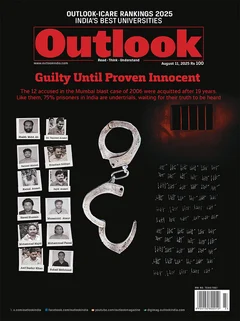

On July 11, 2006, seven bombs tore through Mumbai’s local trains, killing 189 people and injuring over 800. In the months that followed, the police announced that it had cracked the case. Twelve of the arrested men were tried and later convicted. Five were sentenced to death.

Last week—almost two decades later—the Bombay High Court acquitted them all. The judges ruled that the evidence against them was unreliable, contradictory and, in many cases, fabricated. At that moment, justice stood exposed—not because it had been delivered, but because it had long been denied.

What happens when law enforcement responds not to facts, but public opinion, the so-called ‘collective conscience’, as the police see it? What happens when the police attempt to satisfy the demand for retribution, rather than rely on evidence? The answer is stolen lives, buried truths and perpetrators walking free.

“The conviction of an innocent man is an insurance policy for the guilty person that now he will never be caught,” says advocate Yug Mohit Chaudhry, who along with his colleagues, Payoshi Roy and Siddhartha Sharma, represented some of the men acquitted by the court in the Mumbai blasts case. “The police closed this case not because they found the true culprits, but because they didn’t want to admit they didn’t know who the perpetrators were.”

In an ordinary murder case, a high court can—often does—acquit an accused if the evidence doesn’t hold up. It might be based on benefit of doubt or reassessment of witness credibility or technical reasons. But in terrorism cases, an acquittal wouldn’t just hinge on doubt: it would require moral and legal conviction in the unquestioned innocence of the accused.

According to Chaudhry, the Maharashtra Police’s Anti-Terrorist Squad (ATS) had no leads after the blasts. What followed was a familiar ritual: “They rounded up the usual suspects. They presumed it was a case of Islamic terrorism. They decided SIMI [Student Islamic Movement of India] was a banned outfit and its members were behind it. They made up a theory, stitched it together with confessions under duress and called it a solved case.”

One of the most damning aspects of the case was the deliberate suppression—and eventual destruction—of evidence of the innocence of the accused. “They claimed these men were conspiring over the phone with Lashkar operatives,” Chaudhry says. “We demanded their call data records [CDRs] to show their location during the alleged conversations. They refused it to us six times. Finally, the High Court told them to hand it over. Next thing we hear? The CDRs have been destroyed.”

This wasn’t just negligence. It was sabotage. And ultimately it led to the acquittal.

It’s tempting to imagine this case as a one-off instance of justice miscarried. But the truth is far more chilling. Experts say India’s policing and judicial system are routinely shaped by media frenzy, political pressure and social prejudice, especially in cases involving terrorism, caste or communitarian violence. Senior Supreme Court lawyer Kirti Singh says, “The police are not clueless about how to gather evidence. They deliberately ignore it or are very careless. They play to the gallery or act under orders from above.” This fuels the popular belief that the police are not impartial when they investigate and are amenable to influence or corruption in non-political cases. “They act like highly socially conservative forces and tend to side with communal or casteist forces because they get swayed by these forces or are asked not to intervene,” Singh says.

Faizan Mustafa, a renowned constitutional law expert, offers a diagnosis of the systemic failures that plague many investigations. “The police often don’t want to investigate,” he says. “When unable to gather solid evidence, they often resort to arresting anyone rather than following due process.”

Basic procedural steps, like the Test Identification Parade, in which witnesses can identify the accused, are overlooked. Numerous other flaws compound the issue. And whenever the convicted stand exonerated, the question remains, as in Mumbai: who killed or injured a thousand people?

Dr Shamim Meghani Modi, an activist and professor at Tata Institute of Social Sciences, says that India’s policing system protects nobody—not the victim, certainly not the accused. She notes, “Once you’re accused, the trial becomes irrelevant. You’re socially convicted, destroying your life before any judge speaks.”

The men now exonerated in the Mumbai bomb blasts case spent nearly two decades behind bars. Their children grew up in the shadow of ostracism. And the victims and survivors of the blasts? They, too, were failed—this is institutional failure. As the Bombay High Court notes: “...creating a false appearance of having solved a case…gives a misleading sense of resolution. This deceptive closure undermines public trust and falsely reassures society, while in reality, the true threat remains at large.”

Dr Modi, who also trains police personnel in restorative justice, has fought to reform the system—and been jailed by it.

“I’ve had cases filed against me based on fabricated X-rays. I’ve seen the police arrest someone’s innocent brother just to pressure the real suspect,” she says. “They say knowledge of the law makes good citizens. But nobody knows the law better than the police, who just ignore it.” In 2008, she was assaulted, her throat slit, but the case of attempted murder is stuck in the courts. She says, “My case is still stuck, but if it was something to do with [a] Hindu-Muslim [dispute], action would immediately have been taken.”

Her words echo an uncomfortable truth: the Indian police force remains a largely colonial institution, trained to obey, not protect rights. “The situation suits those in power. The ability to arrest and convict are tools of control.” Of course, not all police are ‘bad’. But if the state rewards obedience and punishes integrity, what justice will a system deliver?

In case after case, a pattern emerges: when police investigations stall, ‘witnesses’ surface—often months after the incident, their stories aligning suspiciously well with the police theory, rarely with independent facts. This isn’t justice unfolding but a narrative engineered to fit public and political expectations—and the pattern isn’t new. In June 2023, two Karkardooma Courts examining the Delhi violence cases of 2020 acquitted four Muslim men for lack of evidence and “shoddy” police investigations. In November 2023, a different judge acquitted seven others as the sole prosecution witness gave contradictory statements—including the incorrect date for the incident he claimed to have witnessed. Another eleven were similarly acquitted in May 2025.

Such “grave miscarriage of justice” continues as the careers of the officers who blamed innocents don’t suffer, and the cost is staggering: decades lost, a public losing faith in the law and a dangerous idea taking root that justice must reflect public beliefs rather than evidence. Dr Modi says, “We are consumed by retribution. Someone must suffer. It doesn’t matter who.” But justice isn’t about suffering. It’s about truth. And truth—when delayed—can become unreachable.

Chaudhry believes there’s a way forward: an independent commission of inquiry to identify both the lapses in investigation and the real perpetrators of the Mumbai train blasts. “Not just review but examine the entire investigation with independent persons at the helm,” he says.

For example, how is it that the police in Delhi, Mumbai, Hyderabad and elsewhere blame the Indian Mujahideen for the same blasts? In 2008, even the Crime Branch, Mumbai Police, said so. Till today, the top terrorism investigation agency, NIA, on its website, says the Indian Mujahideen committed the train bomb blasts of 2006. Are they all wrong and is only the ATS right? That’s why, Chaudhry says, the inquiry commission should be led by independent people whose integrity is beyond reproach.

What India needs is not revenge or quick closures but the courage to reopen what’s buried and admit what’s amiss—that much, in the name of justice.

Outlook Magazine’s next issue, “Guilty Until Proven Innocent”, looks at the 19 years lost of those who were in jail and those who thought justice was served, until it wasn’t. This article appears as, 'Stolen Lives, Buried Truths' in the magazine.