Upper castes overwhelmingly voted for NDA, while Yadavs showed near-total loyalty to RJD-led Mahagathbandhan.

While critics see RJD’s Yadav-heavy strategy as alienating EBCs and minorities, supporters argue it sustains the party’s grassroots strength by relying on its most loyal and mobilized base.

From marginalisation to dominance, Yadavs’ political journey reflects their transformation into Bihar’s most organised and assertive caste bloc.

The RJD’s relationship with the Yadav community goes far back, beyond Lalu Prasad Yadav’s reign. As debates over RJD’s “Yadav-centric” strategy intensify, experts remain divided on whether it’s a political strength or a costly miscalculation.

In the 1977 Bihar Assembly elections, the Janata Party won 214 out of 324 seats — a landslide victory. With this mandate, the Janata Party formed the government and socialist leader Karpoori Thakur took the oath as Chief Minister for the second time. Interestingly, at the time of his victory, he wasn’t a member of either House of the Bihar legislature.

RJD & Yadavs: How It Started

First-time MLA Devendra Prasad Yadav vacated his Phulparas seat in Madhubani district for Thakur to contest. The constituency, dominated by Yadav voters, saw a heavyweight contest: Karpoori Thakur versus Congress stalwart Ram Jayapal Singh Yadav.

Thakur not only continued Janata Party’s winning streak in Phulparas but also widened the victory margin, reportedly winning by over 65,000 votes.

Historically, Phulparas has often elected candidates from the Yadav community. Yet, in the politics of the 1970s, Yadav leaders were not identified as such, unlike the post-1990s phase, when caste identities became central to Bihar’s politics. Back then, several backward castes united under the broad banner of socialism, collectively challenging Congress’s long dominance.

Congress leaders like Ram Jayapal Singh Yadav and Ram Lakhan Singh Yadav were known for their broader political identities—not primarily as Yadav representatives.

By the 1980s, socialism was entrenched in Bihar. The 1990s Mandal Movement transformed politics, shifting power toward backward classes. Lalu Prasad Yadav became the most influential leader and Chief Minister.

While Lalu Prasad championed social justice and the empowerment of backward and Dalit communities, over time, he came to be seen as the leader of a narrower social base — primarily Muslims and Yadavs — giving rise to the now-famous MY (Muslim–Yadav) equation. That period also marked the deepening of caste-based politics in Bihar.

Writer and former RJD MLC Prem Kumar Mani, once close to Lalu, recalls, “Lalu was indeed a national leader of the backward classes. But later, he increasingly leaned toward the Muslim-Yadav bloc, particularly the Yadavs. In doing so, he limited himself to being a leader of one caste.”

Mani criticises the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD)’s current ticket distribution as overly Yadav-centric, arguing that the process now unfairly prioritizes Yadav candidates over those from other castes. “Earlier, Lalu ensured fair representation to all castes in ticket distribution. But gradually, Yadavs began to dominate the candidate list,” he says.

For the 2025 Assembly elections, RJD is contesting 143 of Bihar’s 243 seats. Of these, 52 candidates (36.36%) are Yadavs, though Yadavs make up 14.26% of Bihar’s population—about 2.5 times their demographic share.

Prem Kumar Mani, however, calculates it differently: “Excluding the 19 seats reserved for Scheduled Castes, RJD awarded 42 per cent of tickets to Yadavs, compared to Muslims (18 per cent of the population) and Extremely Backward Classes (EBCs, 36 per cent), both notably underrepresented. Even if RJD contested all 243 seats, Yadavs' share should be about 35 per cent.”

The 2023 Caste Survey of Bihar shows that backward classes together form 63 per cent of the state’s 13.7 crore population — with 36 per cent EBCs, 19.65 per cent Scheduled Castes, 18 per cent Muslims, and around 10.5 per cent upper-caste Hindus. Despite EBCs being the single largest bloc (4.7 crore people), both major alliances have failed to give them representation proportional to their strength.

RJD halved EBC representation from 26 to 11 candidates out of 144 seats. Koeris (Kushwahas) doubled from 8 to 16, Vaishyas jumped from 2 to 8, Bhumihars from 1 to 6, Rajputs fell from 8 to 6, Brahmins rose from 1 to 3, and Muslims from 18 to 19.

After the caste survey, the Mahagathbandhan (Grand Alliance) had popularised the slogan: “Jiski jitni abaadi, uski utni hissedari” (“Representation in proportion to population”). But RJD’s ticket distribution belies this — except for Muslims and EBCs, most castes have been given more than their share, with Yadavs topping the list.

Mani adds pointedly, “Lalu always invoked the MY formula, but the real beneficiary was always the ‘Y’.”

From Mandal to Nitish: The Rise of EBC Politics

Since the caste survey, EBCs (Extremely Backward Classes) have dominated Bihar’s political discourse. For decades, they were subsumed within the broader OBC (Other Backwards Classes) category. It was Nitish Kumar who, after coming to power in 2005, carved them out as a distinct political constituency — reserving seats for them in panchayat and municipal elections. He also divided Dalits into Dalit and Mahadalit, and Muslims into Pasmanda. This strategy helped Nitish consolidate a new base, eating into Lalu’s old backwards-class support.

As a result, in 2010, Nitish’s Janata Dal (United) [JD(U)] secured 115 seats with 22.58 per cent of the vote, a historic victory.

Since then, Bihar’s contest has shifted from forward vs backward to OBC vs EBC — a struggle within the backward classes themselves. Many EBC groups drifted away from RJD because they felt marginalised within the OBC bloc.

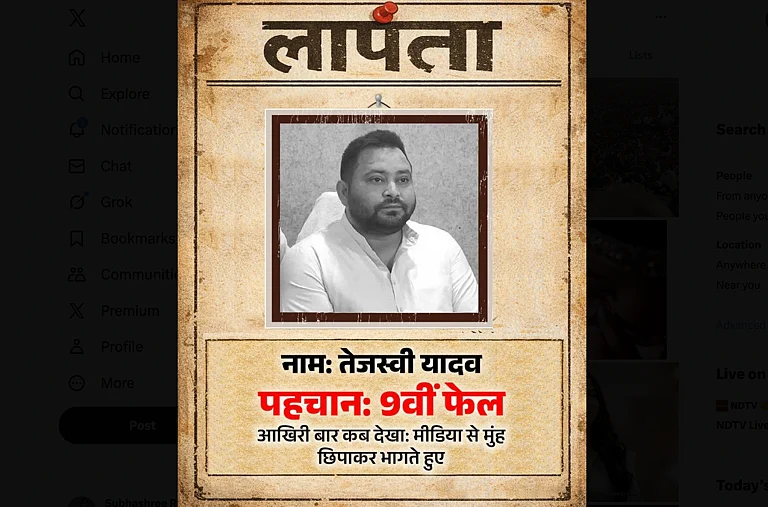

Tejashwi Yadav has tried to repair this image by projecting RJD as an A-to-Z party. In 2024, he appointed Mangli Lal Mandal, an EBC leader, as RJD’s state president — signalling outreach. Yet the numbers tell another story: RJD gave EBCs only seven per cent of tickets —roughly five times their population share —while Yadavs continued to dominate.

Political analysts argue that EBCs remain a fragmented bloc, over 100 castes, most with less than one per cent population share each, making cohesive representation difficult. Thus, parties often avoid giving them tickets, instead appealing to them through welfare or symbolism.

Yadavs as RJD’s Core Cadre

Electoral researcher Aamir Raza explains, “The Yadav community has always been RJD’s core base. Even when Muslim votes have occasionally drifted toward Congress or JD(U), Yadavs have remained remarkably loyal. Post-1990, around 80 per cent of Yadavs consistently vote for RJD.”

He adds that this loyalty is not just emotional but structural, “A party’s foundation can be ideological or sociological. For RJD, its very structure rests on Yadavs. RJD, as a party, and Yadavs, as a voting bloc, complement each other. One sustains the other.”

According to Raza, Yadav voters in Bihar, like in Uttar Pradesh with Mulayam Singh Yadav’s Samajwadi Party (SP), rally unwaveringly behind their most powerful caste leader. Even when Muslims or other groups shift temporarily, Yadavs stay put.

Raza further notes, “Nitish Kumar still holds a stronger appeal among EBCs and women voters. RJD likely knows it cannot win them over in a few months. So instead of distributing more tickets to EBCs, it reinforced its loyal Yadav base to stay electorally intact.”

Bihar Political Parties Comparison: Who Favours Whom?

Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), contesting 101 seats in the NDA (National Democratic Alliance), has given 49 tickets to upper castes — nearly 50 per cent. Excluding 11 reserved seats, the share goes up to 54 per cent, over five times their population share.

JD(U), with its Koeri–Kurmi base (7.07 per cent population), has given them 24.75 per cent of its 101 tickets — roughly three-and-a-half times their share. JD(U) gave 22 tickets to EBCs, the most of any party.

Congress, lacking a stable vote bank since the 1990s, has fielded 61 candidates within the Mahagathbandhan. Out of its 71 candidates in 2020, 34 were upper-caste; this time, only 21. But despite championing proportional representation, it has given EBCs merely 11 per cent of the tickets.

Voter Behaviour by Caste (CSDS Post-Poll 2020)

According to the CSDS (Centre for the Study of Developing Societies) post-poll survey, 52 per cent of Brahmins, 51 per cent of Bhumihars, 55 per cent of Rajputs, and 59 per cent of Kayasthas voted for the NDA, while only nine to 19 per cent voted for the Mahagathbandhan.

In contrast, 83 per cent of Yadavs voted for the Mahagathbandhan (mainly RJD), with only 5 per cent for NDA.

Among Kurmis (Nitish Kumar’s caste), 81 per cent supported NDA; Koeris/Kushwahas gave 51per cent votes to NDA and 16 per cent to Mahagathbandhan.

The Yadav Question: Political Necessity or Overreach?

Senior journalist Manikant Thakur, who has been observing Bihar’s politics for over four decades, believes that the RJD’s list of candidates once again reflects Lalu Prasad Yadav’s bias toward Yadavs and his family. Thakur says, “This time too, Lalu Prasad continued his tradition of favouring Yadavs in ticket distribution. But this time, he will have to pay a political price for it. In recent years, politics around Extremely Backward Castes (EBCs) has intensified, and giving such a large number of tickets to Yadavs at this juncture is a major blunder.”

“The second blunder the RJD made was to increase the number of tickets for upper castes merely to maintain its ‘A to Z’ image. But this was done by reducing the share of EBC candidates. For instance, the number of Bhumihar candidates has been raised from one to six, and Brahmin candidates from one to three. This sends a clear message among EBCs that Lalu has favoured exactly those two social groups—the Bhumihars and the Brahmins—whom EBCs traditionally distrust the most.”

Thakur further adds that the RJD’s ticket distribution strategy may backfire, and that even the Muslim community feels betrayed by the party this time. As Bihar's political landscape shifts toward greater representation for EBCs and with long-standing alliances under strain, the RJD’s Yadav-centric approach faces unprecedented scrutiny. The party’s electoral choices in 2025 will not just test its traditional loyalties but could define its relevance—and survival—in an evolving caste-driven democracy.

However, senior journalist Vishnu Sharma defends the Yadav focus, “There’s nothing wrong in it. RJD is a mass-based party, not a cadre-based one like the BJP or Left. Its cadre is the Yadav community. If it doesn’t give them tickets, who will mobilise votes for it?”

Sharma adds, “Lalu gave the Yadavs political muscle and dignity. They are not a passive vote bank but an assertive, fighting caste — they vote like a disciplined cadre. You may call it Yadav's obsession, but politically, it’s rational.”

From Margins to the Mainstream

Before Independence and for decades after, Bihar’s politics was dominated by Congress and upper-caste elites — Brahmins, Rajputs, Bhumihars, Kayasthas. Yadavs, though socially strong in villages, lacked organised political power. Leaders like Ram Lakhan Singh Yadav and Ram Jayapal Singh Yadav held influence, but the community as a whole was not politically cohesive.

The JP Movement (1974–77) and the Janata Party government (1977) disrupted this old order. Out of this upheaval emerged Lalu Prasad Yadav, who redefined Bihar’s caste politics. His rise marked the arrival of Yadavs at the political centre stage — as architects, not just participants, of governance.

By the 1990s, the Yadav community had consolidated its influence in administration, policing, panchayats, and party structures. RJD became their natural home — a party of and for Yadavs.

Even today, while Nitish Kumar’s JD(U) has balanced caste equations by empowering EBCs, Yadavs remain one of Bihar’s most politically organised groups — and RJD’s unshakeable backbone.