Summary of this article

Direct Benefit Transfer schemes mobilised unprecedented women’s turnout, breaking caste voting patterns and consolidating support for incumbents.

Cash transfers before elections helped several governments —including in Bihar, Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra — convert fatigue into sweeping mandates.

Experts warn that normalising cash-linked electoral loyalty risks weakening accountability and reducing governance to transactional welfare.

Aarti Devi, a 39-year-old Adivasi woman from an Adivasi settlement in Bihar’s Rohtas district, lists her community’s many grievances: “We don’t even have proper housing. There’s no road to our Tarachandi settlement. The men migrate to other states for work, and we take whatever work we can find nearby. Leaders come only during elections; after that, no one checks on us.”

After detailing these complaints, she confirmed that the Bihar government’s ₹10,000 transfer had reached her account. She gestured toward a cart beside her and said she had used the money to buy it and planned to start a small snack stall.

So whom did she vote for? “The one who gave the money,” she murmured.

In Tarachandi, an Adivasi settlement of about six hundred households, most residents echo Aarti Devi’s complaints. Yet the ₹10,000 deposited into women’s bank accounts under the Chief Minister Women Employment Scheme—launched just before the Bihar Assembly election announcement—has clearly influenced Adivasi women here as well. Their grievances against the government and elected representatives remain, but the quiet admission that votes were cast for the money shows how strongly DBT schemes shaped the NDA’s sweeping mandate in Bihar.

The irony is striking: the same parties that once dismissed direct cash transfers for women as “freebie culture” are now using these schemes most aggressively to retain or gain power. The shift reveals where real politics has moved when measured against past ideological critiques and present electoral calculations.

Once data began showing that women voters, especially from poor and rural backgrounds, respond with organised and loyal support to direct benefits, even those who mocked “freebies” adopted the same path.

Bihar may be the most prominent example today, but this style of politics did not begin here.

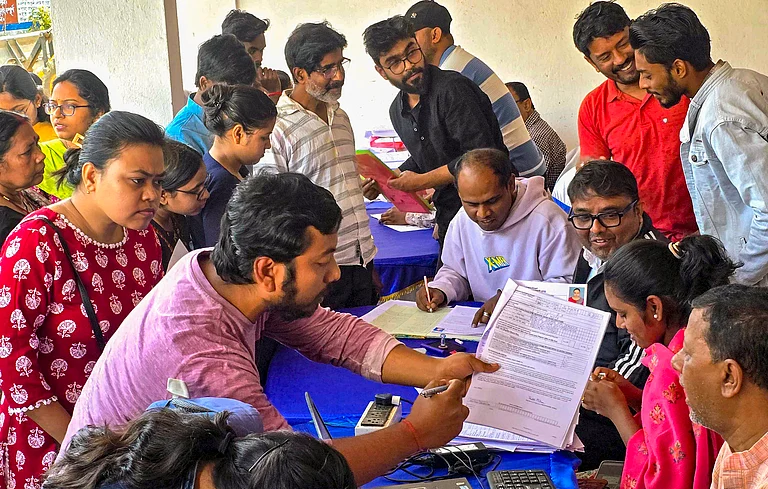

It can certainly be said that in the name of women’s empowerment, the scale and amount distributed through DBT in Bihar has been the highest. Nearly 1.5 crore women received 10,000 each directly into their bank accounts from the Bihar government under the Chief Minister Women Employment Scheme before the election announcement.

Election analyst and founder of Data Action Lab for Emerging Societies, Ashish Ranjan, believes that political parties have now begun using such schemes as a weapon to counter anti-incumbency just before elections.

Ashish Ranjan says that while Bihar’s results are evidence, earlier examples also exist where governments overcame anti-incumbency through such schemes and returned to power.

He identifies a pattern among women voters, “Across every state, women form 47–48 per cent of the electorate. When I look at West Bengal, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Jharkhand, and Bihar, the incumbent governments were repeated, and each received around 45–48 per cent of the vote. Now, if 5–10 per cent of this shifts because of DBT schemes, it can easily tilt the game either way. And this became a major factor in Bihar.”

The Bihar Assembly election had a total of 7.43 crore voters, of which men accounted for 52.8 per cent and women 47.1 per cent. The state recorded its highest-ever turnout since 1951, at 66.9 per cent. More significantly, women’s turnout reached a historic 71 per cent—8.2 percentage points higher than the male turnout of 62.8 per cent.

Experts say that this historic level of women’s voting, coupled with the NDA’s landslide victory, suggests that caste barriers were broken in Bihar this time. In other words, women voted for the NDA by rising above caste identities and their caste-backed leaders or parties.

Khushboo Kumari, a 28-year-old resident of Mahadattpur village in Naugachhia block of Bhagalpur, also received 10,000 under the Chief Minister Women Employment Scheme. She used the money to open a tea and biscuit stall. She says, “I voted for Nitish Kumar’s party (Janata Dal United). The 10,000 gave me great support. Nitish Kumar has changed the lives of women like us.”

Experts believe that although a large section of women in Bihar has long supported Nitish Kumar due to his women-centric schemes, the unprecedented turnout of women this time also benefits him significantly.

It is being said that women voters supported the NDA, and following this election, discussions have intensified about Nitish Kumar and his party, Janata Dal United, strengthening their women’s vote bank.

DBTs as the New Incumbency Shield

In the last five years, several states have launched cash/DBT-based schemes targeting women voters just before elections. Interestingly, wherever this strategy was adopted, women’s votes became the decisive factor behind either power retention or a sweeping majority.

Among these, Bihar and Madhya Pradesh stand out, where governments not only returned to power after 20 years of anti-incumbency but did so with historic margins. In Madhya Pradesh, the Ladli Behna scheme increased the BJP’s tally from 109 to 163 seats in 2023. In Bihar, NDA rose from 125 seats in 2020 to 202 seats in 2025. Broad analyses suggest that the massive tilt among women voters formed the foundation of these landslide victories.

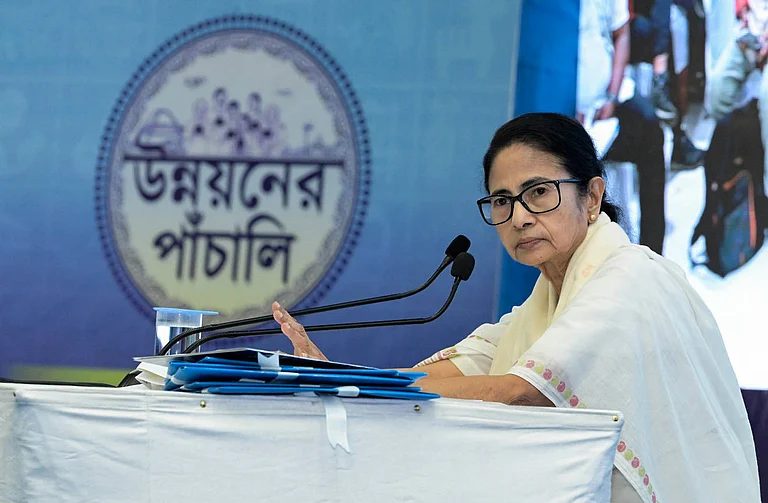

Similarly, Maharashtra’s Mazi Ladki Bahin scheme, launched before the 2024 elections, helped the Mahayuti (NDA) government jump from 161 to 230 seats. In Jharkhand, the Maiya Samman scheme played a key role in reinstating the Hemant Soren-led government. In West Bengal, the Lakshmir Bhandar scheme helped Mamata Banerjee secure a third consecutive term, while in Assam, the Orunodoi scheme proved instrumental in helping the BJP retain power for the second time.

Although ruling and opposition parties alike announce women-centric and DBT-based schemes before elections, the benefits seem to accrue mainly to incumbent governments.

Why? Former Professor at Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai, Pushpendra explains, “Governments constantly face the challenge of overcoming anti-incumbency. When it comes to trust, the public thinks, ‘If the opposition comes to power, they will give it later, but the ruling government is already giving.’ So for women, it becomes easier to trust the party in power, and they gain the advantage.”

Pushpendra further explains, “The groundwork for DBT schemes began with Jan Dhan Yojana. The central government started connecting people to banking for this purpose. Secondly, the BJP-led central government has used DBT in the PM-Kisan Samman Nidhi scheme as well, sending instalments into farmers’ accounts around election periods in various states.”

Most states that overcame anti-incumbency through cash or DBT schemes were governed by the BJP or its allies, though West Bengal under Mamata Banerjee’s TMC and Jharkhand under the Mahagathbandhan are significant exceptions.

A quick look at how and when these governments used DBT as a political tool:

Madhya Pradesh (Ladli Behna Yojana – 2023): Launched in March 2023, giving women 1,000–1,250 per month directly. Implemented eight months before elections and became the centre of BJP’s campaign. Its impact among rural and poor women neutralised anti-incumbency, taking BJP from 109 to 163 seats out of 230.

Maharashtra (Mazi Ladki Bahin – 2024): Introduced in August 2024, offering 1,500 monthly to women aged 21–65. Reached over one crore women just months before the elections. Despite criticism as a “pre-poll bribe,” the scheme yielded massive electoral gains—Mahayuti rose from 161 to 236 seats out of 288.

Jharkhand (Maiya Samman Yojana – 2024): Launched in August 2024, offering 1,100 monthly, later increased to 2,500 right before elections. Its direct impact among rural and Adivasi women helped the JMM-Congress-RJD alliance rise from 47 to 56 seats, and JMM from 30 to 34, despite political turmoil.

Bihar (Mahila Rozgar Yojana – 2025): Launched months before the 2025 election, offering 10,000 immediate assistance and provision for up to 2 lakh in financial support. Opposition termed it “cash distribution before elections” and complained to the Election Commission. Nevertheless, the NDA surged from 125 seats in 2020 to 202 out of 243.

West Bengal (Lakshmir Bhandar – 2021): A key pre-poll promise offering 500–1,000 per month. Although cash was not distributed before elections, the promise itself was immensely popular. TMC rose from 211 to 215 seats, securing a third term despite heavy anti-incumbency.

Assam (Orunodoi – 2021): Begun in 2020, offering 830–1,000 monthly to women heads of households. Used as a central welfare plank in the 2021 election, helping BJP retain power—though without major seat gains—by reducing anti-incumbency.

In all these states, after implementing such schemes, a pattern emerged—despite anti-incumbency, governments not only returned to power but did so with overwhelming majorities. In other words, their vote share rose substantially.

Ashish Ranjan believes such schemes are not healthy for democracy: “Earlier, votes were bought illegally with money and alcohol. Today, votes are being bought legally with cash transfers. Earlier, people chose representation; now they are choosing governments based on payouts. Moreover, governments are becoming less accountable, reducing development to monetary distribution.”

Pushpendra considers this a kind of experiment that began in the last five years, used for the first time across states, and successfully leveraged. However, he believes it will not remain effective in the long term.

The Bihar election marks a turning point in Indian politics, with Direct Benefit Transfer schemes shifting from social support to powerful electoral tools. The unprecedented mobilisation of women voters, breaking caste patterns and strengthening loyalty to the ruling coalition, shows how material benefits can influence voting more effectively than identity-based politics. While these schemes have helped governments across several states overcome anti-incumbency and secure large mandates, experts warn that normalising cash-linked voting risks weakening democratic accountability and reducing governance to transactional exchanges. Whether this model is a temporary phase or the new structure of Indian politics will depend on how long material incentives outweigh demands for real development, dignity, and sustained state performance.