Raavan's story has been obscured over centuries, appropriated and simplified to serve vested interests, including the political narratives that gained momentum after the demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992 and the consecration of the Ram Temple in Ayodhya earlier this year..

Communities like the Asurs and Adivasis reclaim Ravana as ancestor and hero.

His story reveals contested histories, cultural memory, and human complexity.

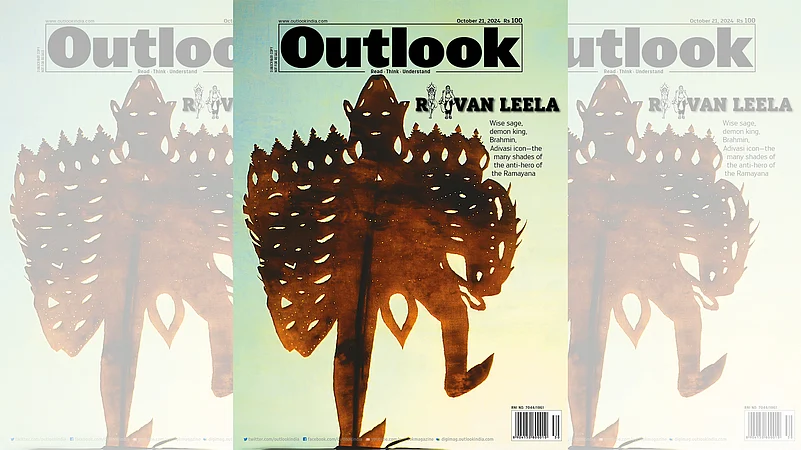

There has always been a kind of sadness that lingers after the effigy of Ravana turns to ashes. His very name, Raavan, means ‘bluebird’ in the Gondi language, a detail that hints at a lost cultural memory, Outlook's Editor Chinki Sinha writes in Outlook India’s October 21, 2024, magazine titled Raavan Leela. The issue invites readers to look beyond the familiar story of Rama, Sita, and the ten-headed demon king, Ravana.

In her piece "Raavan Redux: The Anti-Hero’s Many Dimensions", Sinha argues, that Raavan's story has been obscured over centuries, appropriated and simplified to serve vested interests, including the political narratives that gained momentum after the demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992 and the consecration of the Ram Temple in Ayodhya in 2024. Ravana, once a complex and multi-dimensional figure, became a symbol moulded to fit particular ideologies, and in that process, the nuances of his character were largely forgotten.

Sinha’s reflection sets the tone for the magazine’s exploration of Ravana, highlighting his intellect, devotion, and moral complexity. He is portrayed not just as the villain in Sita’s abduction, but as a scholar, a strategist, and a devotee of Shiva, whose ambitions and flaws make him profoundly human. The magazine challenges the simplistic good-versus-evil framework of Dussehra narratives. It urges readers to consider how myth and history intersect and how narratives can reinforce specific ideologies while erasing nuance.

This re-examination is echoed in "Countering the Traditional Raavan Narrative", which highlights the work of scholars and communities who challenge Ravana’s one-dimensional portrayal. By emphasising his accomplishments, the article shows how demonisation obscures the breadth of his character. Here, Ravana is not simply a cautionary tale but also a reflection of leadership, cultural memory, and human complexity.

For the Asur community of Jharkhand, this reassessment is deeply personal. In "For Asurs of Jharkhand, Raavan Is Not a Demon But Their Own", Outlook details how the Asurs honour him as a hero and ancestor, integral to their cultural identity. To them, the Ramayana’s dominant narrative does not capture the reverence and pride with which they remember him. Through their oral histories, rituals, and local traditions, Ravana emerges as a figure whose story embodies resilience and a sense of belonging, offering an alternative lens to the one familiar in mainstream culture.

The emotional resonance of Ravana’s life is further explored in "Why People Cry When Raavan Dies". While Dussehra is associated with celebration and the burning of effigies, there exists an undercurrent of sorrow for some communities, who see the destruction not just as the defeat of evil but as the erasure of a complex figure whose life contained ambition, intellect, and tragedy. This article illuminates the layers of feeling intertwined with ritual, reminding readers that mythology is not simply entertainment but a vessel for collective memory and emotion.

The magazine also explores literature as a medium for understanding Ravana’s multidimensionality. In the poem "In the Island Kingdom", Ravana is reimagined in lyrical form, bringing to life his passions, flaws, and ambitions. Through evocative language, the poem portrays him not merely as a mythological antagonist but as a character capable of evoking empathy, reflection, and introspection. Here, poetry allows for the exploration of nuance and the humanisation of a figure long flattened into a symbol of evil.

Historical inquiry continues in "The Native King: Raavan and the War That Never Happened", which questions the traditional narrative of the war between Rama and Ravana. Drawing on regional folklore and oral histories, the article suggests that the legendary conflict may have been mythologised, with stories reshaped over time to suit ideological agendas. Ravana is presented as a native king whose historical and cultural significance cannot be reduced to the label of villainy, highlighting how myths evolve alongside societies and politics.

Finally, "Tracing an Adivasi Ancestry Line to Raavan" illustrates how certain Adivasi communities claim Ravana as an ancestor. For them, he is neither a demon nor a villain, but a symbol of lineage, heritage, and identity. This reclamation challenges dominant narratives, demonstrating how mythology intersects with culture, memory, and pride, and how a figure once vilified can be reinterpreted as central to a community’s historical consciousness.

Taken together, these articles in the issue paint Ravana not as a one-dimensional villain but as an anti-hero, a scholar, a king, an ancestor, and a figure whose story has been reclaimed, reshaped, and remembered in many ways. Dussehra, often defined by the burning of effigies and the triumph of Rama, is presented here as an occasion to reflect on complexity, to look beyond spectacle, and to recognise the layered, contested narratives that history, myth, and culture can produce. Ravana, in all his dimensions, becomes a mirror through which we can examine morality, identity, and the very process of storytelling itself.