The lost and formula has been a Hindi cinema favourite for four decades.

Manmohan Desai, Nasir Hussain and others have made several blockbusters using the trope.

Losing and finding family is largely the motivation of most plots in the 60s and 70s

It is a truth universally acknowledged that before the term ‘parenting’ was invented, every parent has, at some point, lost a child in a public place. Yours truly has been lost twice—first, by my father in a covered vegetable market when I was four and two years later, by my mother, who got on a train and left me behind on the platform. In both cases, I was duly found and reunited with my parents, so it was a happy ending. In the first, a vegetable seller hoisted me on to his stall and gave me a bunch of carrots to chomp and told me my father would realise at some point and come back. He did. In the second, I wandered to the Station Master’s office; he offered me tea and biscuits and made an announcement. It all felt very important. I remember thinking how lucky I was and had this been a movie, I probably would have met my parents only as an adult.

In my 16 years as a parent, I came close to losing my kid once, when I left him fast asleep in his stroller while I stopped to grab a coffee at the airport and before boarding, realised I had one piece of luggage missing and ran back. There were 200 pairs of eyes staring at me. At least I wasn’t Nirupa Roy, I consoled myself; she probably wins hands down in the ‘losing my children’ competition, often proceeding to lose her memory or her eyesight or voice soon after.

One often wonders why Bollywood always glorified Maas and Pitajis, despite some of them blatantly losing one or all their children. But Hindi cinema has always been in love with the idea of lost-and-found children/parents/friends/sweethearts for a long time and has continued using the formula in one form or another for well over four decades. Maybe, because family was always central to the movies of yore — and when one or more of it is lost, it really shapes you as a person and defines your arc. When family is lost, your core is lost, and so, finding family is largely the motivation of most plots.

There were various factors that catalysed the losing: Over-optimism, carelessness (or just having more than one child, as in the case of 1977’s Amar Akbar Anthony or 1965’s Waqt), trust in strangers, natural disasters—usually in the form of earthquakes (Waqt) or floods—or even a large gathering, like VT station or a mela (Mela, 1971) . The phrase mele mein bichhde hue bhai probably came from here. Sometimes, it was just bad karma (villains gunning down mama and papa, leaving the children to fend for themselves) as in Yaadon Ki Baarat (1973) or children just randomly left in a park—while father goes to hide smuggled gold, mother goes to find father, hits a tree, is blinded and never returns; children are left wondering what became of them, and they get separated too, each one rescued by a stranger of a different faith (Amar Akbar Anthony)

Sometimes it’s also a baddy kidnapping a good guy’s child (Dharam Veer, 1977) as if to say, “wait till I make him baddy 2” , and having the last laugh. But why bother bringing up another person’s child, I wondered. Raising one’s own (and not losing them) is challenging enough for the most part.

Sometimes, the child is separated from one parent; sometimes, from both (and the parents are also separated from each other), and in the grandest version, the entire family—mother, father and children (multiple)—are adrift in different directions, as in Amar Akbar Anthony.

Getting lost makes one's life take a different trajectory—in Hindi cinema, more often than not, it’s the realm of crime. Sometimes, the son of a respectable family becomes a petty thief (Kismet (1943), Boy Friend (1961), Waqt (1965)); sometimes, three brothers grow up in different faiths (AAA).

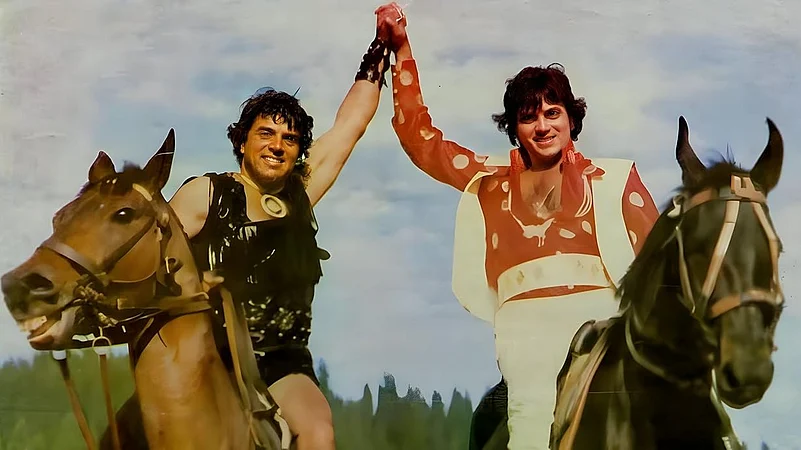

While Manmohan Desai was the king of the lost-and-found trope, with the first few reels of every film totally dedicated to losing children at an alarming rate (AAA, Chacha Bhatija (1977), Bhai Ho To Aisa (1972), Naseeb (1981), Rampur Ka Lakshman (1972), Parvarish (1977), Dharam Veer), Nasir

Hussain came quite close (Tumsa Nahi Dekha (1957), Pyar Ka Mausam (1969), Yaadon Ki Baarat, Hum Kisise Kum Naheen (1977)).

After a series of improbable happenings, crazy coincidences and implausible devices, the twain or trio or the big fat family finally meet and live happily ever after. It’s funny how the ‘finding’ always happens years later, well into adulthood. The lost-and-found had various permutations and combinations: Father and son, husband and wife, brothers who were not twins, identical twins, fraternal twins and later, even twin sisters.

Another popular trope of the time has been the lost-and-found sweethearts, who are almost always connected by a song. It’s funny how they remember the song the exact same way as adults. Case in point: Tariq and Kajal Kiran of Kya hua tera vada fame (Hum Kisise Kum Naheen) or O saathi re with Amitabh Bachchan and Rakhee in Muqaddar Ka Sikandar (1978). Sometimes, it’s also sweethearts who are married in childhood but lost as adults, like Guru Dutt and Waheeda Rahman in Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam (1962).

Enough about the losing. Let’s talk about the finding.

Sometimes, injury helps. In case of memory loss of the Nirupa Roy kind, a jolt is often a good idea, helped by hitting one’s head on a large stone or ramming into a tree, or even better, hitting your head on a temple bell, or just waiting to be washed by the illumination of a religious statue. In Amar Akbar Anthony, three brothers show up to donate blood to Nirupa Roy (for a head scrape), not knowing she is their mother. Nobody told them that mothers and children have different blood groups—but that is too much science for Hindi cinema. For her part, the mother is conveniently blind; but even if she wasn’t, how would she recognise her children, who have grown up to be strappy young men?

Moles are useful too, or better still, tattoos of a certain kind, like your name. Sure, it’s painful to subject a child to this, except if you are father who believes that a mard has no dard, and you inscribe that on your infant son’s chest (Mard, 1985) as he bleeds and gurgles, only to find him decades later. Sometimes not having a mole is also an identification, as in Biwi O Biwi (1981), in which both Sanjeev Kumars pull down their pants to realise neither of them has a birth mark, so they must be related.

Despite being careless in other ways, parents often endow their child/children with a locket or a taaveez, just in case. The child, of course, grows up with no sense of fashion, wearing the same locket the parents bestowed upon them—never losing it, never outgrowing it, and always displaying it in a manner that immediately identifies them. In Yuvraaj (1979), Vinod Khanna is the long-lost prince of a kingdom, and is finally identified by a taaveez and a little baby shirt of his. Mela also used a taaveez to reunite brothers Feroz and Sanjay Khan.

And then there is the family song, like Yaadon ki Baarat nikli hai (in Yaadon Ki Baarat), which reunites siblings Dharmendra, Vijay Arora and Tariq; Aaj kal mein dhal gaya reuniting siblings Sunil Dutt and Jamuna in Beti Bete (1964); or Tum bin jaun kaha for father-son Shashi Kapoor and Bharat Bhushan in Pyar Ka Mausam. Family songs are also ominous in that whenever there is one (usually different versions played in the same movie several times), you know a separation is coming up. But how long can you wander around singing the family song, waiting to be found? The answer is—really long. Just keep practising.

Sometimes, it’s just enough to play a sport in your childhood, like boxing—so that when you grow up and meet your long lost brother, you instantly recognise the other from their boxing moves like Dev Anand and Pran in Johny Mera Naam (1970).

The lost-and-found formula is said to have debuted with Kismet, featuring Ashok Kumar as the good and bad guy, which was remade about two decades later as Boy Friend with Shammi Kapoor. But theories abound that it started long before that, with India’s first feature film Raja Harishchandra (1913). The finding device was a ring.

Whatever the origin, the trope had a really good run and made for great entertainment and a paisa vasool feeling whenever you left the theatre. I guess the disappearance of the lost-and-found formula is partly because it is becoming increasingly difficult to get totally lost these days, with the internet, with cell phones and Googlemaps. But I still miss it. And I want someone to do it all over again, Manji style.