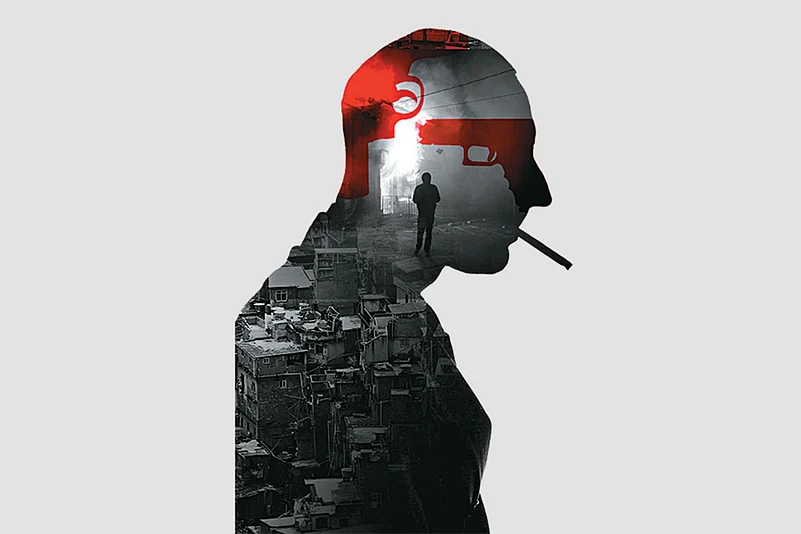

Operation Containment in Rio’s favelas, particularly Complexo do Alemão and Penha, led to at least 121 deaths—many allegedly without warrants—raising serious concerns of extrajudicial killings and state violence against impoverished communities.

Favelas remain abandoned by public institutions, leaving residents to navigate a landscape shaped by poverty, crime, and limited social support, where cultural expressions and everyday resilience coexist with high homicide rates and constant danger.

The crackdown mirrors global patterns, with leaders like Rodrigo Duterte and Nayib Bukele using violent anti-drug campaigns that disproportionately target the poor, eroding due process and human rights under the guise of restoring order.

Several years ago, I visited Complexo da Penha in Rio de Janeiro while doing a story on the favelas (slums) and crime. I was struck by the labyrinthine alleyways along which perched makeshift homes on steep slopes, a favela geography that made bare life difficult. Beside one of these homes, I found a mango tree and focused on it to give me a sense of hope and possibility amidst what seemed to be utter desolation. The mango tree was brought to Brazil from Asia by the Portuguese not long after they began to colonise this vast and beautiful land.

When I pointed out the tree to my friends who accompanied me to Penha, they introduced me to a fantastic Brazilian expression, O cão chupando manga. The expression literally means ‘the dog or devil sucking on the mango’, but, in fact, it refers to someone or something that is ugly, or it refers to a person who had great skill or who is doing something very difficult. When I read about the police assault on Penha in October 2025, I thought about that mango tree and remembered the expression.

On October 28, about 2,500 police officers entered two favelas in Rio de Janeiro—Complexo do Alemão and Complexo da Penha—and began to arrest and execute people whom the State had accused of being involved in the drug trade. The entire raid went by the name of Operation Containment (Operação Contenção), and it was to target the Red Commando (Comando Vermelho) criminal organisation.

These favelas, in Rio’s North Zone, are densely populated, scarred by poverty and scarce public services. The police officers extinguished 121 lives, not numbers for their families but worlds. Of note, the leader of Comando Vermelho—Edgar Alves de Andrade (known as Doca)—was not arrested or killed. One mid-level member of the gang surrendered without a gun being fired.

In some of these places, the gangs provide the services that the State once provided.

The number—121—is the official figure, but it is likely that the number will be higher. For now, the government is not releasing a list of names of people who have been killed, but families of the dead say that there is an enormous discrepancy between those who have been killed and those for whom there were arrest warrants (some people say that none of those killed had arrest warrants). If that is true, then the Brazilian police killed innocent people. To call this the October 28 Massacre might be appropriate.

The attack on Penha and Alemão was ugly. But it is also wrapped up in a terrible problem. There are drug gangs in these neighbourhoods, and they do wreak havoc for the families who see their children preyed upon. But the gangs are not the problem. They are a symptom of a much deeper problem.

Places like Penha are pickled in a combination of ordinary hope amongst very poor people and the cultural desolation of their surroundings. State institutions have abandoned these impoverished neighbourhoods, non-governmental organisations exist only on the margins and are deeply underfunded, and trade unions no longer have the number of members to sustain cultural organisations such as union halls and community centres.

Instead, the main social groups are the Pentecostal churches and the drug gangs, with an occasional outpost to dance the Samba (escolas de samba) and to practice capoeira (Brazilian martial arts). Some favelas still have associations for residents (Associações de Moradores), although these are often dormant. When we walked through Penha, we met some people from one of the Bloco Carnavalesco (carnival groups) from the neighbourhood and visited a studio where we watched a roda (round) where young men and women practiced capoeira. There is beauty in places where the working class struggles to build social lives amidst so little. But there is also danger.

The annual homicide rate across Brazil is 17.9 per 100,000, but in favelas such as Alemão and Penha, and in Jacarezinho and Cidade de Deus it is 34 per 100,000—twice the number. The favela Cidade de Deus was used in the Brazilian film of the same name in 2002. Those who have seen the film will remember the moment when Buscapé (Rocket) says, “In the City of God, if you run, the beast catches you; if you stay, the beast eats you” (Na Cidade de Deus, se corer o bicho pega; se ficar o bicho come). It is a horrific sense of the impossible choices that young people face in Brazil’s favelas. Either young men such as Buscapé join the drug gangs and make a little money and get shot, or they do not join them and get killed in the crossfire—either way they die young. One cannot romanticise these neighbourhoods, which have become more and more dangerous for young people.

And there lies the challenge.

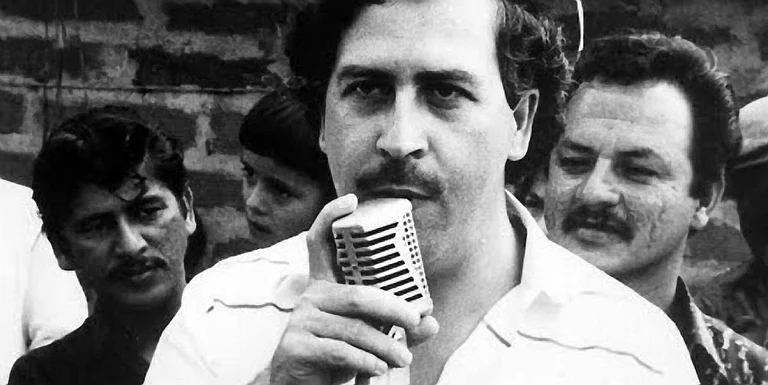

In the Philippines, Rodrigo Duterte, before he became president was the mayor of Davao City in Mindanao. Duterte would go to rallies carrying a gun and say that the only way to deal with drug dealers was to kill them.

For this, Duterte built his popularity and won elections on the pledge to clean up the city and then the country. He is now charged in the International Criminal Court for killing of 19 people while he was mayor, and then with the killing of 14 people while he was president.

There is an accusation that thousands of people were killed under his watch in his ‘War on Drugs’.

Meanwhile, President Nayib Bukele in El Salvador is celebrated for exactly this same strategy of using extreme violence against poor communities where drug dealers work and live. In these places, men such as Duterte and Bukele have made the war on crime a war on the poor.

Governments claim that they are trying to bring order, yet the cost is borne by those with the least protection—youths swept up in mass arrests, alleged dealers executed without trial, families left without answers. Fear becomes policy; impunity, its companion. Streets appear calmer, but beneath the surface lie unmarked graves of due process, accountability, and human dignity. These killings echo each other across borders: a grim chorus reminding us that security without justice is merely violence wearing the mask of authority.

And yet, the question remains.

What does one do with the gangs that certainly terrorise the neighbourhoods of the poor? It was the drug trade, facilitated by drug mafias and consumers in the Global North, which enhanced the power of these gangs. But it was the total neglect of these neighbourhoods —which lost their local schools and their local healthcare facilities and their local police officers—that allowed the gangs to root themselves. In some of these places, the gangs provide the services that the State once provided, and so the gangs have integrated themselves into society.

I was naïve to be surprised when a boy told us that their uniforms for the carnival had been sponsored by a gang. That had become something quite ordinary. It is not enough to complain about the killing of 121 people. People in Alemão and Penha are agitated and afraid. But what comes next? Another police raid or engineers and cultural workers to improve the neighbourhood? The State returns to these neighbourhoods, but not to provide education or healthcare or even uniforms for the carnival: the State returns as a killer.

It was mango season in Brazil. I imagine that tree in Penha laden with mangoes as the police rush by, their guns aflame, the bullets marking the trunk of the mango tree. I imagine one of the bullets going through a mango, making an opening for the mosca das frutas (fruit flies); what was made by a bullet has become a home for a little animal.

(Views expressed are personal)

Vijay Prashad is the director of Tricontinental: Institute For Social Research. His latest book is on Cuba: reflections on 70 years of revolution and struggle, written with Noam Chomsky

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

This story appeared as When The State Is The Killer in Outlook’s December 11 issue, Dravida, which .captures these tensions that shape the state at this crossroads as it chronicles the past and future of Dravidian politics in the state.