Ratiram Manjhi was acquitted of Maoist charges in May 2022, but the shadow of those allegations has not lifted. A civil court in Bokaro cleared him in the Mahuatand police station case in which he had been booked on charges of murder, rioting and offences under the Arms Act and the Criminal Law Amendment Act. The verdict ended a long legal process, but it did not restore his life to what it had been. What remained were years of humiliation, shaped as much by police harassment as by social stigma. The consequences extended beyond him to his family. His two young daughters were denied schooling after a school withdrew their admission, thereby stalling their education for years.

Recalling the episode, Ratiram breaks down. In 2021, while he was out on bail, his daughters were selected for admission to a government residential school. “The school management told us to send them. But someone went there and told them I am a Maoist. After that, the school refused admission. My daughters’ education was derailed for three years,” Ratiram says.

Ratiram, a Santhali Adivasi, lives in Dakasadam village in Bokaro district, surviving on daily-wage labour. His wife sells vegetables in local markets.

After eight months in jail, Ratiram secured bail from the High Court, but the memory of his arrest continues to haunt him. He recalls being picked up in the early hours of January 14, 2015, when Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) personnel raided his home, accused him of killing a chowkidar in Mahuatand and subjected him to custodial torture before handing him over to the local police and sending him to Tenughat jail. He says the harassment continued beyond prison, with repeated CRPF raids on his home before and after bail, targeting his family.

Ratiram’s story reflects a wider pattern in Jharkhand, where thousands of Adivasis have been arrested on Maoist allegations and spent years in prison before being declared innocent. An RTI response shows that between 2009 and 2021, 704 cases were registered under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act in the state. Of these, 52.3 per cent involved Adivasis, 23.1 per cent OBCs and 6.7 per cent Dalits.

Hiralal Tudu and Surajmani were among those caught in prolonged trials. Both spent nearly 850 days in jail. Hiralal lost his mother while incarcerated, and even after securing bail in February 2018, he continued to shuttle between courts.

“I was in jail from September 2015 to February 2018. When I went to Tenughat jail, my daughter was only seven days old. Within a year, my mother died from shock while waiting for me. I couldn’t even see her one last time,” he says.

He recalls being detained by the police in connection with the 2014 Lalpania bus blast and held for three days, during which he was beaten regularly. Villagers who came to enquire were told that the police were acting under pressure and that it was a minor case. “They said they were making a ‘light case’ and I would be out in three months.” The pressure soon escalated into coercion. Asked to sign a document he was not allowed to read fully, he was sent to jail.

Between 2009 and 2021, 704 cases were registered under the UAPA in Jharkhand. Of these, 52.3 per cent involved Adivasis.

Surajmani and Hiralal, relatives from Tutijharna village in Gomia block, were accused of sheltering Maoists and storing weapons. Surajmani was only 25 when she returned from jail, but for years she lived, her family says, like a “living corpse”. Hiralal recalls trying repeatedly to speak to her, without any response. While others in the family married, no proposal came her way. The Maoist label erased her future. Their lawyer, Kundan Kumar Singh, says that under Gomia police station case no. 47/14, both were charged under multiple provisions of the Indian Penal Code, the Arms Act, the Explosive Substances Act, the Criminal Law Amendment Act and the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act. Both were acquitted in 2023. At the Tenughat court, Hiralal remembers the judge telling him, “Your case is over. You should focus on your life now and take care of your family properly.”

Yet for hundreds of Adivasis cleared after years in jail, the question of compensation remains unanswered. A familiar pattern runs through Jharkhand’s Maoism-linked cases, where Criminal Law Amendment Act Section 17 and UAPA Section 13 recur with striking regularity. Former Supreme Court judge Justice Madan B. Lokur has warned that the misuse of Section 13, which carries no safeguards, risks pushing the legal system into a “worse and worse situation.”

Human rights activists in Jharkhand say Maoism-related accusations and UAPA’s Section 13 are being increasingly deployed as a weapon against Adivasis.

Supreme Court advocate Abubakr Sabbaq, who handles UAPA cases, describes Section 13 as dangerously broad and vague. “Once an organisation is banned, even former members are seen through that lens. Suppose such a person visits your shop and makes an online payment. Based on that transaction alone, the police can apply UAPA Section 13 on you. Then you keep proving in court that the money was simply for goods purchased.” Sabbaq argues that the deeper structural problem lies in the absence of police accountability. When misuse carries no consequences, he says, it creates impunity, and impunity encourages repetition.

RTI data obtained by Prakash Viplav, secretary of the CPI(M)’s Jharkhand unit, underlines how this impunity operates. Of the 704 cases registered under the UAPA in the state between 2009 and 2021, 458 originated from the Special Branch, while 248 were registered by more than 100 police stations. Viplav notes that Section 13 of the Act was applied in 378 of the 458 Special Branch-linked cases, showing how heavily a single provision dominates Jharkhand’s UAPA framework. Viplav does not deny Maoist incidents occur or that police action is always illegitimate. But he argues that the larger reality is one of routine harassment of Adivasis, where the “fear of Maoism” is used to tighten control over land and natural resources. This pattern is most visible in West Singhbhum, the district with the highest number of UAPA cases.

Jharkhand holds nearly 40 per cent of India’s mineral wealth, and Chaibasa is home to some of the country’s richest iron ore reserves. Major mining companies operate in the region, including Tata Steel, SR Rungta Group, Shah Brothers and B.N. Khirwal Mines. RTI data shows that 187 UAPA cases were registered in West Singhbhum, followed by Dumka with 57 and Gumla with 42. All three are Adivasi-majority districts governed under the Fifth Schedule.

At the national level, caste-wise data on UAPA accused remains unavailable. In a 2019 reply in the Rajya Sabha, then Union Minister of State for Home Affairs G. Kishan Reddy said NCRB data recorded 5,922 UAPA cases between 2016 and 2019, but did not disclose the social background of the accused. This is why Jharkhand’s RTI-based data assumes significance, exposing patterns of targeting that national datasets obscure.

Prison data points to a broader national trend. According to the NCRB’s 2020 report, India had 488,511 prisoners, including 371,848 undertrials. Of these undertrials, 73 per cent were from Adivasi, Dalit and OBC communities, while 20 per cent were Muslims. A survey by Jharkhand Janadhikar Mahasabha documents how police frequently implicate poor and Adivasi people in Maoism-linked cases, often taking years for acquittals. In its 2022 report, the organisation found that in Bokaro’s Gomia and Nawadih blocks alone, 31 people faced such cases, many with multiple FIRs. The pattern extends beyond Jharkhand. In July 2022, an NIA court in Dantewada acquitted 121 Adivasis jailed for five years in connection with the Burkapal attack in Sukma, once again raising questions about policing under harsh laws like the UAPA.

Advocate Shalini Gera, associated with People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL), Chhattisgarh, says, “In the South Bastar division (Sukma, Dantewada, Bijapur), where Maoism was most intense, innocent Adivasis were made the biggest targets. The Jagdalpur Legal Aid Organisation analysed 1,446 cases from 2005 to 2012. Most were Maoist-related. The striking fact was that 96 per cent were acquitted, and there was not a single conviction in a Maoist case. Yet those arrested spent an average of three to four years in jail without guilt.”

Gera says that when police fail to build solid cases, they often fall back on “signature sections” to construct prosecutions, including IPC Sections 147, 148 and 149, Arms Act Sections 25 and 27 and Explosive Substances Act Sections 3, 4 and 5.

In Jharkhand, Adivasis remain under persistent suspicion, even when asserting constitutional rights. The Pathalgadi movement is a key example. Launched by Adivasis in Chaibasa and Khunti in 2017–18, it was met with a harsh response from the BJP-led state government. Then chief minister Raghubar Das termed it unconstitutional and alleged foreign backing.

Around 30 FIRs followed, naming about 200 people and booking nearly 10,000 as unknown accused. Sedition and other stringent sections were invoked, drawing criticism. Political divisions later emerged, and after coming to power, Chief Minister Hemant Soren ordered the withdrawal of these cases in his first cabinet meeting.

Sukhram, 50, who went to jail in this case, recalls, “They kept me in a cell for one month. The room was 12 feet long and seven feet wide. We slept there, ate there, and used the toilet there. After one month, they moved me to the jail barrack. I stayed there for two and a half years.” His voice breaks and he pauses before asking, “What was my mistake that they put me in a cell?” Sukhram Munda still cannot forget the night of 12 August 2018, when police picked him up at 2 a.m. from Patras Toli in Khunti. The arrest upended his family’s life. His elder son, Sukhnath, dropped out after Class 10. Livestock was sold, land mortgaged and savings drained as the family moved from court to court. Two pigs, two bulls, two goats and Rs 18,000 in savings were lost in the process.

Debates around the misuse of the UAPA place Jharkhand at the centre, given its large Adivasi population and the long legal battles many have fought to shed Maoism allegations. Chief Minister Hemant Soren has spoken against the law’s misuse, particularly after the arrest of 84-year-old activist Father Stan Swamy in the Bhima Koregaon case in October 2020 and his death in custody. Soren accused the BJP-led central government of using the arrest to crush dissent, noting Swamy’s work among the poor, marginalised and Adivasis.

Yet a contradiction persists. Despite being an Adivasi Chief Minister, Soren has not made a concrete political commitment on the UAPA, even as Adivasis form a significant share of undertrials in such cases. The NCRB data shows that between 2019 and 2023, 10,440 people were arrested under the UAPA nationwide, while only 335 were convicted, a conviction rate of 3.2 per cent. The same data indicates that UAPA arrests in Jharkhand have declined during Soren’s tenure, though the fall is sharper in neighbouring Chhattisgarh. Former IPS officer and minister Rameshwar Oraon says the law is frequently misused against Adivasis, with charge sheets delayed for years and bail effectively inaccessible in lower courts, forcing impoverished accused to approach High Courts they cannot afford.

Oraon suggests the state should adopt a broad policy approach. “In tribal areas, Naxalism has been a problem. But now, when Maoist activity is close to collapse, the government should review each case separately. And where evidence is weak, and acquittal seems inevitable, people should be released. This should be done not only by Jharkhand, but also by Odisha, Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh.” Oraon adds that in many cases he encountered during his years in service, the only “crime” of Adivasis accused of Maoism was that, under Maoist pressure, they cooked food for them.

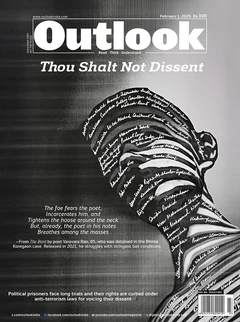

This article is part of the Magazine issue titled Thou Shalt Not Dissent dated February 1, 2026, on political prisoners facing long trials and the curbing of their rights under anti-terrorism laws for voicing their dissent.