After the Supreme Court’s 2019 verdict and the Ram temple’s 2024 consecration, many Muslims view Ayodhya as a closed chapter, preferring calm acceptance over renewed conflict.

In contrast to the mobilisation of the 1980s and ’90s, Muslim scholars, clergy, and community leaders now emphasise keeping the Gyanvapi and Mathura disputes local and relying solely on legal processes.

Decades of failed negotiation attempts over Ayodhya—and fears that concessions would trigger fresh demands—have reinforced a preference for court-led resolutions rather than political agitation.

Following the Supreme Court verdict in 2019 and subsequent Pran Prathisha in 2024, Muslims in India have accepted the reality of Ram temple in Ayodhya bringing in a sense of closure.

All eyes are now on court proceedings relating to Gyanvapi and Mathura disputes. The dominant view among the country’s largest minority community is to keep row localised and resort to legal recourse. So

unlike the 1980s, Babri action committee and political agitations that were led by Syed Shahabuddin, Zafaryab Jeelani etc, Muslim intelligentsia, clergy and community leaders are dismissive about

making Kashi-Mathura disputes political or nationwide.

For over three decades, there were two shades of opinion over Ramjanambhoomi-Babri masjid dispute. A section of Muslims, largely politically inclined and clergy, had vetoed any prospects of a “compromise” before or after the Supreme Court, There were Islamic scholars like Maulana Salman Nadwi of Lucknow’s renowned Islamic Nadwa seminary who had favoured shifting of mosque (where Babri masjid fell on December 6, 1992) to another spot within or away from Ayodhya.

To support his line of argument, Maulana Nadwi had cited the example of Caliph Umar Bin Khattab when he had shifted a masjid of Kufa (present day Iraq) to another place and established a market of dates on the place of masjid. Maulana Nadwi , who is now considered as 'controversial' , had also referred to the treaty of Hudaibiyah, a peace accord, signed by Prophet Mohammad in 628 CE. Even Though some points of the treaty were not favouring Muslims, overall, the agreement turned out to be a good thing for the followers of Prophet Muhammad because the treaty, subsequently benefited the Muslims in several ways.

Maulana Nadwi’s call to avoid conflict and clash has, however, not gone down well with many Muslim community leaders. It saw Nadwi’s summary expulsion from All India Muslim Personal Law Board (AIMPLB), an informal but influential body of various Muslim sects in India.

At that point of time, many Muslim scholars, retired bureaucrats, members of judiciary and those well versed in politics, had argued that a compromise or a “goodwill” gesture would not suffice. They had

said that such a course would open floodgates of similar concessions from Muslims for other places of worship including Krishna Janambhoomi-Idgah dispute at Mathura and Kashi Vishwanath temple-Gyanvyapi mosque in Varanasi. It may be pertinent to note that when Ram Janmabhoomi agitation in Ayodhya was at its peak sometime during 1988-89, a group of VHP , with promptings from the RSS were demanding a change in the Constitution.

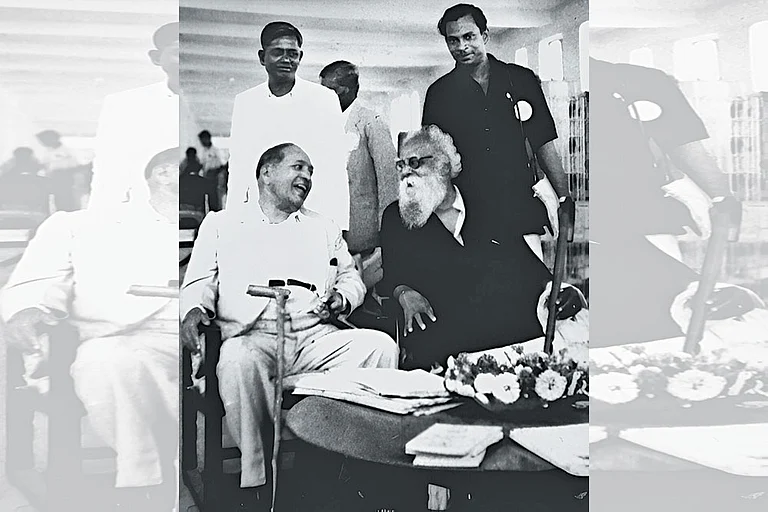

Noted author-journalist Arun Shourie’s work “What happened to the Hindu temples” [during Muslim rule in India] listed out a list of some 3000 mosques which he claimed were built on erstwhile temples. In private conversation, Syed Shahabuddin, former foreign service officer turned politician-parliamentarian used to say that he often toyed with the idea of making some sort of unilateral goodwill gesture in Ayodhya dispute but backed out fearing that the demand may go on for Mathura, Kashi and 3,000 other places of Muslim worship.

The closure, through a Supreme Court verdict, was preferable on many counts. A compromise, as a jurist at that point of time had argued, no matter how 'favourable' the terms and conditions of such a

compromise would have been, the individuals signing the 'compromise' would have been accused of ‘selling’ the interests of Muslims for cheap. The recrimination would have grown with time. In contrast,

adverse ruling from the apex court brought a sense of 'closure.'

Incidentally, there were nine attempts to solve the Ayodhya dispute through negotiations and compromise since 1859. [in 1859 communal clashes over the possession of the site had taken place prompting the then British administration to erect a fence: The inner court was to be used by Muslims and the outer court by the Hindus]

Three serious attempts during Chandrashekhar, P.V. Narasimha Rao and Atal Bihari Vajpayee regimes when Muslims came tantalizingly close to an “out of court” settlement to resolve Ayodhya dispute.

In 1990, Prime minister Chandrashekhar tried to resolve the dispute through negotiations bringing both VHP and Muslim historians on the negotiation table but volunteers of the Vishwa Hindu Parishad damaged the 16th century mosque in Ayodhya bringing an abrupt end to talks.

Before Babri mosque was demolished, Prime Minister Narasimha Rao made attempts to dissuade the VHP from launching a movement. In his 317-page book “Ayodhya 6 December 1992” (Penguin/Viking 2006) , Rao made a singular point --- BJP aborted the Ayodhya solution. Always careful with words, the late Prime Minister insisted that BJP scuppered a possible solution to the temple dispute to keep the Ayodhya pot boiling. Till August 1992, Rao says, his talks with “apolitical” sadhus and sanyasis on how and where a Ram temple could be built in Ayodhya ' without breaking the law or upsetting communal harmony ' were proceeding quite well. Then, all of a sudden, the sadhus broke off the talks. “Why did they (the sadhus) go back on their promise (to explore all avenues towards a peaceful settlement of the dispute)'” Rao wondered and then offered an explanation, “It was clear that there was a change of mind on their (the sadhus’) part or, what is more likely, on the part of political forces that controlled them.

In 2003, an upbeat All India Muslim Personal Law Board in Lucknow had summoned its grand assembly to clinch the Babri Masjid issue on the premise that the Vajpayee regime and the Sankaracharya of Kanchi would prevail upon the VHP to accept the legal mandate on the Ayodhya dispute. Vajpayee was prime minister and everything looked ‘final’ when a last minute spanner deprived him from going down in history as the greatest Indian.

The AIMPLB had given its final touches to a proposal to be made to Sri Jayendra Saraswati that had sought a mosque within the 67 acres of undisputed land, a legal mandate to debar Hindutva forces from raking up Mathura and Kashi, and a plaque at the disputed site recording the chronology of the dispute.

The moderates in the otherwise hawkish AIMPLB had got a shot in the arm when the influential Nadwa theological school decided to back the board’s bid to hammer out a compromise. Maulana Rabey Nadwi, rector of Darul-Uloom Nadwa, said there was no harm in a negotiated settlement.

The Muslim Personal Law Board had invited all Muslim MPs and community leaders to thrash out the Ayodhya issue.

However, Vajpayee and Kanchi Sankaracharya’s efforts to end the Ayodhya dispute were criticised by the VHP and RSS. It was a make-or-break gamble for Vajpayee who was keen to find a permanent

solution to end the Ayodhya impasse as it was unwilling to give a piece of land for a new Babri masjid near the disputed site.