all 243 seats in 2020. What stands out is the BJP’s quiet tolerance of Paswan’s criticism, a silence that appears deliberate rather than detached.

The shifting dynamics within the NDA suggest a larger political plan. With Chirag Paswan’s growing prominence and JD(U)’s diminishing stature, the BJP seems to be preparing for a change of leadership in Bihar. Whether Chirag becomes the face of that shift or simply its tool remains uncertain, but the “coronation” Bihar awaits may not be Nitish Kumar’s this time.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Md Asghar Khan is senior correspondent from Jharkhand

This story appeared as Game, Seat, Match, Outlook’s November 1 issue, which explored how the spirit of questioning, debate, and dissent—the lifeblood of true education—is being stifled in universities across the country, where conformity is prized over curiosity, protests are curtailed, and critical thinking is replaced by rote learning, raising urgent questions about the future of student agency, intellectual freedom, and democratic engagement.