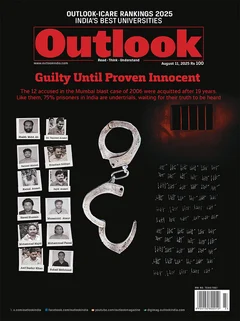

When the Bombay High Court on July 21 declared 12 prisoners not guilty after the bench found the prosecution had “utterly failed” to prove their involvement in the 2006 Mumbai suburban train serial blasts for which five of them had been sentenced to death and seven to life imprisonment in 2015, 40-year-old Mumbai resident Chirag Chauhan could feel his old wounds reopen after the same two decades the accused had spent in prison until acquittal.

On July 11, 2006, when the lifelines for the city’s working class had become sites of carnage with seven blasts ripping through trains on the Western Railway line in a span of 11 minutes during the evening rush hour, killing 189 people and injuring over 800, it changed Chauhan’s life forever. “I don’t remember the explosion,” he says. “I just remember waking up in a hospital and not being able to feel my legs.” The blast had severed both his legs below the knee.

Just minutes before the explosion, Chauhan had boarded the Borivali-bound train from Churchgate, like he always did. He was on his way home to Kandivali at the end of a day of his articleship at a chartered accountancy firm. Chauhan smiles as he recalls he had left earlier than usual on that day and wonders how drastically his fate would have been different had he stuck to the routine more exactly. But, then, who could have known his early exit from office would give him a new identity, a new self, before he finally reached home?

For months, Chauhan, then 21, was bedridden. The pain wasn’t just physical; it was the kind that cracked open a person’s belief in the world’s fairness. His youth was abruptly interrupted and his independence taken from him. What followed was a long, agonising process of learning how to live again. Today, Chauhan owns a chartered accountancy firm in Malad and lives with his family in Kandivali. There is a certain edge to his voice—otherwise calm and measured—when he talks about the acquittals. “Who is guilty if these men are not?” he asks, clarifying that he wants answers, “not revenge”.

“Someone planned those blasts. Someone executed them. We need to know who did it. Otherwise, what’s the message? That you can kill 189 people and just walk away?”

Remembering the days when he had just begun his journey to become a chartered accountant—a time when he was standing at the edge of adulthood, with the confidence and clarity only youth brings, while nurturing his aspiration with discipline, focus and the quiet support of his middle-class family in Mumbai—Chauhan asks why his life was never allowed to unfold the way he had imagined it.

Back then, his days were filled with textbooks, late-night study sessions, and thoughts of a future shaped by hard work and integrity. He was determined to build a life of purpose—respectable, professional, and far removed from the world of crime and controversy. No wonder news of the acquittals brings him not just confusion but also anger, helplessness and a deep sense of having been forgotten. And the feeling that justice was not just delayed, but not done at all.

For Mahendra Pitale, who was 33 at the time of the blasts, the tragedy didn’t just claim a piece of his body. It took something far more intimate and irreparable: a piece of who he was. A sculptor and art designer by trade, whose identity was inseparably tied to his craft, Pitale lost half of his left hand when the explosion tore through the coach of the Borivali-bound train he was in. “I remember trying to get up from the railway track. Everything went dark. I woke up and my hand was just not there,” he says.

In the world of intricate lines and delicate curves, Pitale was known for his unmatched precision, his steady hands, and a quiet, almost meditative discipline that set him apart. Admired by his peers, he was the kind of artist who could bring stone to life and turn clay into poetry. All this changed in a single, deafening instant on the train. The explosion didn’t just tear through metal and flesh; it ruptured the life Pitale had so carefully shaped for himself. He survived, but the physical injuries were only the beginning. The blast left him permanently disabled in one arm, the very limb that had, for years, translated imagination into form.

In the months that followed, he struggled not only with pain and recovery but with a profound sense of dislocation, too. Who was he now if he could no longer sculpt? How does an artist exist when denied his most fundamental tool? It wasn’t just the loss of a limb; it was the loss of rhythm, confidence, independence and the unspoken fear that he might never again feel the way he used to.

The injury would have ended the careers of many. But Pitale, now 52, never let it become an excuse. He now works with the Indian Railways at the Mumbai central office and lives alone in suburban Mira Road. His apartment walls are lined with marathon medals, photos from Republic Day parades, and plaques from government events where he was honoured for his resilient spirit. A passionate biker, he has modified his motorcycle. “When you survive something like that,” he says, “you either give up or you double down on life. I chose to fight.”

Yet, even he, a man not easily shaken, went numb when he heard about the acquittals. “What took the judiciary and government 19 years to decide something so basic?” he asks. “You want to tell me all these years of trial, all the statements, the evidence…none of it was real? Then what about our pain? Was that fake too?”

“I attended every hearing I could. I sat through the trial. I believed in the system. I thought, yes, it’s slow, but it will deliver. I was wrong. It took nine years to convict and 10 more to acquit. That’s not justice. That’s an insult.”

It was on finding “serious lapses and contradictions” in the prosecution’s case, however, that the court had declared inadmissible the confessions, recorded under the Maharashtra Control of Organised Crime Act (MCOCA), on which the convictions by the sessions court were based. The Anti-Terrorism Squad (ATS) of Mumbai Police had arrested several suspects linked to the Students’ Islamic Movement of India (SIMI), an outlawed outfit. In the years that followed, allegations of coerced confessions, fabricated evidence and custodial torture cast a shadow over the probe. Legal experts and human rights groups raised concerns about due process, lack of corroborative evidence and the possibility of wrongful conviction. While the high court verdict acknowledges these concerns, it also triggers an old question: what happens to survivors of violence when the system fails to deliver justice?

Over the years, Chauhan learned to live with his disability. He embraced technology, took therapy, joined Sukyo Mahikari, a Japanese spiritual movement that focuses on spiritual purification, and built a life that, on the surface, looks enviable: a fulfilling career, a strong support network, and a quiet but unshakable dignity. Technology—voice activated tools, smart home systems, customised support devices—became his bridge to independence and he found empowerment in innovation. Beneath that composed exterior, though, lies a hope that never faded—the hope of one day walking again. As new breakthroughs in medical technology and neuro-rehabilitation emerge, Chauhan follows them closely, with a cautious optimism. For him, the future isn’t about restoring the past; it’s about the possibility of reclaiming movement, freedom and, perhaps, a small piece of the man he once was.

“I have moved on from the incident and living my life to the fullest,” Chauhan says with a smile. “My family knows it’s been a hard day. This year, it was worse. I kept thinking, if there’s no one guilty (of the blasts), then was I just unlucky. Was this random?”

Pitale, too, has spent the past 19 years rebuilding, reinventing and refusing to be defined by the tragedy. Yet, his frustration with the legal system has grown with each passing year. “I attended every hearing I could. I sat through the trial. I believed in the system. I thought, yes, it’s slow, but it will deliver. I was wrong,” he says. “It took nine years to convict and 10 more to acquit. That’s not justice. That’s an insult.”

While both Chauhan and Pitale say they are not against the acquitted individuals as the innocent deserve to walk free, they insist someone must be held accountable. “The government, the security and investigation agencies, or the judiciary…someone has to be held accountable for this lapse,” Chauhan says. Pitale says the state now has a moral obligation to reopen the investigation, “not for vengeance, but for truth”. “Someone planned those blasts. Someone executed them. We need to know who did it. Otherwise, what’s the message? That you can kill 189 people and just walk away because of loopholes?” he says.

Chauhan today mentors aspiring chartered accountants, while Pitale continues to run half-marathons and delivers motivational talks at schools and colleges. When asked how they find the strength to carry on, Pitale laughs softly. “What choice do we have? The system may forget us. But we can’t afford to forget ourselves,” he says, while Chauhan takes a deep breath and adds “If the law of the land fails, the law of god does not.”

The survivors of 7/11 were promised support, compensation and rehabilitation. While some monetary compensation was given by the state, most say it was neither timely nor sufficient. What hurt more, many claim, was the lack of continued engagement. As Mumbai continues its daily rhythm, the survivors live with a silence louder than any explosion: the silence of a system of justice that could not give them answers even after 19 years. The survivors, though, haven’t stopped asking, “Who will give us justice?”

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Jinit Parmar is a senior correspondent, Outlook. he is based in Mumbai

Pritha Vashishth is Outlook’s Mumbai-based correspondent

Outlook Magazine’s next issue, “Guilty Until Proven Innocent”, looks at the 19 years lost of those who were in jail and those who thought justice was served, until it wasn’t. This article appears as The Unconsoled.