Summary of this article

In Nepal, 35-year-old Balendra Shah goes against deposed PM Khadga Prasad Sharma Oli.

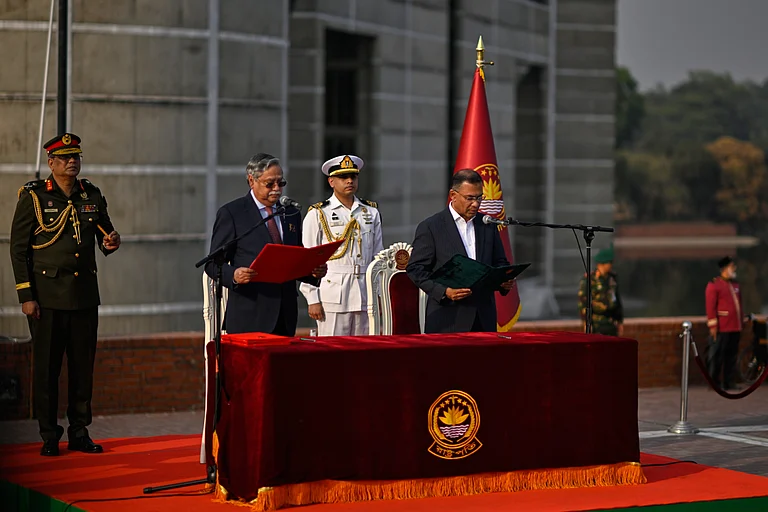

In Bangladesh, the first election since the August 2024 revolt is scheduled to be held on February 12.

The Awami League under deposed PM Sheikh Hasina has been banned from contesting the current election in Bangladesh.

Rapper-turned-politician Balendra Shah has turned the Nepal elections into an Old Guard versus Gen Z battle. Well, almost. The 35-year-old, who resigned as mayor of Kathmandu, the national capital, to contest the election to the House of Representatives, has chosen to take deposed Prime Minister Khadga Prasad Sharma Oli head-on in the 73-year-old’s bastion, Jhapa-5, along the eastern Indo-Nepal border.

The duel between the two prime ministerial candidates rather aptly captures the tone of the election scheduled on March 5—an untimely election necessitated by the ouster of the Oli government in a youth uprising last September.

Oli and Shah are from two political generations. Oli, a three-time prime minister, represents one of the oldest parties, the 1991-born Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist-Leninist) or the CPN (UML). Shah is contesting on the ticket of the four-year-old Rastriya Swatantra Party (RSP). The television presenter-turned-politician Rabi Lamichhane-led RSP emerged as the fourth-largest party in the 2022 election, with a high share of youth voters. More importantly, the RSP gained significant strength with a series of new entrants, including Shah, after the September 2025 rebellion.

While Oli pitches for stability and presents his party as the only reliable, strong national force capable of running the country for a full five-year term, Shah calls for performance-based ‘new politics’ beyond ideological constraints and promises greater authority to provincial bodies to strengthen federalism. The election to Nepal’s House of Representatives involves electing 275 members: 165 through the first-past-the-post (FPTP) system and 110 via proportional representation from party lists.

The contest is not bipolar, though. In most constituencies, it is a four-cornered contest. A third prime ministerial candidate is the 49-year-old Gagan Kumar Thapa of the Nepali Congress (NC), the oldest active party formed in 1950. In a post-uprising generational shift, Thapa has wrested control of the party from the 79-year-old, former five-time Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba through an intense internal struggle against the party’s old guard—literally sending Deuba to retirement.

Two other former prime ministers are contesting for the Nepali Communist Party (NCP). The 71-year-old Pushpa Kamal Dahal, alias Prachanda, and the 72-year-old Madhav Kumar Nepal previously headed the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist Centre) and CPN (Unified Socialist), respectively. To reorganise and revive—in the face of youth discontent against older politicians and parties—these two parties merged in November 2025 to form the Nepali Communist Party (NCP). They have not declared any prime ministerial face, though.

Apart from these four major forces—the CPN(UML), the NC, the NCP and the RSP—several smaller and new parties are in the fray in different pockets of their influence, keeping electoral equations unpredictable in many constituencies.

Whether legacy parties or new formations, all sides remain impacted by the spirit of the Gen Z-led September 2025 uprising by varying degrees. About two-thirds of the previous parliament’s lawmakers are not contesting. With a high share of youth contenders, a strong anti-corruption pitch and widespread calls for change, none of the former prime ministers will find the electoral battle easy.

***

In Bangladesh, where the first election since the August 2024 revolt is scheduled to be held on February 12, the duel is rather straightforward and between two legacy parties and political veterans—the 60-year-old Tarique Rahman-led Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and the 67-year-old Shafiqur Rahman-led Jamaat-e-Islami Bangladesh (JeI).

However, there is a divergence between the two countries in terms of elections.

Since 2008—when Nepal embraced electoral democracy—the country has had 14 prime ministers (including two interim ones), with three years and 88 days being the longest tenure. Fractured mandates, splits and mergers have not given Nepal a stable government in nearly two decades.

In contrast, Bangladesh has not seen a free, fair and participatory election since 2008. Awami League (AL) supremo Sheikh Hasina, who returned to power for a second term through that election, ruled the country till August 2024, when a youth-led protest forced her out of power and the country.

In between, the BNP and the JeI, the two main opposition parties, boycotted the 2013 election, demanding a neutral caretaker government for supervising the polls. The 2018 election was marred by allegations of widespread rigging. The BNP and the JeI boycotted the 2024 elections too. Therefore, both parties have a high share of older leaders as candidates who have not been in power or in parliament for two decades.

The youth force that was at the forefront of the 2024 protests has splintered and shrunk. The new party that a section of them formed, the National Citizen Party (NCP), has joined the JeI-led alliance as a junior partner, contesting in only one-tenth of the country’s total parliamentary seats.

Mahfuz Alam, who was widely believed to be the ‘mastermind’ of the anti-Hasina uprising and served in the Muhammad Yunus-led interim government as a representative of the youth, has himself not joined the new party. Apparently, the party has tilted too much to the right to accommodate centrist Alam anymore. Almost all its women leaders have quit the NCP.

Meanwhile, this election, too, is not an entirely inclusive one. Most senior leaders of the Awami League, including Hasina, are living abroad, predominantly in India, and the party has been banned from contesting the current election.

The contest between the BNP-led centrist-liberal alliance versus the JeI-led right-conservative alliance is broadly taking the shape of one between socio-cultural liberalism and conservatism. The JeI had been the BNP’s junior partner in the 2001-06 government and remained an ally till 2022. However, since the 2024 protests, they have turned into bitter rivals, each hoping to enjoy power on its own.

While the Nepal elections are broadly turning into an old guard versus Gen Z battle, the Bangladesh contest remains between old guards

The JeI is pitching itself as a party that has never come to power. It is targeting the BNP for its leaders’ involvement in corruption and extortion since Hasina’s fall. The BNP hopes to gain from the people’s desire for an improved law and order situation and stability. It also expects an anti-JeI polarisation in its favour.

Apart from the JeI’s role in discrediting the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971, its social conservative and anti-women policies have many Bangladeshi voters worried. Besides, some of the supporters of the banned AL party may also favour the BNP to keep the JeI away from power.

“One crucial difference between the post-uprising election in the two countries is that in Nepal, the forces of the rebellion remain an influential factor in the elections, whereas in Bangladesh, the leading forces of the uprising have gone under the shadow of the older parties,” says Altaf Parvez, a Dhaka-based researcher and commentator on South Asian developments.

Another difference, he points out, is that while the right-wing forces in Nepal have lost much of their voice and appeal since the uprising, the right-wing forces have only grown louder in Bangladesh.

“Since the uprising, the US has gained significant influence in Bangladesh, while India has lost its influence. But in Nepal, India, China and the US—all three forces appear to be in a wait-and-watch mode.” Parvez suspects that while Prachanda enjoys a good rapport with India and Oli with China, the US might like to influence politics through the RSP.

The Nepal Gen Z protest created a political vacuum by exposing the failures of all major traditional parties. However, since the protesters were not part of any organised political force, their energy has been divided, creating multiple new platforms. The RSP has emerged as the main challenger of the old parties this time. It not only gained from the entry of a set of youth leaders like Shah and Sudan Gurung but also from mergers with parties like the Bibeksheel Sajha Party. Like it, most other new parties are governance- and service-centric, rather than ideologically driven.

Among them, there is enthusiasm around the candidates of the two parties formed at the end of 2025—the Kulman Ghising-led Ujyaalo Nepal Party (UNP) and the Harka Raj Rai-led Shram Sanskriti Party (SSP). The Netra Bikram Chand-led Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist), which had been pursuing underground and militant politics until lately, entered the mainstream last year and is in the fray this time. All of them have some pockets of influence. Besides, there is a surge in independent youth candidates. On the other hand, the Rajendra Lingden-led, pro-monarchy Rastriya Prajatantra Party (RPP), which emerged as the fifth-largest party in the 2022 elections, appears to have lost some of its appeal due to calls for change emanating from youth liberal leaders, says a Kathmandu-based journalist.

Since the September 2025 uprising—triggered by a social media ban that was seen as an attempt to stifle dissent—nearly one million voters have been added to the electoral rolls. They are mostly new voters. The voter turnout share among the youth is expected to be high. Good governance, anti-corruption, economic prosperity, job creation, and service delivery—issues amplified by the Gen Z protesters—have gained greater currency in this electoral campaign. Old parties also highlight the question of stability.

While the legacy parties face anti-incumbency, the new parties struggle with rural reach, funding constraints and organisational weaknesses.

In Bangladesh, the JeI vote share is expected to increase significantly, especially due to the political vacuum—the AL and its allies are absent in the polls—and strong anti-India sentiments. The JeI is expected to draw the support of the new voters, mainly due to the current popularity of its student wing on prominent educational campuses. The BNP hopes that an anti-JeI polarisation will give it a landslide victory. The JeI, however, expects that some AL supporters who have faced atrocities and extortion by BNP leaders since Hasina’s exit would vote for JeI to keep the BNP under control.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Snigdhendu Bhattacharya is a journalist, author and researcher

This article appeared in Outlook's February 21 issue titled Seeking Equity which brought together ground reports, analysis and commentary to examine UGC’s recent equity rules and the claims of misuse raised by privileged groups.