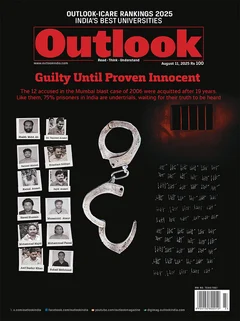

Waheed Ahmed Sheikh wiped the sweat and rain off his brow as he reached Bombay High Court on July 21, 2025. The monsoon in Mumbai can be stressful, but Sheikh was anxious for a different reason: he was entering a courtroom after a long time. He had been acquitted in the 2006 Mumbai train blasts case in 2015. The court was now pronouncing its verdict for the other men—twelve undertrials who had waited nine years for a trial court order and another decade for the High Court to decide their appeal against the sessions judge’s guilty verdict.

Earlier this week, a Special Division Bench of Justices Anil S. Kilor and Shyam C. Chandak set aside a lower court order that had sentenced five of the 12 accused to death and acquitted all the accused in what has been referred to as the ‘7/11 Mumbai Blasts.’

Once it decided that “the prosecution has utterly failed to establish the offence beyond reasonable doubt against the accused on each count,” the court said “it is unsafe” to conclude that any of the accused had “committed the offences for which they have been convicted and sentenced.”

Shortly after the verdict, the Maharashtra government filed an appeal in the Supreme Court, saying the High Court order would set a “dangerous precedent” in other terror cases. Solicitor General of India Tushar Mehta, appearing for the Maharashtra government, sought an interim stay on the High Court judgement. He argued that the judgement should not be used as a precedent before trial courts currently hearing other cases prosecuted under the Maharashtra Control of Organised Crime Act (MCOCA), telling a bench comprising Justices MM Sundresh and N. Kotiswar Singh. The apex court agreed and stayed the use of the order as a precedent.

“The Bombay High Court has done a rigorous job of analysing the evidence and showing why the evidence collected during the investigation was unreliable, manipulated, and based on torture. The law laid down on procedural requirements in MCOCA is very significant, thorough and in tune with constitutional jurisprudence. During the hearing in the Supreme Court, it wasn’t entirely clear what the concerns were with the reasoning adopted in the judgement,” said Anup Surendranath, Executive Director of Project 39A and an Assistant Professor of Law at National Law University, Delhi.

UP had the highest number of undertrials—94,131 out of 1,21,609 prisoners—followed by Bihar, which had 57,000 undertrial prisoners out of a prison population of 64,000.

Among those acquitted, Mira Road resident Asif Khan was one of the first to be released from prison that same evening. Still in tears, he had called Sheikh: “He said my acquittal had paved the way for his… that I had fought for them all while they were in jail and they would not forget,” Sheikh said, while sharing pictures with us that Khan had sent. In the photos, Khan was smiling, looking 19 years older than in the pictures from press conferences held by the 12 men’s families, civil society groups and Sheikh. Khan looked relieved, appearing to be enjoying his first taste of freedom at a biryani restaurant somewhere in Mumbai.

The Supreme Court, in its June 24 order, also said it would not interfere with the court-ordered release of the 12 men.

Sheikh and Khan’s stories are not exceptional. India’s criminal justice system currently has more than 434,302 undertrial prisoners—women and men who have yet to be convicted of any crime but await their trials inside prison. As of 2022, this figure represented 75.8 per cent of the total prison population of 573,220, according to the Prison Statistics India 2022 report. Uttar Pradesh had the highest number of undertrials—94,131 out of 1,21,609 prisoners—followed by Bihar, which had 57,000 undertrial prisoners out of a prison population of 64,000.

While many are convicted, a large number of undertrials are found innocent after spending years, even decades, in prison. This is especially true in cases involving serious charges like the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA), the MCOCA or sedition, where studies show that most cases do not result in a conviction. For these individuals, an acquittal may bring relief, but it does not compensate for their lost years.

The Long Shadow of a False Charge

Mohammad Aamir was just 18 years old when he was abducted from near his house in Old Delhi. He remembers it was a chilly evening in February 1998. The men who kidnapped him wore plain clothes, so he did not know they were police officers. They took him to an abandoned building where, he said, the first thing they did was: “strip my freedom and strip my clothes.”

For seven days, the men held Aamir in the abandoned building—in illegal custody—and tortured him. “They forced me to sign blank sheets of paper,” he added. After a week, the police produced him in court, claiming he had masterminded over 20 bomb blasts across North India.

Aamir spent the next 14 years in jail. Charged under draconian laws like the UAPA, he was transferred between prisons as trials took place in Delhi, Ghaziabad, Rohtak and Ludhiana. He spent over a decade fighting the 19 different cases against him in sessions courts across North India—Delhi and Rohtak. One by one, the courts dismissed the prosecution’s charges against him. In some instances, the evidence was missing altogether.

“The first 12 cases went by very quickly,” Aamir said, but the final few cases dragged on for nearly a decade. When he finally walked out of jail, his father had died; his mother, paralysed by a stroke, no longer recognised him. He was 32.

The Rot in the System

“A narrative is built, and then the police and prosecution look for people to fit that story,” said Naveed Mehmood Ahmad of Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, adding that “the idea is not to get a conviction. The idea is to put someone in jail for as long as possible. That is the punishment.”

Ahmad pointed to sensationalist stories by the media, bias by the prosecution and the police and public pressure merging to create an atmosphere where the accused’s fundamental legal rights collapse.

“It becomes impossible to get bail, especially in UAPA cases,” Ahmad explained, adding that “the trial courts are often reluctant to give bail, perhaps also hesitant to question the State in national security cases. So, trials go on for years.”

For the courts to penalise an officer for malicious prosecution or false arrest is rare, almost “never,” said Ahmad, adding that, “The State doesn’t suffer. The individual suffers. There is no accountability.”

Ahmad says this is particularly stark in cases involving minorities, including Muslims.

Shattered Safeguards

In 2023, the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) reported that more than 60 per cent of undertrials had been in jail for over two years without even facing trial. Many of them spend more time in prison than the maximum sentences for the crimes they are accused of. According to IndiaSpend, since 2010, the proportion of undertrials detained for over one year has fallen by seven per cent, while the number of undertrials jailed for more than three to five years has doubled.

As of 2022, young adults made up a large portion of India’s undertrial population—about half of India’s 4.3 lakh undertrials were aged 18–30, according to NCRB data. Dalits and Adivasis, who make up around 25 per cent of India’s population, accounted for 45 per cent of prisoners.

The UAPA, which was enacted to fight secession and terrorism, has been described by legal experts as a political tool. In recent years, activists, students and even journalists have been booked under the Act. A report by the People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL) found that over 70 per cent of the UAPA cases end in acquittal. Similarly, a 2021 NCRB report shows that from 2016–2020, of the 24,000 people charged under UAPA, only 212 cases resulted in conviction and 386 people were acquitted; at the time of the report, the rest remained under trial.

The Supreme Court and the Law Commission of India have repeatedly emphasised the importance of a “speedy trial” as a constitutional right. In practice, however, bail has become the exception. The 2017 Law Commission report stated that trial courts must set “reasonable” bail conditions so that the accused are not indefinitely imprisoned.

In some states like Goa, acquittals and discharges are more common than convictions. In 2022, Goa had 1,283 acquitted vs. 452 convictions. The courts reportedly had said the most common cause for the high acquittal rate was lack of evidence put forth by the prosecution.

No Compensation; No Accountability

India has no statutory provision to compensate for wrongful incarceration. Sheikh was acquitted in 2015. He received no compensation. In Sheikh’s case, he said that the investigating officer (IO) came up to him and apologised for prosecuting him. “He told me he was under a lot of pressure from his seniors,” Sheikh said. However, the IOs in both cases were not censured—no charges of wrongful prosecution or perjury were brought against them. The IO in Sheikh’s case was later picked up on a separate corruption charges related to bribery.

“Although initiating false prosecution and giving false evidence are offences punishable under the IPC (and now the BNS), there is no culture in this country where, once the case falls apart, one can go back and ask these questions and initiate an inquiry about why this kind of shoddy evidence was produced. The only instances of cases being filed for initiating false prosecution that I can think of are those where, upon a change in government, cases were lodged against persons who had initiated prosecutions against political leaders,” said Nizam Pasha, an advocate who has argued constitutional cases in the Supreme Court and also defended undertrial prisoners.

In July 2025, the Indian Supreme Court pointed out that it was time for the state to begin compensating undertrials who have experienced wrongful detention due to errors or delays in their release. In a recent case, the court ordered the Uttar Pradesh government to pay Rs five lakh in compensation to a man who was illegally detained for 28 days following his bail order, citing a clerical error. The top court emphasised that liberty cannot be denied based on “frivolous technicalities” and “irrelevant errors”.

The NHRC took up Aamir’s case in 2014. Four years later, the Delhi police gave him Rs five lakh for his pain and suffering— Rs 97 per day for his 14-year-long incarceration.

His voice was soft but unwavering when he said: “It can never compensate me for all I lost in that time, but at least there was some action.”

The pursuit of any remedies in civil law is rare, said Surendranath. “We must realise that individuals who are subject to wrongful prosecutions and wrongful convictions come from extremely vulnerable sections of our society. The capacity to fight injustice and gain their freedom is itself a mountain to climb. To then have the wherewithal to fight for further remedies is something our system does not facilitate. Even before that, there is not even a meaningful acknowledgement in our system that wrongful prosecutions and wrongful convictions are a serious problem in our criminal justice system,” he said.

In the 7/11 Mumbai blasts case, the High Court noted that the confessions submitted as evidence by the prosecution were coerced from the accused. Sheikh described the officers torturing him several times during the investigation stage. “They would call me day after day and I would go. Sometimes they would beat me up in front of the other people they were questioning; sometimes they would torture them in front of me,” he said.

It is, however, unlikely that officers involved in these acts will see accountability either. “I doubt very much that the finding, that the confessions were not voluntary, will result in the state acting against the officers involved. Accountability for custodial torture in India has been incredibly difficult, with barely any successful prosecutions,” said Surendranath.

The Afterlife of Injustice

When Sheikh left prison, it was an uphill battle to return to teaching. He went back to the school where he had once taught Urdu. But the principal told him parents would not accept it. “People from my community and civil society had to take up my cause; tell the principal that he is acquitted and there is nothing to worry about,” Sheikh said.

Not everyone is that lucky. Aamir said that he had a lot of trouble finding a job after his release. “When the prison doors open, the doors to other challenges also open (with it),” he said. Aamir, who loved looking up at the open sky and dreamed of being a pilot, now works full-time on prisoner rights, runs workshops for lawyers and helps document cases of wrongful incarceration. Aamir’s own family was decimated by the justice system, but according to him, helping others is also a kind of justice.

Both men still carry the scars of false imprisonment. The label of “terrorist” lingers like a shadow. Sheikh’s house has been raided so many times since his release that he says even the sound of a knocking on the door gives him heart palpitations. “My children start crying… ‘Papa, we won’t let them take you again.’”

Aamir, too, is haunted by the memories of his time in prison. “I wake up sometimes in sweat after having dreams about the prison, the torture… Sometimes my wife tells me I was screaming in my sleep,” he said.

Outlook Magazine’s next issue, “Guilty Until Proven Innocent”, looks at the 19 years lost of those who were in jail and those who thought justice was served, until it wasn’t. This article appears as 'The Waiting Room' in the magazine

.jpg?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max&format=webp&w=768&dpr=1.0)