On July 28, the Supreme Court reminded the Election Commission that electoral roll revisions in poll-bound Bihar should ensure “mass inclusion,” not “en masse exclusion.”

The onus of proving citizenship, an essential part of electoral rights, lies on the electors, and not the ECI, the poll panel told India’s top court in july.

Since 2019, Opposition parties have often clashed with the ECI over alleged partisan handling of Model Code of Conduct violations by ruling and Opposition leaders.

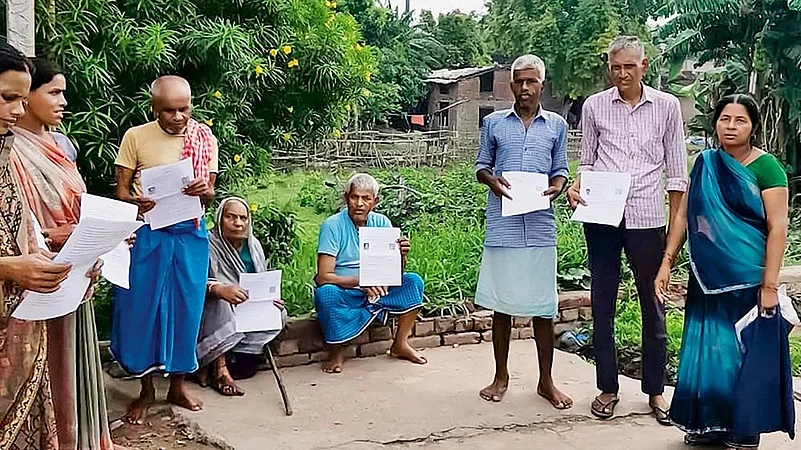

For years, among the usual visuals and news reports emerging during election time in India have been that of polling personnel travelling to remote areas—taking country boats to islands, climbing hills, crossing streams and traversing forests. The mission: to ensure even the last person is included in the democratic process.

It is then rather strange that the Supreme Court of India, on July 28, had to remind the Election Commission of India (ECI) that “mass inclusion” and not “en masse exclusion” should be the outcome of the electoral roll revision exercise in the poll-bound state of Bihar.

Three days later, the ECI’s publication of the draft voter list as part of the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) revealed as many as 65 lakh names have been removed from the voter list—setting an example of the removal of the highest number of voters in one go in the history of India’s electoral roll revision.

From making it the poll panel’s responsibility to reach out to voters, the ECI appears to have suddenly changed the rules of their engagement. The onus of proving citizenship, an essential part of electoral rights, lies on the electors, and not the ECI, the poll panel told India’s top court in July. Even for the large-scale exclusion of 65 lakh names, the ECI tried to pass on the responsibility of correctness of the list to the Booth Level Agents (BLAs) of different political parties, while parties point out that it is the responsibility of the Booth Level Officers (BLOs), who are part of the administration.

What caused the ECI’s apparent change of approach—from ‘we must reach the last person’ to ‘aggrieved persons first need to reach us’? The question may have many answers.

While Opposition parties accuse the poll panel of carrying out the political agenda of the ruling establishment, the ECI insists the charges against it are politically motivated.

“When more than seven crore voters of Bihar are standing with the Election Commission, neither the credibility of the EC nor that of the voters can be questioned,” said Chief Election Commissioner (CEC) Gyanesh Kumar on August 17, dismissing charges of erosion in people’s trust in it.

The onus of proving citizenship, an essential part of electoral rights, lies on the electors, and not the ECI, the poll panel told India’s top court in july.

In a recent survey that the New Delhi-based Lokniti-Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS) conducted among 3,054 respondents across 30 districts in the states of Assam, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh and Delhi, respondents were asked, “To what extent do you trust the Election Commission—to a great extent, to some extent, not much, or not at all?” Of them, almost 60 per cent had trust deficits of various extents—37.4 per cent ranked their trust at ‘some extent’, 12.8 per cent said the trust was ‘not much’ and nine per cent had no trust ‘at all’. Only 28.6 per cent said they trusted the ECI to a ‘great extent’. There were another 5.7 per cent respondents who were not sure and another 6.6 per cent were not aware of the ECI’s existence at all.

The survey, titled ‘Documentation and Trust in the Voter Verification Process’, was released in August 2025. On being asked if they trust Electronic Voting Machines (EVMs) to record their votes accurately, only about 35.7 per cent answered, ‘Yes, completely’. The majority had trust deficits—28.8 per cent had ‘somewhat trust’, 14.1 per cent had ‘not much’ trust, and 10.2 per cent did not trust ‘at all.’ Another 11.1 per cent were unaware of the controversy to have any opinion.

The findings are reflective of a trend that a Lokniti-CSDS survey, titled ‘Social and Political Barometer Prepoll Study’, revealed last year. Asked how likely is EVMs’ manipulation by the ruling party, 17.2 per cent of the 10,019 respondents answered ‘a lot’ and 28.1 per cent said ‘somewhat’, while 11.3 per cent said ‘not much’ and another 15.9 per cent said ‘not at all’. On the extent by which they trusted the ECI, 28.3 per cent had mentioned a ‘great extent’, 30.4 per cent had trust to ‘some extent’, 13.6 per cent had ‘not much’ trust and 8.6 per cent reported no trust at all.

The ECI recently lodged two FIRs against psephologist Sanjay Kumar, co-director of Lokniti at CSDS, in a separate development regarding his comments on social media on the 2024 Maharashtra state election, accusing him of spreading misinformation. Kumar later issued a public apology. The Supreme Court granted him protection from arrest and ordered that no coercive action was to be taken against him.

Flash Point

August 17 was an eventful day. In the morning, the Lokniti-CSDS’ latest survey report was published. Around 1 pm, Congress leader Rahul Gandhi, the Leader of the Opposition in the Lok Sabha, kicked off the Opposition bloc’s Voter Adhikar Yatra (march for voters’ rights) from Bihar’s Sasaram. Ten days ago, he had made the sensational allegation of spotting 1,00,250 dubious votes in one assembly segment of a Karnataka Lok Sabha constituency.

From the Sasaram rally, Gandhi and other Opposition leaders took potshots at the ECI for colluding with Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

CEC Gyanesh Kumar’s 3 pm press briefing intensified the debate around trust. Instead of clearing the confusion created by Gandhi’s claims, he blasted the Congress leader. “...if you say that there are duplicate voters and some people have voted twice and call my voters criminals, it is not possible that the Election Commission will not react,” he said. The poll body head alleged that “politics is being done by targeting the voters of India by keeping a gun on the shoulder of the Election Commission.” He said the charges of irregularities amounted to insulting the Indian Constitution. He demanded that Gandhi either sign an affidavit or apologise to the nation.

Kumar also defended their decision against sharing CCTV videos of polling stations, a demand that Opposition parties raised to scrutinise unusual spikes in last-hour voting in many constituencies. Rather strangely, Kumar cited privacy issues. “Should the Election Commission share CCTV videos of any voter, including their mothers, daughters-in-law and daughters? Should we compromise with their privacy?” he asked. His remarks were oblivious to the fact that a polling station is a public place where the question of privacy is unlikely to rise. Highlighting that the ECI itself routinely posts photos and videos of women voters, transparency activist Anjali Bhardwaj alleged that the ECI was hiding “behind the facade of protecting women’s privacy” when CCTV footage has been sought for accountability.

Perhaps, the most significant aspect of the press conference was that the CEC defended not itself but the dignity and privacy of the voters and the Constitution. The CEC was objecting to the Opposition questioning “voters’ credibility” and insulting the Constitution. The ECI was, therefore, acting to protect the honour, dignity and privacy of the voters and the sanctity of the Constitution.

The Communist Party of India (Marxist) called Kumar’s press conference as one that “delivered the final blow” on the ECI’s institutional credibility. “In a combatively partisan intervention against the Opposition, he dished out a tissue of lies,” said the CPI(M), which is a part of the Opposition bloc, Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance (INDIA). “The brazen complicity between the Commission and the BJP could not have been more plainly exposed,” the party alleged.

The Escalation

Over the past few years, especially since 2019, Opposition parties have repeatedly tussled with the ECI over issues including alleged partisan treatment in cases concerning violations of the Model Code of Conducts involving leaders of the ruling dispensation and the Opposition. Concerns have been raised over the likelihood of tampering with EVMs and discrepancies in voter turnout data.

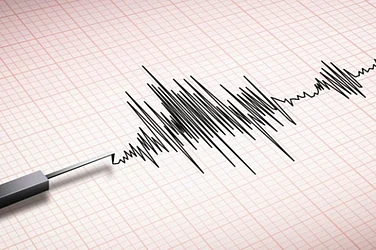

Since 2019, journalist Poonam Agarwal has been highlighting in a series of reports how there were noteworthy mismatches in the ECI-provided data on the actual number of votes cast using EVMs on polling day and the votes counted on EVMs on counting day. In a July 2024 publication titled ‘Report: Conduct Of Lok Sabha Elections 2024’, an organisation named Vote for Democracy claimed there was a hike of “close to 5 crore votes, or 4,65,46,885 to be precise” between the voter turnout figures reported at 7-8.45 PM on polling day and final turnout figures extrapolated from the data supplied by the ECI for all seats.

The way the ECI has apparently tried to evade transparency has also rung some alarm bells. In 2024, after some parties alleged an unusual spike in last-hour voting during the parliamentary elections, the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR), a New Delhi-based non-profit, approached the top court. They sought the judiciary’s direction to the ECI for disclosing the authenticated records of voter turnout by uploading on its website scanned legible copies of Form 17C Part-I (Account of Votes Recorded) of all polling stations after each phase of polling in the on-going 2024 Lok Sabha elections. However, in its affidavit, the ECI claimed that disclosure of voter turnout data could cause confusion among voters and such confusion could be “exploited by malicious interests” in closely contested elections. The poll panel told the Supreme Court that there is no legal provision mandating the disclosure of voter turnout during the general elections.

The ECI’s move to deny information citing the absence of a law was repeated during the Bihar SIR arguments in the apex court during July-August 2025. The poll panel argued that revealing a list of people excluded from the electoral rolls was not required by any law. The top court, nevertheless, rejected the ECI’s stance and asked it to publish the information along with explanations for exclusion. The ECI has said that 98.2 per cent of Bihar’s eligible voters have been verified through SIR, the remaining can approach the ECI to clarify why their names are not there.

Amidst all these controversies, the new law that the BJP government brought in and changed the system of appointing election commissioners awaits further hearing in the Supreme Court.

While observing that “a person weak-kneed before the powerful cannot be appointed as Election Commissioner”, a top court Constitution bench had, in a February 2023 judgement, ordered that the President of India will appoint the CEC and the ECs on the advice of a committee comprising the Prime Minister, the Leader of the Opposition and the Chief Justice of India (CJI). However, in December 2023, the BJP government passed a law that formed a committee but replaced the CJI with a PM-nominated member, thus tilting its balance towards the government. Even though the law was challenged in the apex court, the government went ahead with the appointed two of the three election commissioners under this law, including appointing Kumar as the CEC. The Supreme Court has not heard the case with the urgency that the petitioners and Opposition parties expected from it.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

(Snigdhendu Bhattacharya is a journalist, author and researcher)

Democracy is about ballots, but also about memory—who safeguards both, and who seeks to rewrite them? Outlook’s September 11, 2025 issue probes these erasures—of voters, voices, and histories—asking what they mean for India’s democratic future. This article appeared in print as 'As Goalposts Shift'.