Summary of this article

A Bhangar movement activist describes repeated arrests, UAPA charges and how new cases are used to prevent release from jail.

The essay exposes jail and police custody as systems designed to exhaust, intimidate and break political dissenters.

Even after bail, activists live under constant uncertainty, with dormant cases hanging over their lives and futures.

I am being released from jail after almost five months. I already know that many comrades and supporters have gathered outside after hearing the news. Along with me, several other prisoners are being released as well. Most of them are accused in minor cases. I, on the other hand, have many cases against me—among them the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA). Not all of these cases were filed earlier; many were slapped while I was already in jail. Whenever the government sees that bail is being granted in some cases and that release may be imminent, more and more new cases are filed. The intention is clear: not justice, not investigation, but to keep someone imprisoned for as long as possible, at any cost.

Getting into jail is easy; getting out is not.

First, bail must be granted by the court. Then the paperwork has to reach the jail. After that begins endless bureaucracy.

Meanwhile, prisoners are ordered to line up outside the office building beyond the main jail campus. Names are called one by one, signatures taken, forms filled here and there—it feels like an Ashvamedha sacrifice. It is summer. We are drenched in sweat, and amid this heat, a ritual of “prisoner-verification” is underway.

Finally, my turn comes. The duty officer is someone I recognise. He makes me sign papers and repeatedly verifies all the personal details I had provided when entering jail—my father’s name, address, and so on. He also checks physical marks noted at the time of entry: a scar on the forehead, a mole on the cheek. Time keeps passing. I begin to fear that yet another fresh case might arrive in the meantime.

I ask him, “Why all this fuss?”

He replies, “You wouldn’t understand. We have to make sure that the same person who entered jail is the one being released. Otherwise, I’ll lose my job!”

In other words, his only concern is that the correct person is released against the correct paperwork. His answer makes me smile. Being a Buddhist Marxist, I know that everything changes every moment; nothing remains the same. So I tell him, “The person who enters jail never comes out; the one who comes out is someone else.”

He stares at me silently for a few seconds, and then says, “The things you people say—I can’t understand any of it!”

But it is true. The person who enters jail and the person who comes out are worlds apart. Jail is a place that either forges you into steel or crushes you completely. In most cases, it is the latter—especially for activists. A major reason is the drastic change of environment. Of course, there is the loss of freedom itself, but imprisonment becomes unbearable mainly because of the surroundings.

These days, extreme physical torture in jail is not common—at least not yet. What the future holds is another matter. As the country rapidly slips into the grip of fascism, much will change. For now, jail appears relatively “normal”. But every single day is a trial by fire.

Most political prisoners today come from middle-class families. The overcrowded, unhygienic, unfamiliar chaos of jail life and the maze of rigid rules are utterly unbearable at first. There are all kinds of people inside. Most are accused in petty cases; many are there due to family disputes. But there is no shortage of people with a hardened criminal mentality. Learning to coexist with them on a daily basis is a major challenge. And among these crimes, the number of rape cases is disturbingly high.

The situation improves somewhat when the number of political prisoners increases. Then it becomes possible to shape the environment a little in one’s own way—to live together, build a sense of community, spend time in the library, observe occasions like the birthdays of Rabindranath Tagore or Karl Marx, publish wall magazines, form music groups, and so on. During my time in jail, our numbers were sufficient to do all this.

I can imagine that in the 1960s and 1970s, when political prisoners spent long years in jail, life was somewhat more bearable than it is today—mainly because of their sheer numbers. Those who are now forced to remain in jail for years on political grounds are truly worthy of respect. They survive, they eat and live, but the spiritual existence of political prisoners in today’s jails is genuinely under threat.

The government knows this. That is why it tries to keep political prisoners behind bars for as long as possible by entangling them in case after case. In most instances, the government fails to prove even a single charge. Eventually, the political prisoner is acquitted in all cases and walks free. But by then, perhaps a decade has passed.

When you finally stand on a free pavement under an open sky—the same sky and pavement you had gazed at like a thirsty bird while being ferried to court in caged police vans at fixed intervals—you wonder whether you will be able to take risks again. That is a form of spiritual penance. It will prove whether you emerged as steel or were quietly crushed inside.

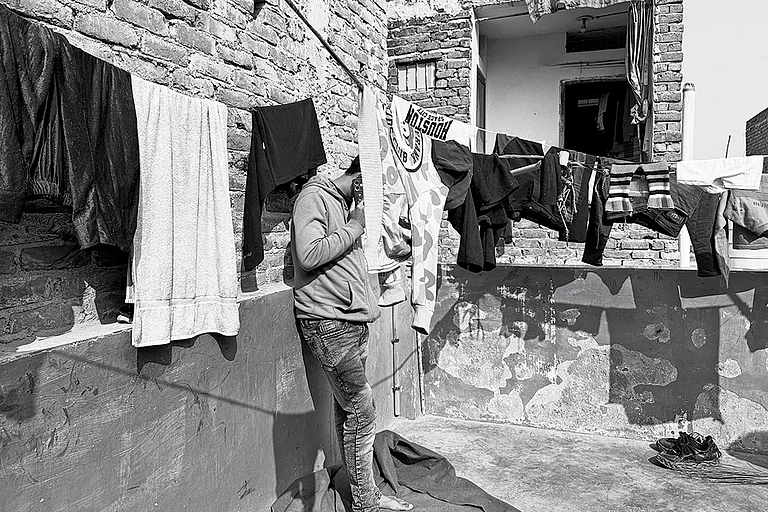

This ordeal becomes even more severe when numerous cases are slapped on you. Being released from jail on bail does not mean that the cases are over. You remain in limbo until they are disposed of. For those of us who were involved in the Bhangar movement, this reached an extraordinary level. Nearly 75 cases were filed against us. They included serious charges of every kind—UAPA, murder, attempted murder, and more.

After being released from jail, we had to report regularly to the police station for the first few days. We also had to appear in court on a routine basis. After my second release from jail in 2018, the Union Ministry of Power and the Power Grid authorities accepted a large part of the movement’s demands, leading to an understanding with the West Bengal government. As part of that understanding, the 11-point set of conditions we had put forward included the withdrawal of all cases. Accordingly, many cases were withdrawn. However, the UAPA case remained.

Although the remaining cases are currently dormant, there is no guarantee that they will not resurface and cause trouble in the future. As a result, while it is true that we have not had to go to court since 2019, the uncertainty remains. In reality, when you protest against the actions of the government, the government will inevitably retaliate against you. It will harass you in various ways, with the primary aim of forcing political submission. In a regime ruled by oppressors, nothing else can be expected. We learned this lesson at the very beginning of our political lives, and we have learned it repeatedly.

My first jail experience was in 2008, during the Left Front regime. We were falsely implicated in a murder case involving a trade union movement. After three months in jail, we got bail. The case dragged on for eight long years, and finally collapsed. We were acquitted. But the harassment, the financial ruin, the endless court appearances—it all took an enormous toll. Harassing political opponents like this is standard practice for all governments. The aim is simple: to push people away from the path of protest.

That time, I was not taken into police custody—imagine, a murder case, yet no police remand. The case was that weak. Still, I had to endure the hell of jail and eight years of relentless harassment.

I first experienced police custody in 2017, during the Bhangar movement. I was jailed twice; the first time, I spent 19 days in police custody, followed by 10 days in CID custody. Those 20 days were something else entirely. Jail custody is one thing; police custody is indescribable. The medieval conditions of police lock-ups are beyond the imagination of anyone who has never been there. Filthy blankets crawling with bedbugs and strange insects, dark and unhealthy cells, bathrooms that are 80 per cent open and utterly filthy. Food consists of a plate of rice, watery lentils, and a sprinkle of chili powder. When I pushed the plate away and said I wouldn’t eat it, an officer said, “What can I do? The government allocates three and a half rupees per meal. I’ll arrange an omelette for you from my own money.”

Political prisoners may sometimes manage alternatives, but ordinary innocent people cannot. Remember, those kept here are not convicted criminals. Many will eventually be acquitted. Most cases will not even stand. Then on what grounds must they endure such hell? Could police custody not be made humane and hygienic? Of course, it could. But it won’t be. These places are deliberately kept as hellholes so that once a person enters, they are broken completely—so much so that they never again dare to attract suspicion. This entire system of engineered suffering is the state’s machinery for producing “good citizens”.

Eight months after being released in August 2017, I was jailed again—back to Alipore. Old friends who were still inside raised a cheer. Those who enter jail freshly from outside still carry the scent of open life on them. Everyone rushes to absorb whatever little of it they can—snippets of news from the outside world.

Inside, however, the news is grim. Alipore Jail is about to be shut down. An old jail means sheltering within history. This cell housed Subhas Chandra Bose and Jawaharlal Nehru. Here, the gallows are written in the blood of countless revolutionary comrades. Ordinary prisoners may not care about these things, but for political prisoners, they are glaciers of strength and inspiration. That strength, too, is being taken away.

Now there is a new jail in Baruipur. Alipore is gone. How long Presidency Jail will remain is uncertain. And the fascists are engaged in a grand project of erasing history itself.

Despite all this, people will still protest. They will resist. They will fight, die, go to jail—again and again. They will remain in jail. And they will learn from jail.

(Views expressed are personal)

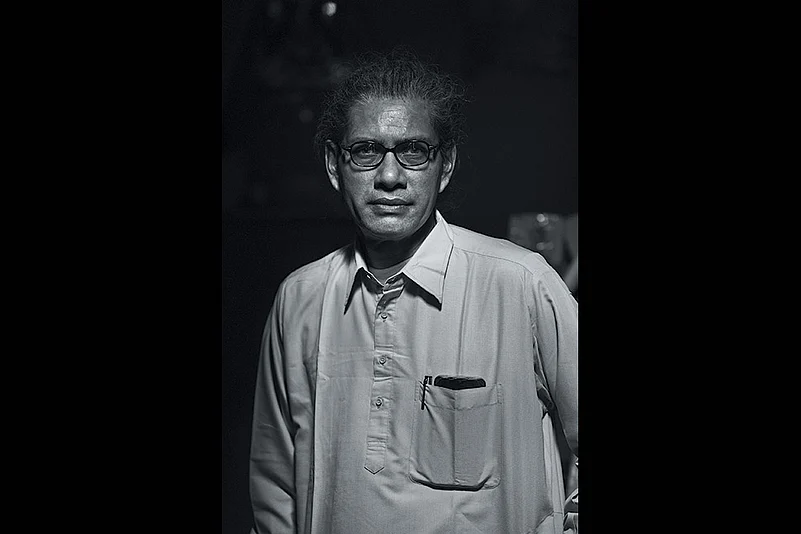

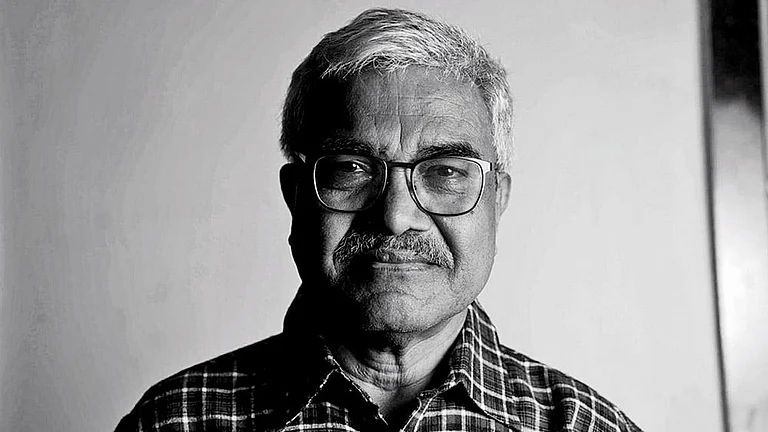

Shankar is a member of the Bhangar movement that opposed the construction of a high-voltage power grid substation in West Bengal due to land acquisition, environmental concerns, and lack of consultation, Shankar has been arrested multiple times for serious charges of every kind—UAPA, murder, attempted murder, and more. He is out on bail.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

This article is part of the Magazine issue titled Thou Shalt Not Dissent dated February 1, 2026, on political prisoners facing long trials and the curbing of their rights under anti-terrorism laws for voicing their dissent.