In late 2014, I was taken to see the Gaza War Cemetery in al-Tuffah (The Apple) by my new friends Yasser Murtaja and Roshdi Sarraj of Ain Media. They wanted to show me the Indian graves in this old British cemetery. We met the caretaker there, Essam Jaradah, who took us to see the Indian section. Soldiers from across the British Empire had been brought here to fight the Ottoman troops during the First World War.

I had not expected to see these graves in Gaza. I knew that Indian soldiers had fought in Basra (Iraq) because some distant relatives of mine had been part of the misnamed British Expeditionary Force. The British named their armies in such a way that one could assume that the soldiers were from some small towns in England, but they were not. They were largely from India and Egypt. The 7th Meerut Division and the 3rd Lahore Division made up the troops, while the Indian Labour Corps and the Camel Transport Corps formed the logistical backbone of the British forces in Gaza. The dead in the cemetery came from them, and it was their names that I traced on the stones, and it was these soldiers who made up the dead in the unmarked graves.

Murtaja, who was curious about the graves, asked me about the presence of the Indian soldiers. All I could tell him was that they would have been like my ancestors, who fought in so many wars for the British Empire (including in the Second World War in Europe itself). But it was only later that I read about the Indian soldiers who fought under General Edmund Allenby in his confusingly named Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EFF) in 1917. The British commanders wanted to weaken the German-Ottoman forces by breaking through the Ottoman lines and taking Jerusalem. But the defences in Gaza prevented them twice.

So, Allenby decided to use his EFF to seize Beersheba, southeast of Gaza, and then pivot his cavalry to ride around the Ottoman defences. It was said that the Ottoman defences had ‘a gun concentration equivalent to that of July 1, 1916 on the Somme’, in other words, ferocious. The Desert Mounted Corps, with Indians at the helm, put on their bayonets and rode through the Ottoman defenders. They then turned to Gaza and seized Tell Ali Muntar—the archaeological dig at the Bronze Age settlement in this town had not been damaged till the Israeli bombing of Gaza in 2023. Within two weeks, the Indian troops led by Allenby defeated the Ottomans and captured Jerusalem.

The graveyard was peaceful that afternoon; a few families were sitting on the grass enjoying the sunshine. Jaradah told us that his family had worked for the Imperial War Graves Commission since 1923, when his grandfather, Ibrahim, started to work for them in Beersheba—the site of Allenby’s first triumph. Murtaja and Sarraj, both enthusiastic photographers, took some pictures.

They had sent them to me, but I can’t seem to find them, and it is impossible to ask them to send it again: Murtaja was killed on April 7, 2018, when he was covering a Palestinian protest near Khan Yunis, and Sarraj was killed by an Israeli airstrike on his home on October 22, 2023. I was interested in the graves of the Indian soldiers, many of their markings degraded by Israeli missile strikes. I have not been able to reach Jaradah or his son Essam, who now tends these graves, but news reports suggest that the Israelis have struck the graves again during this ongoing genocide. Even the dead are not safe.

When Israel Almost Killed Nehru

A decade before this visit to the graveyard, I had sat down with General Indar Jit Rikhye and Cynthia de Haan Rikhye in their home in Charlottesville, Virginia. I had come to talk to them about the late days of their vigil in Gaza when General Rikhye commanded the United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF) with Cynthia de Haan as his secretary. General Rikhye had many colourful stories to tell. In 1946, his superiors had written a poor report for his lieutenant, Zia ul-Haq, but Rikhye had countermanded the order to dismiss him; when I met Rikhye, he said he should perhaps have accepted their judgement as Zia would later lead Pakistani troops against the Palestinians in Jordan in 1970 and then become the dictator in Pakistan from 1977 to 1988.

Dismayed by the violence of Partition in 1947-48, Rikhye requested for a transfer to become a peacekeeper with the United Nations. That is precisely what he did for the remainder of his military career, before he took over as the president of the International Peace Academy. Rikhye was intermittently in Gaza from the late 1950s between posts in the Congo and at United Nations headquarters. In 1966, Rikhye took command of the UNEF and the following year, when the UN peacekeepers were forced out of Gaza, he was the last man at the post, a ‘commander without troops’, he said with a smile. Along with Cynthia and his aide (a Brazilian officer, Captain Carlos de Silvera), their Canadian UN driver took them from Gaza to Beirut. This was an exciting story.

What we are now witnessing was always going to be the inevitable consequence of livestreaming and virtual participation of the public.

That day in Virginia, however, he told me another story. In 1960, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru came to Gaza from a Commonwealth Prime Ministers’ Conference in London. He came to visit the Indian soldiers and was taken to see the graves of Indian soldiers. Nehru was in good spirits because he had joined Malaysia’s motion in the Commonwealth meeting to condemn it for its support of apartheid South Africa.

Nehru met the troops, ate with the Indian commanders, visited the graveyard, and then boarded the UN aircraft to fly him to Beirut. As the UN aircraft took flight, two Israeli fighter jets appeared and came along both sides of it. They began manoeuvres to force the UN plane to either land or crash. Nehru watched from the window. He could see them come closer to the UN plane and harass it. The UN pilot was unfazed. He had experience with this sort of thing. The plane was able to extricate itself and Nehru went on his way to Beirut. He did not say anything while he was in Lebanon. On August 1, 1960, in the Lok Sabha, Nehru said that the Israelis had been informed about his trip to Gaza and knew that he was on a UN aircraft. The Israeli actions, he said, were ‘unwarranted’. Israel did not apologise at that time and has not apologised to this day.

Silence is a Form of Complicity

When I returned from Gaza in 2014 to Delhi, I went to see a friend who was then in the Ministry of External Affairs. I told him this story about Nehru and asked why India—which had once been the closest ally of the Palestinians—had now befriended Israel and almost forgotten about the plight of the Palestinians. He was frank. When the Soviet Union collapsed in December 1991, India began a process to improve relations with the US. The US government clearly told the Indian officials that the price of admission to the good graces of the US was to normalise relations with Israel. The road to Washington, they were told, had to go through Tel Aviv. In January 1992, therefore, India opened its embassy in Tel Aviv, and Israel did the same in New Delhi.

His shift happened very fast. Then, when India tested nuclear weapons in 1998 for the second time, India found that it could no longer import certain weapons from the US (because of the Glenn Amendment of 1977 and the Solarz Amendment of 1985 that sanctions countries that test nuclear weapons); India began to import US grade weapons from Israel. In 2003, Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon visited India, and then in 2017, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi went to Tel Aviv. Where once Indira Gandhi walked onto the tarmac to welcome Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat to India, and where he called her his sister, now Modi was in Israel after the ferocious Israeli bombardment of Gaza in 2014, silent on the death of the 3,000 Palestinian civilians, many of whose homes I visited.

It was a miserable feeling. I had written a book called Namaste Sharon (LeftWord, 2003) that analysed this shift, but it still did not sit well with me. The cynicism of India’s foreign policy turn bothered me as I thought about Nehru in his UN plane and the Indians who died on that soil, and of General Rikhye trying to keep the peace. As this genocide has unfolded, Modi has not brought himself to condemn it. In June 2025, the Indian government walked away from a simple statement made by the Shanghai Cooperation Organization that condemned Israel for its illegal attack on Iran (a fellow BRICS and SCO member). What is there to say, words being easy but actions being more powerful? I suppose the slogan, silence is a form of complicity, is enough.

Murtaja and Sarraj, my companions to the graveyard, are dead. Sarraj was killed by an Israeli airstrike while eating breakfast in his home. His wife, Shrouq Al Aila, and his baby daughter survived. Shrouq Al Aila is now the head of Ain Media and won the International Press Freedom Award in 2024.

I am surrounded by ghosts. They are not silent. They ask us to speak for them.

(Views expressed are personal)

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Vijay Prashad is the director of Tricontinental: Institute For Social Research. his latest book is on Cuba: Reflections On 70 Years Of Revolution And Struggle, written with Noam Chomsky.

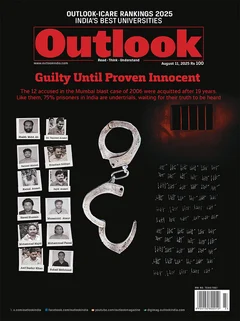

Outlook Magazine’s next issue, “Guilty Until Proven Innocent”, looks at the 19 years lost of those who were in jail and those who thought justice was served, until it wasn’t. This article appears as 'The Ghosts Are Not Silent' in the magazine