Summary of this article

:

Upper-caste students believe that the UGC's equity regulations could be misused by SC, ST, and OBC members.

The Samajwadi Party notes that UGC protests have helped the BJP divert attention from issues such as unemployment.

Dalit, Adivasi, OBC, and minority student protesters frame the regulations as a matter of constitutional accountability.

Krishna Mohan Tiwari, a 19-year-old student of Hindi literature at Lucknow University, is known among his friends as a “reasonable man”. Tiwari who grew up in Ayodhya, is quite agitated since the University Grants Commission-issued equity regulations to counter discrimination on campus. He thinks it would create division among friends and would turn academic campuses into “caste ghettos”.

“At present we don’t talk about caste identity of our friends. We have a Yadav friend as well. Among us our caste identities don’t matter. He has never complained to us that we have discriminated against him. In fact, he calls me a pandit and jokes about my caste and I do the same. I am sure the UGC regulation will affect the frank relationship we share with each other,” Tiwari says.

He thinks the regulations provide “too much power” to Scheduled Caste, Scheduled Tribe and Other Backward Classes students who will “certainly misuse it.” He says, “Ours is a caste-ridden society already. The regulations will further divide it.”

He also thinks that OBCs will use the power the regulations provide them to blackmail upper-caste women into sleeping with them. “I can count a thousand ways in which an OBC man will misuse the equity regulations. What if an OBC student proposes to an upper-caste girl who rejects his sexual advances. Then he can blackmail her into sleeping with him. How could upper-caste parents allow this kind of exploitation?” Tiwari says the future of upper-caste students is at stake. “Their careers will be destroyed by OBC and Dalit students who are also their competitors for a job vacancy.”

National spokesperson of the Samajwadi Party and former professor at Lucknow University Sudhir Panwar, however, thinks that there are no jobs to begin with. He says the protests “seemed designed to divert Gen-Z’s attention from the real issues like unemployment”.

“The BJP has nothing to offer to the youth because there are no jobs. There might have been anger against the government over real issues like unemployment. The party is mobilising its own cadre to either oppose or support it.”

Satish Prakash, a Dalit intellectual who teaches at Meerut College says the protesting students should know that upper-caste students already have access to remedies under the UGC’s 2023 Student Grievance Redressal Regulations, which are caste, gender and religion-neutral.

Equity regulations do not exclude upper-caste students who can still report discrimination based on gender, disability, or other protected identities.

Equity regulations do not exclude upper-caste students who can still report discrimination based on gender, disability, or other protected identities. The equity regulations aim to correct systemic inequities. He says that regulations introduce two concrete enforcement mechanisms, the monitoring committee and the non-compliance clause, which were absent earlier. Their inclusion makes implementation mandatory for colleges and universities.

At universities such as Lucknow University, Banaras Hindu University, Jawaharlal Nehru University and University of Delhi, demonstrations led largely by Dalit, Adivasi, OBC and minority student groups frame the regulations as a matter of constitutional accountability rather than welfare. At Lucknow University, student groups staged sit-ins demanding the immediate constitution of Equal Opportunity Centres and Equity Committees mandated under the new rules.

Protesters argued that existing grievance redress mechanisms—introduced under the 2012 UGC guidelines—were toothless, poorly staffed and ultimately accountable to the same institutional hierarchies accused of discrimination. “The problem was never the absence of rules, but the absence of enforcement,” says a student activist at Lucknow University protest. “Equity mechanisms threaten those who have never had to answer for exclusion.” Supporters also read the backlash itself as evidence of why the regulations were needed.

One of the Bharatiya Janata Party’s major political achievements over the last decade has been to reconfigure caste politics away from explicit Mandal-style redistribution and toward a broader Hindu consolidation—where upper castes, non-dominant OBCs, and sections of Dalits could be mobilised under a shared cultural-nationalist frame. This coalition paid dividends in the last Assembly election in Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and in other states, where OBC voters who were not beneficiaries of regional social justice parties aligned with the BJP. In the 2022 UP elections particularly, non-Yadav OBC support for the BJP was instrumental in consolidating power and offsetting SP’s core support among Yadav OBCs and Muslims.

The upper-caste protests against the government over the UGC equity protests disrupt that equilibrium. And this is the reason BJP as a party is hesitating to take a stand on the issue, but given that it was Modi government issuing these regulations, has already sufficiently angered the upper caste. It seems like there are two powerful currents and in between stands the ruling party.

This has produced a rare spectacle: two social groups that have recently shared an electoral platform now confronting each other in adversarial protests, using the language of rights against one another.

For the BJP, it has become such an uncomfortable situation. The party’s caste coalition rests on strategic ambiguity: it speaks the language of social justice and OBC empowerment while simultaneously reassuring upper castes that redistribution will not threaten their institutional dominance.

And the UGC equity regulations force that ambiguity into the open. For the BJP, supporting the regulations outright risks alienating upper-caste voters and student groups who are already angry with the government and see the framework as punitive and exclusionary, while opposing or diluting them risks reinforcing the perception—already strong among OBC and Dalit activists—that the BJP’s social justice rhetoric stops short of institutional reform.

The party’s guarded response so far, and the Union education ministry’s emphasis on “no injustice will be allowed” reflect this bind.

Nirnimesh Kumar, a senior UP-based journalist says, “For the time being the Supreme Court’s stay has given the government some time, but the chasm of this vote-coalition is out in the open. The problem of the BJP is that on the one hand is the BJP’s core voter. This includes upper-caste voters which is quite influential and which has historically carried forward the party’s maximum propaganda on Hindutva. And on the other side of this conflict is the vote-base which the BJP has managed to win with great difficulty. This is the vote of over 27 smaller non-dominant OBCs (non-Yadav, non-Jat) and 15 non-dominant Dalit subcastes (non-Jatav) which the Modi government has spent last decade to win over,” he says.

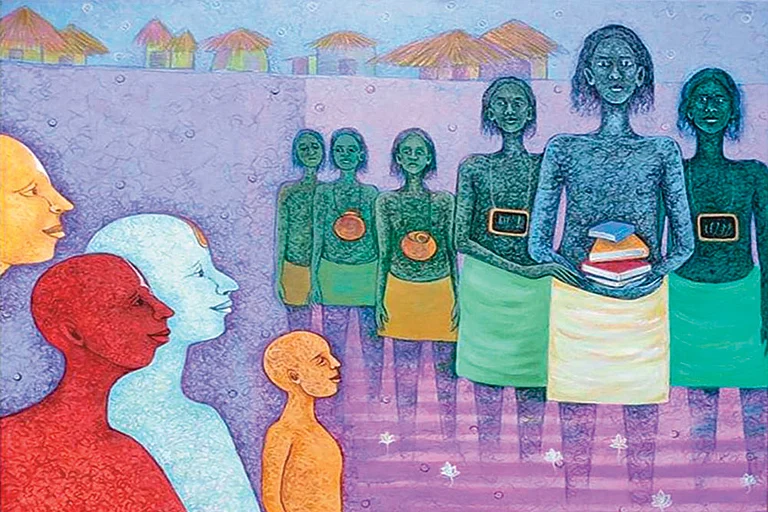

When equity moves from rhetoric to regulation, coalitions built on cultural unity begin to fray. Upper-caste protesters tend to frame the issue as one of misuse of power.

“This upper-caste anger has been simmering for quite some time now. They saw the BJP wooing OBCs at the cost of upper-caste interests of the last decade or so, but were silent all this while. The Modi government releasing these equity regulations was the trigger for a full-scale expression of upper caste anger which demands the government to take a stand,” Kumar notes. The BJP stands in between these two major voting blocs. In that sense, the protests expose pre-existing caste tensions that electoral arithmetic had temporarily papered over, Kumar adds.

What makes this episode sharper than earlier disagreements is that the conflict is no longer symbolic. Unlike debates over history syllabi or nationalism—where cultural consensus can be manufactured—the UGC regulations deal with material institutional power: complaint mechanisms, disciplinary authority and administrative accountability.

When equity moves from rhetoric to regulation, coalitions built on cultural unity begin to fray. Upper-caste protesters tend to frame the issue as one of procedural fairness and misuse of power. OBC and Dalit supporters frame it as corrective justice and delayed accountability. These are not easily reconcilable positions, and they map directly onto caste location. It is fair to say that the UGC equity protests have punctured the idea that caste contradictions within the Hindu vote have been fully resolved.

Every upper-caste supporter of the BJP Outlook spoke to expressed shock that the Modi government could take a decision against such interests of the upper castes. “It is quite shocking and just unbelievable that Modi ji would allow such a preposterous decision. Modi ji should fire Dharmendra Pradhan,” Tiwari says. It is this shock which has given way to the talk of this being a deliberate strategy.

Several political observers argue that the controversy around the UGC’s equity guidelines cannot be read as an administrative misstep or a policy surprise. Senior functionaries across the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh and the BJP are typically kept informed of major education policy decisions, particularly those with clear social and political ramifications. That has led to a more pointed question circulating in political circles: what do seasoned political strategists like Narendra Modi and Amit Shah stand to gain from a move that appears to antagonise a section of their own support base?

One possible answer, articulated by several supporters of Yogi Adityanath, is explicitly strategic. With the Uttar Pradesh Assembly elections due in 2027, they argue that the timing of the guidelines is politically loaded—late enough to disrupt caste alignments but early enough to allow for recalibration. In their reading, the visible anger among sections of upper-caste students and organisations over the equity framework risks denting a social bloc that has been central to Adityanath’s electoral dominance in the state.

“If upper-caste disaffection consolidates, it directly weakens Yogi’s base,” says a BJP leader from eastern UP, requesting anonymity. “That doesn’t automatically help the Opposition, but it complicates his path to a comfortable victory.” According to this view, even a reduced margin—or a fractured mandate—would alter the internal balance of power within the party.

These interpretations draw strength from the longer arc of the BJP’s internal politics. Adityanath is widely regarded as one of the few remaining chief ministers who retains an independent political persona and mass base beyond that of Modi and Shah. Against that backdrop, some Adityanath loyalists interpret the equity guidelines as more than a regulatory intervention. They describe them as a potential political lever—one that unsettles the upper-caste-OBC coalition that helped the BJP dominate the 2022 Uttar Pradesh Assembly elections. According to this line of thinking, once electoral damage is done, the Union government could soften or amend the guidelines, positioning itself as responsive to public sentiment while reasserting central authority.

There is no hard evidence that the guidelines were conceived with this end in mind. But the fact that such readings circulate so widely within the BJP ecosystem is itself revealing. The controversy has simultaneously exposed fault lines within the party’s caste coalition and its leadership hierarchy, turning a debate over campus equity into a proxy for deeper anxieties about control, succession and power within India’s ruling party.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

This article appeared in Outlook's February 21 issue titled Seeking Equity which brought together ground reports, analysis and commentary to examine UGC’s recent equity rules and the claims of misuse raised by privileged groups.