The Bihari use of hum reflects a collective ethos that resists individualism, fostering solidarity across caste and class divides.

Generations of leftist and socialist mobilisation—through leaders like Lalu Prasad Yadav, Nitish Kumar, and Ram Vilas Paswan—have shaped an “ethical politics of hope” built on dignity, inclusion, and perseverance.

Despite economic hardship and political instability, Biharis continue to embody active hope—returning home to vote, maintaining communal harmony, and engaging in politics that seeks a better collective future.

Among the many taunts levelled against Biharis by other Indians is their insistence on using the collective hum while referring to themselves as individuals. Whereas other Indians speak of themselves in the first-person singular (main, aami, naan), the Biharis’ hum invites routine derision. Undaunted, however, Biharis resist the individualising pronouns that carve the rest of us into atomised beings whose identities are contained in our respective bodies and end in the tips of our fingers. In doing so, they remind us of the importance of living together despite our troubles, our differences and disagreements, and failings. Hum encompasses a solidarity that teaches us to look beyond our immediate selves, to make connections with others, and appreciate how people make meaning of life in conversation with one another.

The solidarity intimated by hum signals the Biharis’ ability to broaden their political horizons instead of confining themselves. Politically fostered by generations of leftist mobilisation that challenged the caste-class hierarchies cemented by colonial and postcolonial governments, such solidarity brings together the State’s diverse social groups in a shared struggle for a better life. Spotlighting their shared struggle neither detracts from the passionate ways in which political Biharis disagree with each other nor blurs the deep ideological fault lines that divide them. Rather, a recognition of their shared struggles helps to understand, and appreciate, the ethical politics of Biharis across the ideological spectrum: the scramble across the left, right and centre to claim credit for the caste census conducted in the State back in 2022 offers a case in point. Hum offers a cultural repertoire on which Biharis can draw to fashion and finesse their ethical politics.

An ethical politics champions not only what appeals to individual voters but also what is right for society. It goes beyond bargains over the loaves and fishes of office to highlight, demand, and advance a social agenda that becomes the focal point of public deliberation, and contestation. An ethical politics builds solidarity by not shying away from disagreement but actively inviting it so that the opposing viewpoints can be collectively examined and debated: the point is not to reconcile those viewpoints but to think together, despite difficulties, about building a better future together. Indeed, an ethical politics compels conversation around what a “better future” would even look like.

Hum encompasses a solidarity that teaches us to look beyond our immediate selves, to make connections with others, and appreciate how people make meaning of life in conversation with one another.

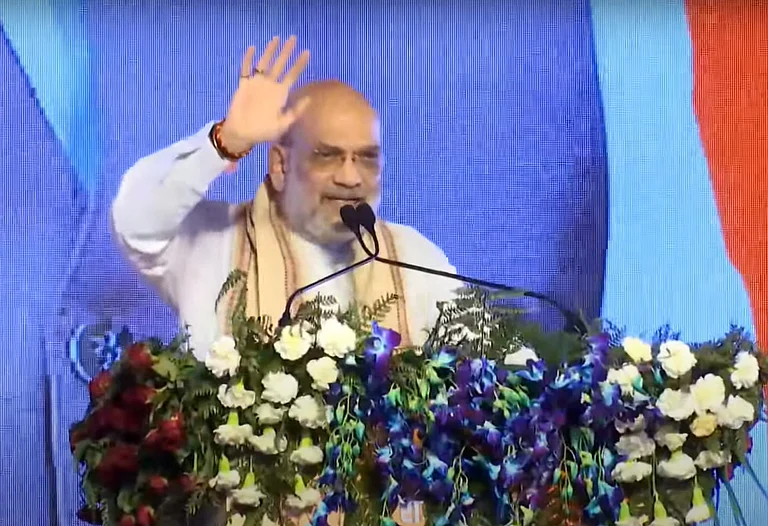

Bihar’s century-old leftist mobilisation offered some clues. Including within its ambit such figures as the ascetic-activist Sahajanand Saraswati, the socialist Karpuri Thakur and the communist Jagdish Mahto, these movements paved the path for the emergence of such an ethical politics: their collective legacy is claimed and shared by several of the State’s political parties, including the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) and the Janata Dal (United). While the RJD, under Lalu Prasad Yadav, introduced the vocabulary of dignity across the Bihari countryside where some of the poorest people on the planet dwell, the JD(U) under Nitish Kumar sustained it through investments in social opportunities throughout the State. Their respective alliances with the Indian National Congress (INC) and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) have further channelled the State’s ethical politics towards national political parties hoping to make their political fortunes in it. Even as the national parties bring money and glamour to Bihar, they must bow before the ethical politics fashioned within the State by its homegrown political parties on their terms.

But what is the ethical politics in Bihar a politics of? A vibrant tradition of progressive movements and a political vocabulary of dignity layered onto the collective hum together suggest an ethical politics of hope. Hope here refers not only to an expectation-charged emotion harboured by individuals but also, perhaps more crucially, to a collective motivation to act together in times of crisis and breakdown. This motivation of acting together stems from, of course, an aim to bring about a better future but does so by foregrounding the need to persevere through the present. Put another way, hope is not “waiting for” things to be done for you but “waiting to” do things now with an eye on improving life for yourself and future generations. Biharis demonstrate the ethical politics of hope in their political and social life as they navigate economic vulnerability, social conflict and political uncertainty.

The millions of Biharis who criss-cross India in search of a dignified life bear testimony to their unwillingness to passively “wait for” things to be done for them. Their journeys to live, love, and labour beyond their home State suggests an active “waiting to” do things that would improve their lives and those of future generations. Without for a moment romanticising their precarious lives, we must respect the possibility that for many Biharis, working elsewhere offers them the chance to remit monies and ideas that help challenge caste-based discrimination back home. At the same time, they do not delude themselves into believing that their lives will simply improve by working hard. Rather, they demonstrate a realistic hope that constantly evaluates emerging opportunities, the costs these are likely to incur and being attentive to the difficulties of the present moment. Battling the prospect of electoral exclusion in the upcoming polls, several among them insist on returning home to cast their vote, forgoing their wages for the days they will be away from work. Readers will undoubtedly have met many domestic helps, security guards and vegetable vendors who will partake of Chhat festivities in cities where they work to minimise absence and then proceed home to vote. Faith matters, but franchise more so—signalling their persistent hope that their vote counts in making change.

The millions of Biharis who criss-cross India in search of a dignified life bear testimony to their unwillingness to passively “wait for” things to be done for them.

An ethical politics of hope also infuses Biharis’ attempts to navigate social conflict. As the social fabric of their State threatened to be ripped apart by ghastly communal violence in Bhagalpur during the winter of 1989, their politicians refused to let religious polarisation hold sway. Yadav and Kumar, both heirs to the socialist tradition, together with fellow-traveller Ram Vilas Paswan, stitched together a novel electoral alliance that reached out to Bihar’s beleaguered Muslims and included them in an alliance with historically oppressed communities within the Hindus. That alliance prevented nationwide Hindu-Muslim strife in the aftermath of the Babri Masjid’s demolition from spilling over into Bihar, thereby averting a bloodbath. Long after the trio parted ways, they found novel ways to maintain cross-religious alliances: Yadav’s RJD aligned Ashraf Muslims with Yadavs whereas Kumar’s JD(U) stitched together Pasmanda Muslims in alliance with Kurmis and marginalised communities from among the Dalits. Even as Kumar and Paswan aligned with the BJP, they assiduously sought to cultivate peace between the two communities, backed by the national party’s State president Sushil Modi. Paswan famously resigned from the Union Cabinet in 2002 protesting the violence against Muslims in Gujarat that year.

An ethical politics may also be discerned in the behaviour of the State’s politicians. While Indian politicians are routinely dismissed as rank opportunists who are less motivated by principle and more moved by power, Bihari politicians are especially marked out for their alleged corruption, nepotism and worse. Yadav occupies pride of place in this pantheon of the damned but politicians across the State tend to be disparaged as a whole. Such commentary neither recognises the politicians’ ethical commitments nor the subtle reasonings of their followers. Yadav’s demonisation by India’s largely Savarna media needs to be juxtaposed against the very substantial ways in which historically oppressed communities felt empowered because of his politics. His alliance with the Congress in the wake of Hindutva’s rising tide has been repeatedly condemned as hypocritical.

Kumar’s flip-flops have earned him the moniker of palturam, the master of changing sides: what is less appreciated is that he has pioneered the art of multi-alignment, a policy principle that celebrates the art of aligning opportunistically with whichever power India deems to be favourable to its interests. Ignoring Kumar as the India of Indian politics, pundits continue to erroneously hail multi-alignment as the Prime Minister’s brainchild. All Yadav and Kumar are doing amidst the thicket of Bihari politics, like India is attempting as it wades through choppy geopolitical waters, is to avoid being undermined by relatively more powerful players. Their attempts at crafting novel alliances are as much about electoral politics as about advancing an ethical politics of hope.

An ethical politics of hope goes well beyond an individual emotion to signal a collective refusal to accept the inevitability of defeat. It avoids fixating on collapse and crisis. Rather, it reflects on appreciating the ways in which people navigate and negotiate the troubles in which they find themselves. Such reflections permeate the social and political lives of Biharis, something other Indians fail miserably to understand. Perhaps we simply can’t, because of our linguistic inability to think beyond ourselves. And what we can’t understand, we taunt.

(Views expressed are personal)

Indrajit Roy (D.Phil, Oxon) is Professor of Global Development Politics at the University of York and the Author of Audacious Hope: An Archive of How Democracy is Being Saved in India as well as forthcoming Indians: A Political Biography

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

This story appeared as The 'Hum' Factor in Outlook’s November 11 issue, titled "Caste is the Biggest Political Party in Bihar," which explores how caste plays multiple interconnected roles in seat-sharing and coalition-building in the land of the setting sun.