The rain has been a character in Hindi cinema for many decades now, with filmmakers using it as a plot device.

Especially for scenes of intimacy, the rain has been a repeatedly used catalyst to create iconic rain songs.

Although rain songs are fewer in number now, rain is still used to depict emotions like love, pain, nostalgia and heartbreak.

When you want to up the ante on sizzle for a scene in Hindi cinema or just take intimacy to the next level, or better still, set the stage for forthcoming sex (usually followed by a pregnancy announcement), nothing works like rain. The heavier the downpour, the whiter the clothes, the better—although the lead hero and heroine always manage to find a cosy den somewhere to camp, and there is always a fire and some blankets, as though someone had called housekeeping in advance. Unbeknownst to the two parties, the stage for sex is set.

Hindi cinema and baarish is an enduring tale of romance and it still continues, even as recent as Metro…In Dino (2025), which explores relationships across different age groups, where the rain is an observer—flowing through their joys, conflicts, and silences. But baarish has been around for ever, not just as a background character, but often an integral part of the narrative, a mood, a metaphor: it heightens love and desire, heartbreak and nostalgia in equal measure. Sometimes, it's two lovers reuniting on a soaked street; at other times, a heartbroken soul finding solace under stormy skies; or the anticipation of a meeting set to the sound of gentle drizzle (Think “Oo sajna barkha bahar aayi” from Parakh, 1960).

In Kaagaz ke Phool (1959), filmmaker Suresh Sinha (Guru Dutt) is returning after a not-so-good meeting with his estranged wife, a storm brewing inside him and aptly, outside. He finds shelter under a banyan tree and realises there’s a poor, young girl (Waheeda Rahman) sneezing and shivering in the rain. He asks her, “Aap apna garm coat kyon nahin laayin?” She replies, “Zukam muft milta hai, garm coat ke paise lagte hain.” He smiles and before leaving, puts his overcoat around her. It’s their pehli mulaqaat. There’s no romance, but you already know that this meeting is going to change the course of their lives.

In Shree 420 (1955) on a rainy evening, Raj Kapoor and Nargis share a timeless, magical moment walking into the distance under an umbrella, sharing tender smiles and a growing connection. As the rain pours down around them, the lyrics of “Pyaar hua Ikraar hua” perfectly complement the mood, expressing the sweetness of falling in love. The scene encapsulates the charm and innocence of their romance, making it an unforgettable part of Hindi cinema’s golden era. (In later years, the umbrella was replaced by the hero’s jacket, which is carefully thrown over them as they embrace).

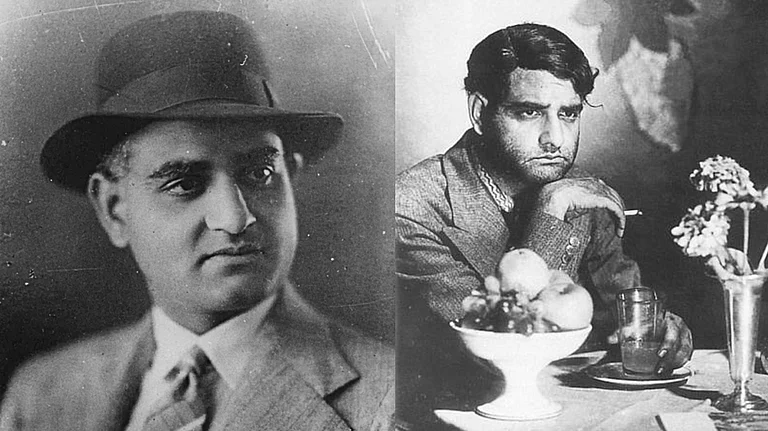

In “Rimjhim ke taraane” (Kala Bazar, 1957), the camera pans across a row of people with umbrellas, before settling on Dev Anand with a newspaper over his head.

Ek ladki bheegi bhaagi si in Chalti Ka Naam Gaadi (1958) is another classic. Set in a dimly lit garage on a rainy night, the scene begins when Renu (Madhubala), drenched from the downpour, seeks help for her broken-down car. There, she meets the flirty and mischievous mechanic played by Kishore Kumar. As the song unfolds, he teases her playfully while she shivers in her soaked sari, visibly annoyed but amused. The rain adds a romantic tension to their banter, while the song’s light-hearted melody and cheeky lyrics turn the scene into an unforgettable mix of flirtation, humour, and chemistry.

Getting drenched in Hindi cinema (almost always in pouring, roaring thunderstorms that emerge on cue) is invariably a precursor for bursting into a song. Sometimes, for two people in love, there is more than the song—there are racing hormones, clothes being dropped (because, zukam ho jaayega) and the heroine is always ovulating for some reason, leading invariably to the pregnancy announcement with the “Main tumhare bachche ki maa banne wali hoon” dialogue in a few days or weeks (as in Aradhana, (1969), soon after “Roop Tera Mastana” of orange sheet fame). More often, though, the two people concerned realise post getting drenched and disrobing to get into a blanket or sheet or whatever is available, that this friendship is anything but platonic. Somehow, the heroine always has a knack for getting soaking wet (unlike the hero who remains mostly bone dry) and needs to change and the hero surprisingly has packed an extra shirt, because ‘what if I get lucky tonight’?

If you are Manmohan Desai, you don’t even need sex to get the heroine pregnant. Just transference of body heat is enough. In 1973’s Aa Gale Lag Ja, Sharmila Tagore and Shashi Kapoor are caught in a hailstorm. Freezing and shivering, Kapoor gets on top of his co-star to warm her up, and ends up impregnating her. MKD applied the same "'body heat” technique to Amitabh Bachchan and Meenakshi Seshadri in Ganga Jamuna Saraswati (1988). It worked again.

I love the rain too, but ultimately, cannot wait to get out of my wet clothes and remember how hard that is (try getting out of wet skinny jeans and you will know). To top it all, who the heck wants to drape a dubious blanket and writhe around on hay or some such while you’re wet? And how is it that all these deserted buildings and caves always have stray blankets/ sheets/ whatever for these heroines to change into? The exception to this is “Roop tera mastana”, where they are at least shown to take shelter in a guest house.

Rain also gives a gloomy energy to a situation, like in Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali (1955), in which a poverty-stricken-household meets further despair when their daughter Durga gets drenched in a downpour and passes away the next morning. Even in Karan Johar’s K3G (2001), Anjali’s (Kajol) father’s death is accompanied by a downpour to add to the heaviness of the moment, and in Wake Up Sid (2009),the rain adds gravitas to its climax. Director Ayan Mukerji uses the rain to symbolise that the reunion of Sid and Aisha means something new, something mature, something deeper.

Although rain songs have significantly reduced in number in the past decade, but the rain continues to feature as a leitmotif in cinema. All you need is to sprinkle a little rain to create a moment that sticks. Often a match-maker and a door to emotions, the rain catalyses both new love and goodbyes. Something always changes in the mood when it rains—either for the characters on screen or within us. And cinema knows this.