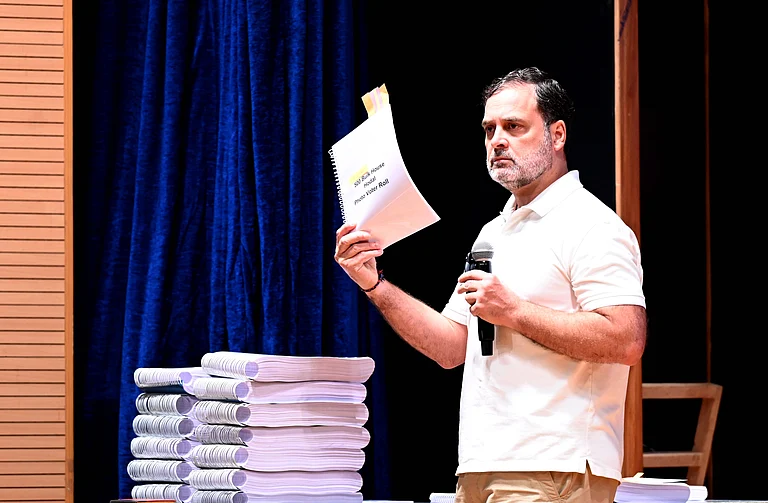

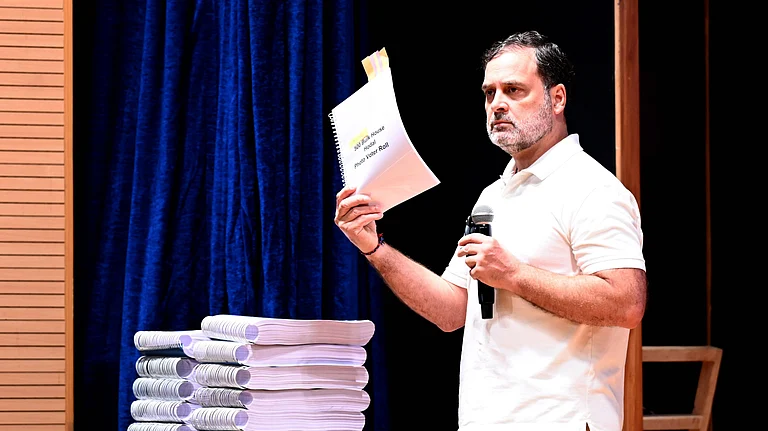

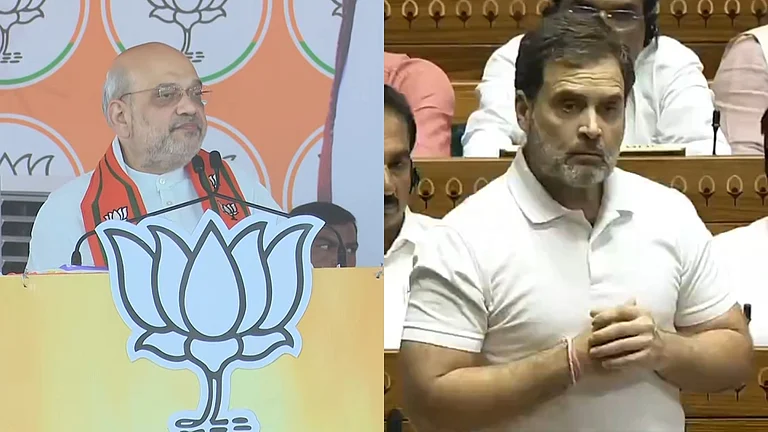

The Bihar Special Intensive Revision (SIR) has propelled India’s electoral machinery into the spotlight all over again. Officially, the exercise is meant to clean up the voter rolls, ensuring that every vote is verified. In practice, it has sparked anxiety—nearly 65 lakh voters might end up excluded for lack of documentation. The exercise is being painted by the Opposition, led in Bihar by the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) and its ally, the Congress, as a form of corruption—vote chori. It cannot but remind one of the “chowkidar chor hai” campaign launched by Congress leader Rahul Gandhi in his 2019 election campaign. But that had fizzled out—or at least not granted Gandhi’s party the victory he had hoped for by riding on an issue as emotive as corruption in defence deals.

Even in earlier high-profile campaigns—such as the Aam Aadmi Party’s rise in Delhi thanks to the India Against Corruption (IAC) movement in 2013—slogans captured attention but struggled to translate outrage into lasting change. So, will the vote chori slogan stick? After all, anti-corruption slogans in India have a longer history of sputtering out than enduring.

One difference between then and now is that vote chori is not about the familiar “note for vote” politics, where money and liquor are known to purchase voter loyalty for a day—or five years. The SIR itself is a more existential exercise, for it redefines who belongs. Further, if buying votes is a transaction, excluding voters amounts to erasure.

In this context, Vasanti Rao, Director General of the Centre for Media Studies based in Delhi, says we need to expand the understanding of corruption in India. She recounts a corporate friend telling her that corruption can include deliberately obstructing work in an office, drawing a salary without working, or simply failing to ensure accountability. All of these erode trust and efficiency in public and private spaces. But they are rarely accounted for in India, since the focus of the discourse on corruption tends to zero in on who stole what rather than the exclusions that are equally, or more harmful, but form a part of life.

So, will vote chori be like other slogans, growing faint in hindsight, until forgotten? Will the current cries of vote chori in Bihar struggle to pierce through the din of temple inaugurations, cricket victories and manufactured controversies? “Even if the entire Opposition brings up vote chori, it will not likely sustain beyond a year or two,” predicts Sandeep Suresh, an expert on electoral law who teaches at Jindal Global Law University in Sonipat. He says deeper structural issues, that few look to overhaul, lead to occasional waves of attention on corruption, only to be forgotten once the moment has passed.

For instance, he says, citizens are less attentive to the underlying power dynamics that shape their rights and entitlements. So, an energetic campaign led to the enactment of a Right to Information law, but it was eventually watered down. “RTI could seek accountability and transparency, become a bulwark against corruption, for society found the law weak and prompted it to buck up,” he says. “But over the years, the RTI law has become weak with rules amending its functionality, and it has gone unchecked by society, or underestimated by the public.”

Take the Puttaswamy privacy judgement of the Supreme Court in 2017—the new Digital Data Protection Act only institutionalised the weakening of the RTI law, by removing it from the purview of exclusions.

Consider the ongoing debate around the Election Commission refusing to share CCTV footage of voters at polling booths—it defends the denial on grounds of citizen’s privacy, when actually the right of a citizen to vote is at greater risk. “Privacy has become a counterproductive tool, used against citizens in the name of protecting them,” Suresh says.

He also highlights the Jan Vishwas Bill, 2023, which decriminalises “minor” offences across laws, one of them in the critical Drugs and Cosmetics Act, first passed in 1940. It once imposed imprisonment and heavy fines for manufacturing non-standard quality (NSQ) drugs, but that offence has been made compoundable—effectively revoking culpability for drugs that don’t meet the fixed standards. “How many citizens can connect such a watering down of liability with broader patterns of political funding? We no longer have a media that draws public attention to potential quid pro quo such as what the pharmaceutical companies contributed to parties across the board through electoral bonds,” says Suresh. When that doesn’t happen, structural manipulations rarely provoke sustained public debate.

The Bihar SIR is not just about “stealing votes”; it is about how structural mechanisms can quietly disenfranchise citizens while appearing neutral, even essential. As Rao notes, Indian politics has moved ahead from the days of “chowkidar chor hai”, but not in the necessary direction. Today, we are often bombarded with public campaigns that celebrate progress, like the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan or the Ujjwala gas scheme.

“But nobody evaluates whether they’re actually working or not. We see a politics of claiming progress but there’s no assessment or evaluation of those schemes. That is a kind of corruption too—of misrepresenting or side-stepping outcomes, making actual progress unknown,” she says. “Then we move from one controversy after the next, without letting people realise that the biggest beneficiaries of corruption are political parties themselves,” she adds.

Take another instance: Today, NGOs are scrutinised, regulated, blocked from foreign funds, all in the name of securing public interest. Parties, by contrast, operate with near-complete opacity—electoral bonds being only one instance of this—and the SIR a new form of it.

The reason slogans die out is that corruption does not touch every citizen equally. Bribery at a police station enrages individuals but rarely becomes a collective cause unless politics forces accountability. Then, even ‘cash for votes’ is cynically regarded as all too familiar. But vote manipulation, by contrast, is abstract—until it hurts the very sense of belonging that people feel with national life, nothing might change.

In that sense, chowkidar chor hai didn’t exactly backfire, nor lead to lasting change, despite being a high-profile allegation. Because in India, controversies come and go so rapidly with the inauguration of a temple or a highway, or a small scandal or even an election. Even the boldest anti-corruption campaign would struggle to sustain public attention.

Who knows this better than Kafeel Khan, the doctor-turned-activist whose fight against corruption has cost him dearly? “The public has a short memory. People rally around a cause, but another issue takes over, making them forget the fight,” he says. Yet, despite ongoing legal battles and professional setbacks, Khan remains driven, inspired by the public support that gave him courage and conviction to fight for justice. “I’m not alone, and not the only one to fight for a better country. I have been luckier than many others who languish in jail for years,” he says.

While covering the SIR exercise in Bihar, we met people grappling with the verification process. There were elderly voters, unsure which papers are valid, to families scrambling to gather documents. Even ordinary law-abiding citizens faced massive obstacles. Most of those left behind will be the poorest. Is this chori, or simply a check on rights?

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Pragya Singh is Senior Assistant Editor, Outlook. She is based in Delhi.

Democracy is about ballots, but also about memory—who safeguards both, and who seeks to rewrite them? Outlook’s September 11, 2025 issue probes these erasures—of voters, voices, and histories—asking what they mean for India’s democratic future. The article appeared in print as 'Politics of Slogans'.